“Voices from the Debris Fields”: A Conversation with Carolyn Forché

This three-part interview with Carolyn Forché took place over the course of the past year and a half and was recorded at three different locations: Carolyn’s house in Bethesda, Maryland; in the bistro of the Washington Square Hotel in New York City; and in her office at Georgetown University. (With regard to the addendum that appears at the end of the interview, I emailed Carolyn following the recent election to ask her if she would like to comment on the results. She responded the next day with a timely paragraph.) I had originally hoped that Carolyn and I could complete this interview in one sitting, but we agreed at the conclusion of our first conversation that we needed more time than a single afternoon to do justice to the arc of both her poetry and her career. Consequently, our subsequent interview sessions focused with greater probity on the “main things” of Carolyn’s multifaceted vocation and avocation as a poet, witness, and scholar. Although we didn’t conclude with any sense of final closure, I felt our conversations reached increasingly higher levels of clarity in their exploration of the ideas, poems, essays, books, vicissitudes, failures, and hard-won successes that have distinguished Carolyn’s eminent career.

Part 3: “Voices from the Debris Fields”

Chard deNiord: I’m curious about what Stanley Kunitz might have said to you about your turn away from the lyrical narrative.

Carolyn Forché: You mean after Gathering the Tribes?

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: Because of Stanley’s historical experience and his wariness of ideological, doctrinaire leftist politics and what happened in the thirties: the Hitler/Stalin pact and Stalin’s imposition of a command economy, collectivization, and the Gulag, he was justifiably skeptical and wary. He did not perceive a path that didn’t run straight through that doctrinaire leftism. He liked The Country Between Us, but he also said, “But that’s enough of that now.”

deNiord: He respected your move away from your early first-person aesthetic of lyricized experience and a subjective first-person speaker to a newfound ambition of witnessing disinterestedly to the atrocities in El Salvador? What did he say to you about this?

Forché: He said something like, “You know you cannot be an activist and stay engaged overseas. This is not the life of a poet. And your work must make a turn away from this because it’s a trap, it will destroy you, and it will destroy your work.” I think he was worried that I would become subject-driven and message-driven and that my engagement in human rights and social justice issues would overtake my freedom as an artist. I think he thought that. And that’s certainly fair enough. I understood what he was trying to tell me. I just didn’t follow the advice, partly because I knew at the time that I was still writing as I always had, without preconceptions, without, as Keats would have it, “designs upon the reader.” But Stanley was patient and kind toward me always.

deNiord: Kunitz once remarked in an interview with Mark Wunderlich about poets in America, “To live as a poet in this culture is the aesthetic equivalent of a major political statement.” But I get the sense that he believed in you, despite the political turn you took after Gathering the Tribes.

