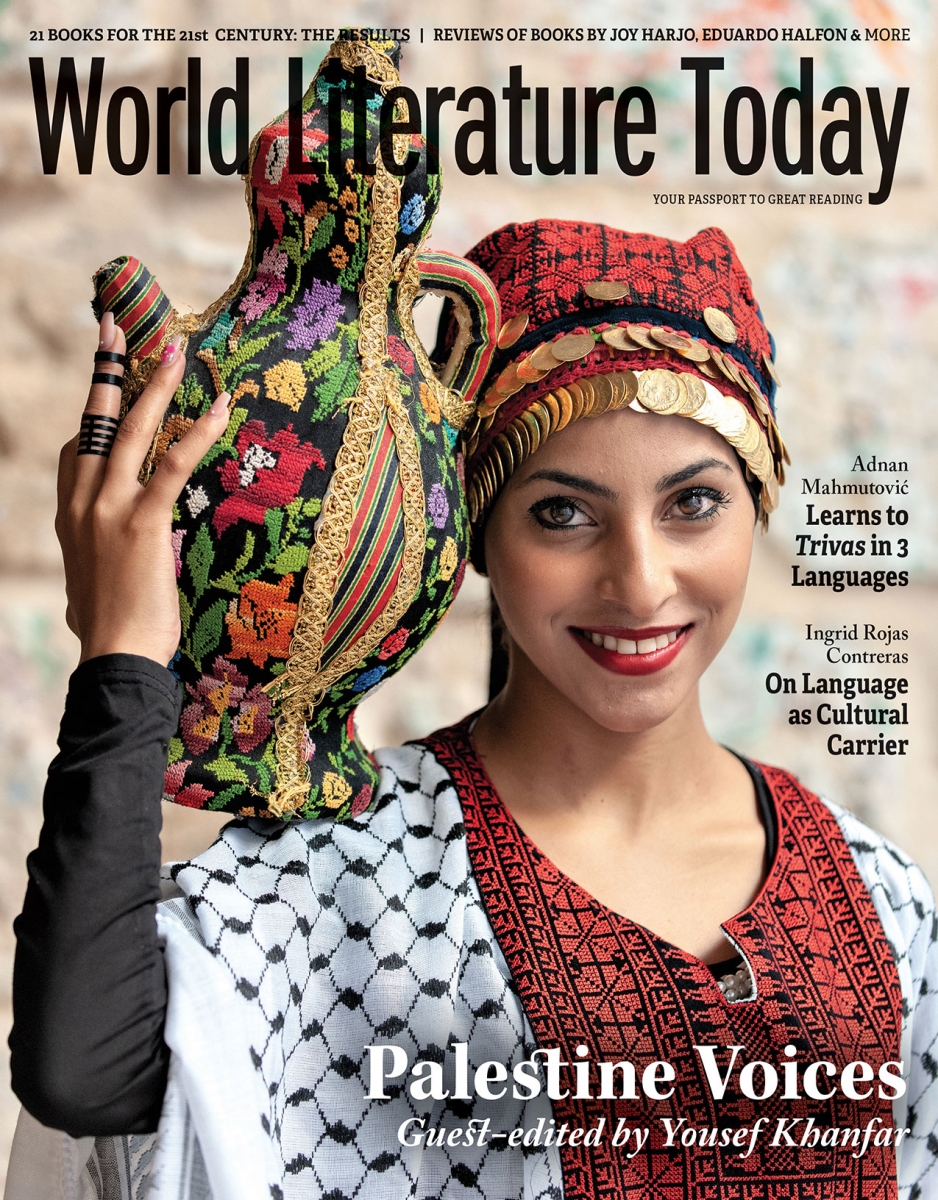

Always More Than a Place: A Conversation about Palestine with Isabella Hammad

I’ve been thinking about literary imprints lately, and how difficult it is to discern the books of one house from another in commercial publishing. Yet I realized that many of my favorite recent books—Aminatta Forna’s The Memory of Love and The Hired Man, Leila Aboulela’s Lyrics Alley and Bird Summons, and Rabih Alameddine’s An Unnecessary Woman, to name a few—have come from one press: Grove Atlantic. It’s true that Grove is a smaller independent outfit. Still, I was pleasantly surprised to feel an aesthetic taking shape in their books, one that is international and unabashedly literary. Now Grove has given us Isabella Hammad’s The Parisian, a book that luxuriates in language and radiates intelligence. It is not a novel that zips along, nor does it tease you with cheap suspense. Instead, it calmly and elegantly, in its own time, unfurls its intricate, beautiful, and timeless story.

Keija Parssinen: I read The Parisian at the start of Ohio’s statewide shutdown, when our understanding of Covid-19 was limited, and panic was in the air. It was a comfort to me to turn to your book at the end of those exhausting, anxious days. The pace of the novel is languorous, which feels like a rare luxury in contemporary fiction. The book meanders in a way I could envision Midhat doing, a kind of flâneur making his leisurely way across the page. How did you approach pacing and time in this book? How hard did you have to fight to preserve that lovely strolling quality?

Isabella Hammad: That’s lovely to hear that it was a comfort. I don’t think I necessarily made a choice to write something languorous per se, but I definitely wanted the readerly experience of time to be long. I wanted to re-create the feeling I’d had as a child where you’re absorbed in a story for a long stretch, and when you reach the end you have feelings of nostalgia for the beginning. I didn’t really have to fight for it. My editors liked the book for what it was and kept it that way. They helped me rearrange a few things and trim some fat, of course.

Parssinen: In the first portion of the novel, when Midhat is in medical school in France and falling in love with a Frenchwoman, he is a kind of familiar romantic hero: purposeful, full of desire, and desired in turn. His character begins to change after he is driven from medical school by an act of anthropological racism. He moves to Paris, embraces a kind of louche bohemianism, and, from that point forward, seems increasingly lost in an ever-complexifying political landscape. Writers tend to talk about a character’s emotional arc, but with Midhat, there’s something more diffuse at work. What did you hope to convey through his journey?

Hammad: It’s true, Midhat does start out like the protagonist of a European bildungsroman, leaving home to define himself as an individual in the world. A bildungsroman usually involves some kind of reconciliation with society and society’s values, though, and in this case that classical narrative is disrupted by Midhat’s awakening to the fact that he is not considered an equal in his environment, in French society; he is not considered an “individual” but rather a type of a person—racially, culturally, religiously. You could say that Midhat initially embraces a model of Western individualism, which he then realizes doesn’t apply to him, because the model of the Western individual is only available to the white European or American.

Then the novel takes on a different kind of storytelling populated by a wider array of perspectives and voices, underpinned by a certain orality or emphasis on the told-ness of the narration, a sense of collectivity behind the story, and a collective audience. Yet Midhat doesn’t quite fit in this new narrative zone either. I’d argue that there is still an emotional arc, though: he struggles to reconcile his French experiences with his life at home in Palestine, and this leads to certain kinds of repressions and performances. But he ultimately achieves an equilibrium by becoming the narrator of his own life and, at the same time, understanding his position in a community, in a collective, in a family and society that accept him for who he is.

Parssinen: The novel opens at the end of the Ottoman Empire; European colonial powers vie for control of the region, sparking a nascent Palestinian independence movement. In another interview, you spoke of being drawn to this time period because you knew very little about it. What did you learn in the writing of The Parisian, and what do you hope readers take away from the book?