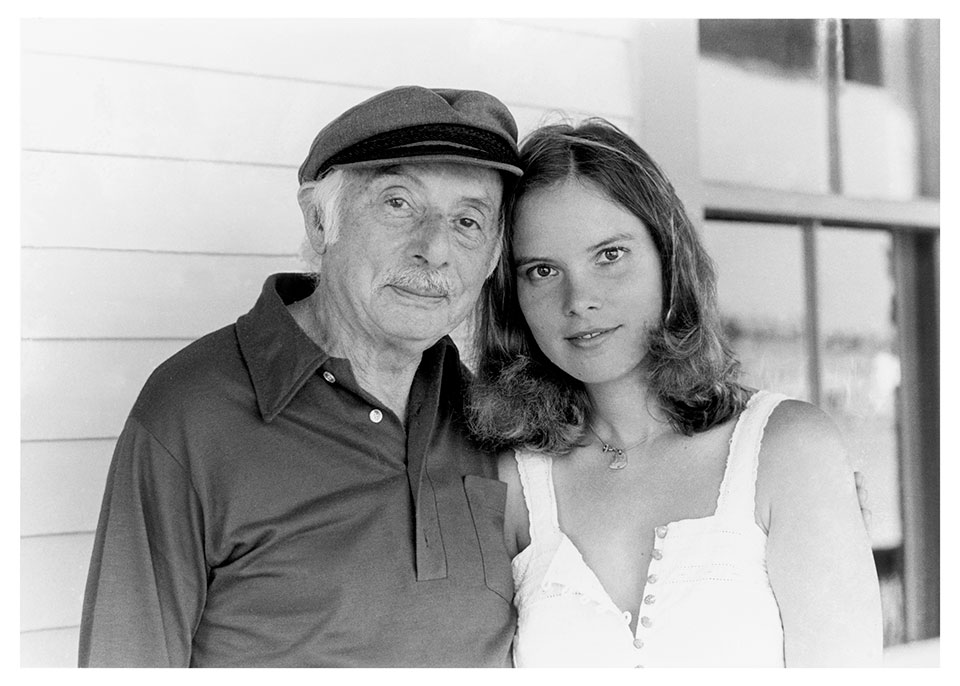

Forché: Yes, we were friends. We spent time together in Oxford, and he knew what he had done for me in choosing me for the Yale Prize. He understood in depth how he had transformed my life. I remember being on one of the London double-decker buses with him—I think we were in London, in fact—and he leaned over and said, “Isn’t it amazing, you know, what happened to your life?” Because he knew where I had grown up and that my father was a tool and die maker. And it’s true, he said, “I bet when you were a little girl you never imagined that you would be riding on one of these double-decker buses through London.” I said, “You’re right, I didn’t.” When we first started corresponding, he asked me about my influences because he was writing an introduction for the Gathering the Tribes book and wanted to know a little bit more about me. I was so naïve and so young. I didn’t understand what he meant by influences. What he had meant, of course, were my poetic influences: who did I read, who had I studied, my formation, he wanted to know about my formation. And I thought he wanted to know about the influences upon my life. So I wrote him about my parents and grandparents and most particularly about Anna, my paternal grandmother who had lived with us when I was young. I talked about that childhood and about a Buddhist monk I had later met in New Mexico. I talked about hiking through the western American wilderness—I was listing all of these as my influences. And they were really the wellsprings for most of the poems in Gathering the Tribes.

He later told me he was amused and touched, and he found my answer endearing because it had nothing to do with poetry or I didn’t mention any poets. So he made do and wrote the introduction using what I had provided. He was very kind. Every Christmas I would visit him for some hours in New York, and I would take him a tin of caviar, he would make a martini for me, and we would talk. He loved his caviar too, but he always put it away. He never opened it. He always put it in the fridge and came back with the martini, so we never shared the caviar. Good for him. It was a gift. I remember the last time I saw him in New York for one of those Christmas meetings, which had become a little bit of a tradition for us. We talked, that last time, about the ultimate dispersal of the human spirit following death. We talked about death, and I asked him what he believed and what he believed would happen after we die.

deNiord: Do you remember what he said?

Forché: Yes. He said: dispersal. Our energy, all of the energy, the molecules that constitute our being, disperse into the universe to be reconstituted in some other way. And he said: “If you think about that deeply it will be a very consoling idea.” And I never forgot this. That became a two-martini meeting because we were talking about death. Anyway, he died not long after that. I asked him about being . . . he was in his late nineties then. “I’m the same as I was at around thirty years of age inside. I’m living in a body that is much, much older, and is worn out, and this is difficult to bear.” “But,” he said, “I want you to know that for the rest of your life you will be yourself. Unless you have Alzheimer’s or something, you will be yourself, and you will always feel somewhat the same age spiritually, mentally, and psychologically, but not physically.”

deNiord: The two of you remained very close until he died in 2006.

Forché: I loved Stanley.

deNiord: His affection for and belief in you transcended any difficulty he might have had following your shift toward a more political muse after your return from El Salvador in the early 1980s.

Forché: He did read The Angel of History. He also believed that I had to turn away from Holocaust writing and meditations of that kind. He felt that I was contemplating—that I was dwelling—too much on history, and particularly the darkest episodes of the history of the twentieth century. And he wanted me somehow to escape from that.

deNiord: Because he must have confronted the same thing.

Forché: He wanted to spare me, I think. But I said that there’s no way out, I have to pass through this. And he understood.

deNiord: And you’re still passing through it.

Forché: He understood. What I really loved doing with Stanley was walking around in England looking at gardens. He loved that too. He knew the names of every shrub, tree, and flower.

deNiord: His garden in Provincetown was famous.

Forché: It was beautiful. He also had an indoor garden on Twelfth Street, a little atrium filled with very special plants. I have never seen such an exquisite indoor garden, in a window that went to the outside. A small conservatory. He knew the names of everything, and almost no one else I have encountered does. He would delight in English gardens, and we would just traipse up and down the streets. It was very difficult to keep up with him. He was already in his late eighties or nineties when we were in England and he could hike up and down hills and look at gardens and never tire. I once asked him what accounted for his longevity—did he have any recommendations? I asked if he thought I should take up running, and he said, “Oh, heavens no. A martini a day is what I believe in.”

deNiord: One and one.

Forché: Well, he always said one for me, but he gave me two the night we talked about death. He was radiantly tranquil and lucid. And, with the martini, almost more impish. His humor expanded a bit. It was wonderful. He seemed to know and to have read everyone, and he would tell wonderful stories about Cal [Robert] Lowell and others. And he didn’t mince words about certain people. Those stories are not to be repeated, but you know if I brought someone up that he didn’t care for, he’d say, “Well, that person did this or that,” and I was always surprised. He wasn’t afraid of voicing his opinions about things. But he was fiercely loyal to the people he loved and believed in. Robert Hass. Louise Glück, who was like his daughter. He had been her mentor, I think. And that might be one reason why, because we had shared Stanley, that Louise has always been so open and generously kind toward me.

deNiord: Such a heartening story to hear about a group of poets’ enduring affection and loyalty toward each other. Certainly not always the case.