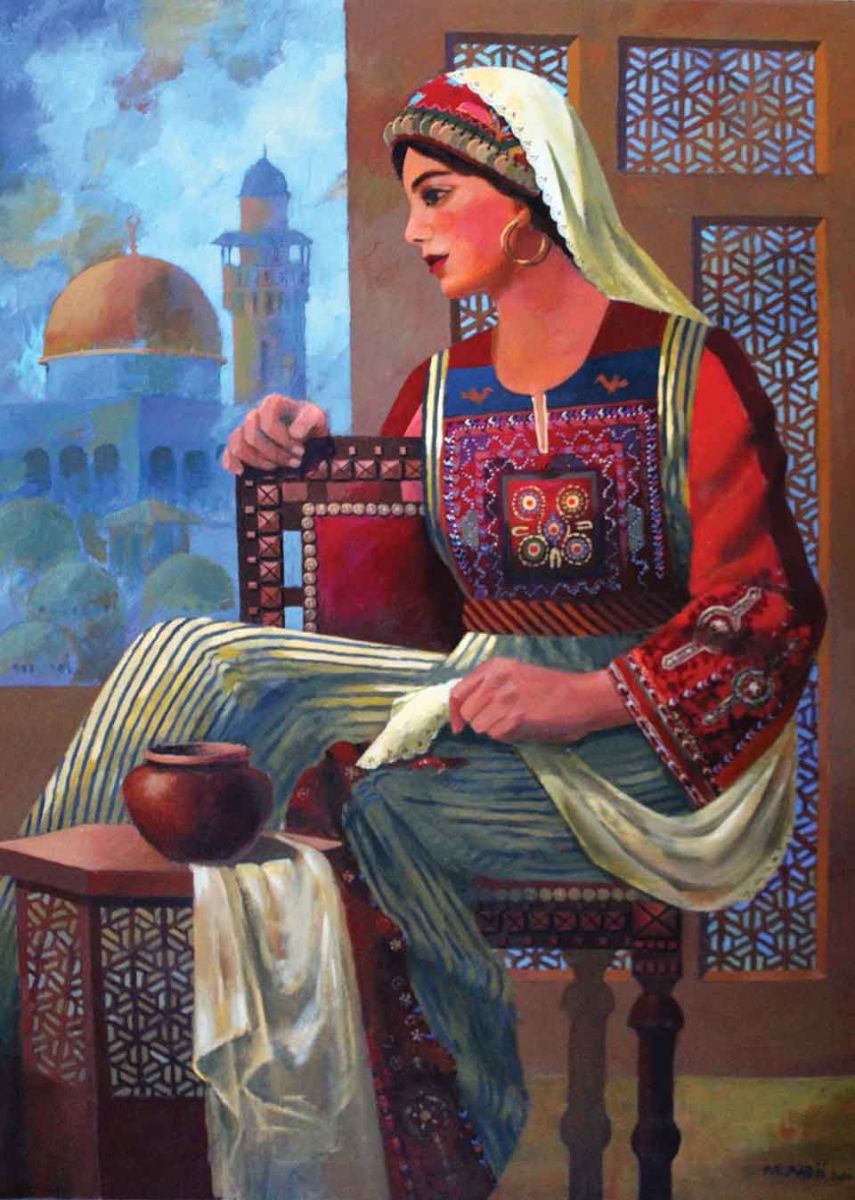

Hammad: I knew the basics. I knew the British ruled Palestine before 1948, and that they had signed it over for the creation of a Jewish homeland in 1917 in the Balfour Declaration, and I knew the photographs and Western-inflected fashions of some of the urban middle and upper classes from that period. But what I learned were the ins and outs of the beginnings of Arab nationalism, which started under the Ottoman Empire and led to the persecution of Arab nationalists who mostly ended up in Paris during the First World War. I also understood the importance of certain class dynamics in Palestinian society and how they fed into the development of the movement, and particularly in Nablus, leading up to the uprising of the 1930s against the British.

But it was also the texture of life in that period that I hankered after, the details, the way things looked and felt and had been built and were thought about. I’m not principally interested in novels as educational materials, or items of political or anthropological interest. I wanted to make a literary experience, not an educational exercise. At the same time, naturally, I was very conscious of the absence of popularly received Palestinian narratives of the events prior to the Nakba, often a result of active silencing of Palestinian voices in mainstream Western contexts, and that was a large part of my motivation for writing the book in the first place. So if it serves an educational purpose in enlightening some readers who, for example, might have fallen victim to the idea that before the state of Israel was created, Palestine was “a land without a people,” then I’ll be happy about that. But I think that in order for such a thing to happen effectively, the book has to succeed as a novel on its own terms, and it must convince the reader aesthetically and emotionally. That’s what I principally hope to have achieved.

I’m not principally interested in novels as educational materials, or items of political or anthropological interest.

Parssinen: Writers have strong opinions about the inclusion of non-English words in English-language texts, often viewing it as an exoticizing practice. Throughout The Parisian, you incorporate many words and phrases in Arabic and French, almost exclusively via dialogue. Talk about the thinking behind that choice.

Hammad: I find it exoticizing when writers italicize non-English words in English-language books in descriptions, so that the words seem to be there purely for “local color” or “local texture.” I find that a bit touristic and depressing. I used the other languages in dialogue, which had to do with the role language plays in the book, in which Midhat cannot translate his life in one language into the other and so experiences a kind of split self. It became clear during the writing process that I would need to include something of those languages or else the whole thing would be too divorced from the texture of Midhat’s experience.

But the way I did it was actually very inflected by the way Arabs often mix English and Arabic in conversation (or French and Arabic), particularly in my family. So it made aural sense to me to transliterate certain words from Arabic, even though it’s not strictly logical or literal and doesn’t map onto actual speech. Even the tools of the most stringent realism are not literal anyway. They are always constructs; mimesis is about persuading the reader something is alive, not about taking an imprint of life. Rather than being exoticizing, I recognize that the inclusion of Arabic words in dialogue can be alienating for a non-Arabic reader. Maybe I also wanted to resist holding the Western reader’s hand, saying “Welcome to the Middle East.”

Parssinen: The title of a Mahmoud Darwish poem asks “Who am I, without exile?” You’ve discussed the ways in which Palestine becomes a kind of imaginary homeland for the people exiled from it. How has the diaspora affected your relationship to that homeland?

Hammad: Mourid Barghouti says the occupation has changed us from the children of Palestine to the children of the idea of Palestine. It’s hard to say how being in diaspora has affected my relationship with Palestine since it’s the only experience of it I have known, but I can say I grew up as a child of the idea, and when I left university I went and developed a personal, physical, and emotional relationship with the place. Right or wrong, Palestine is always more than a place.

Right or wrong, Palestine is always more than a place.

Parssinen: Two important plot points center on the Western gaze as a form of betrayal. The fallout from the first betrayal changes the trajectory of Midhat’s life, and the second betrayal has repercussions for the independence movement. What’s most troubling about both of these instances is that the gaze is generated from people who care a great deal for the person or place in their sights, yet they seemingly cannot help turning them into objects. What goes wrong in these scenarios? In a world where colonialism exists, are human relations doomed to enact those sinister power dynamics?

Hammad: It’s a novel, not a moral tract or a prophetic text or anything except a novel that, among other things, explores the ways that power imbalances affect relationships. Certainly, I wanted to undermine the self-perceived innocence of that gaze, when the gazer thinks they are benevolent. When someone well-meaning seeks to “humanize” another human being, it’s worth investigating why that human being’s humanity should be in question in the first place. The thing is that the macro political and social forces which formulate a colonial situation always seep into personal relations. If you pretend they don’t, you’ll run into trouble. That’s not to say that love can’t exist in such a scenario, since we know it can and does. I also think all relationships across difference involve some objectifying, and romantic love is a good example of that. I don’t think this necessarily needs to be sinister, but you have to be responsible and aware when there’s an imbalance of power. You have to be able to listen, able to admit that you might be wrong, and that your viewpoint is partial, subjective.

Parssinen: In the novel, Nablus confounds the British occupiers; they cannot figure out how to interpret or subdue her. Describe the place of Nablus—the city’s self-image, your experience of it, and how you created it on the page.

Hammad: The story goes that Nablus got the nickname “Mountain of Fire” when Napoleon tried to invade, and the Nablusis set fire to their own fields to ward his army off. I don’t know if that story is true or apocryphal, but Nablus does have a reputation for fighting back. The town is in a valley, and it has a magical air, and a special political and economic history, with particular relationships with Damascus and Jerusalem. I wanted Nablus to be the unspoken “We” of the book, so that even though it’s written in a kind of classical style, it would be underpinned by a logic of oral storytelling. Partly this was a mechanism to keep my imagination in check: it was a way of choosing what material to keep in and what to keep out, by asking, Would someone in Nablus have heard it? Could this story plausibly have reached the ears of someone in Nablus?

Parssinen: Which Palestinian writers, both canonical and contemporary, do you admire?

Hammad: Sahar Khalifeh, Ibrahim Nasrallah, Mahmoud Darwish, Taha Muhammad Ali, Nathalie Handal, Adania Shibli, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Naomi Shihab Nye, I could go on . . .

Parssinen: What is your hope for Palestine now? What future do you envision for the place?

Hammad: I don’t want to talk about hope—but I can talk about dreaming and desire. What do I desire? No more house demolitions, no more separation wall, no more administrative detention, no more withholding Palestinian corpses, no more separate roads for Palestinians and Israelis, no more deliberately complicated bureaucratic procedures, no more making the act of staying where you live an exhausting act of resistance, no more arms deals with America, no more testing out weapons and surveillance technology on Palestinians, no more ideology that perceives Palestinians as a demographic threat, no more “mowing the lawn” in Gaza, no more night raids, no more stealing water and selling it back, no more siege, no more killing unarmed civilians, no more checkpoints, no more, no more. It’s easy to say what you don’t want and harder to say what you do. Let’s start with this: civil and political rights for everyone on the land. My dream is that one day Palestine will no longer be a cause, it will just be a place, where some of us happen to be from, and we could fly into the airport without being interrogated and drive over to Nablus for lunch and then go further up to Akka and swim in the sea . . .

September 2020

Isabella Hammad was born in London. Her novel The Parisian won a 2019 Palestine Book Award, the 2020 Sue Kaufman Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a Betty Trask Award. She was a 2019 National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 Honoree.

Isabella Hammad was born in London. Her novel The Parisian won a 2019 Palestine Book Award, the 2020 Sue Kaufman Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a Betty Trask Award. She was a 2019 National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 Honoree.