Forché: Louise has been really supportive. She defended me in her book of essays, Proofs and Theories, and for that I’m deeply grateful. But she is also scrupulously honest with me. At first she did not like The Angel of History. She did not like it and told me so, or said that she had misgivings, and when she heard me read from it at Williams College, she read it again and wrote me a note that read: “I’ve changed my mind about that book.” I felt taken seriously by her.

* *

deNiord: If I could turn to a historical matter in your two anthologies, Against Forgetting and Poetry of Witness, in which you expound at length in your introductions of each volume, for the first time really in American literature, on the idea of the poetry of witness and extremity in the context primarily of Europe and Latin America. I notice that you don’t discuss those American poets such as Pound, Eliot, and Frost who did travel to Europe in the early twentieth century and then those later on—Robert Bly, James Wright, W. S. Merwin, and Galway Kinnell—who also lived in Europe. There is an arc, broken as it is in places, to that American agon, connecting with international poetry. Like you, these poets also felt they had to become more international.

Forché: And to connect with their peers.

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: Yes. Mostly during the fifties and sixties.

deNiord: Bly included so many important translations of such poets as Machado, Vallejo, Trakl, Neruda, Hesse, and others in his journal The Fifties and then The Sixties.

Forché: And he’s promoting Spanish, and French, and surrealism, and also Scandinavian poetry as if it were surreal.

deNiord: Exactly. He called it “letting the dogs in.”

Forché: Then you have the split. Donald Allen’s anthology and the whole split between the academic poets and the other tributary of the river: what Lowell called “the raw,” the countercurrent of the Beats, Black Mountain, and others.

deNiord: Right, the New American Poetry.

Forché: Yes.

deNiord: Your two anthologies on the poetry of witness, along with your last three books of poetry, The Country Between Us, The Angel of History, and Blue Hour, reflect an international ambition similar to Robert Bly’s, but with a more particular focus on the poetry of witness. You were the first to write about “The Poetry of Witness,” an essay published in American Poetry Review in 1981. Czesław Miłosz published a book entitled The Witness of Poetry in 1984, but you’re really the first poet and critic to categorize a certain kind of poetry written in extremity as “poetry of witness.” It’s a little ironic, I think, given the amount of poems written in extremity throughout Europe and Central America in the past century that an American poet would be the first to identify and then anthologize the best of these poems, and then, in your second volume with Duncan Wu, expand your project to include poems of witness from the entire tradition of English poetry. It’s fascinating that the poetry of witness was conceived by a young American woman in the late 1980s following more than a century of poets writing “poems of witness” without calling them that or anything else with a political or religious connotation to distinguish them from other kinds of poetry. Do you think poets outside of America have an aversion to labeling poetry written in extremity, as well as other kinds of poetry, such as feminist poetry, confessional poetry, beat poetry, etc.?

Forché: I’m not sure there’s an aversion to labeling in other traditions, if we mean by that the formation and coalescing of schools and movements. I can think of several—the Misty poets of China, who wrote in resistance to the Cultural Revolution; in Germany, twentieth-century expressionism, “New Objectivity,” and Dada, then something pejoratively called “Trümmerliteratur” or “rubble literature,” written in the West in the aftermath of the war out of the misery of life as it was then. In the East, there was “Social Realism.” Interestingly, in the 1970s when US poets were avoiding anything that might be regarded as political, the Germans were also turning inward with a movement called the “New Subjectivity.” Ingeborg Bachmann, the prose writer Peter Handke. The “New Subjectivity” didn’t take over everything. There were also Enzensberger, Grass, and Böll. After the Berlin wall came down and the Stasi files were opened, there emerged an East German group called Prenzlauer Berg poets after the Berlin neighborhood where they lived. It was later discovered that they had been informers to the Stasi.

There are also other examples: “The Hungry generation” in West Bengal (poets who revolted against colonialism), and “The New Apocalyptics” in 1940s Britain, who resisted political realism. I don’t know of any school or movement that explicitly defines itself in relation to the experience of extremity. I suspect that “rubble literature” was more a dismissive critical response than a proclamation of identity. For me, poetry of witness does not announce a school, movement, or species of poetry. It is simply a way of reading works that perhaps might be dismissed as “political” in a narrow sense, particularly in the United States during the late twentieth century.

deNiord: Have you encountered any criticism about signifying poetry written in extremity as poetry of witness in Europe or Latin America?

Forché: There seems to be great interest in the thought of witness, in this mode of reading and consideration. I have found this particularly true in Mexico, Armenia, Vietnam, England, Libya, Finland, Sweden, Zimbabwe, South Africa—mostly places where I have had opportunity to discuss these ideas.

deNiord: The arc of American poets’ agon over the past century has been such a start-and-stop affair, from Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot’s post–World War I poetry and essays to Robert Bly “letting the dogs in,” as he liked to refer to his inclusion of Latin American poets and European modernists in his journal The Fifties and The Sixties, to Charles Simic and Mark Strand’s beautiful anthology, Another Republic (1976), to your first anthology, Against Forgetting (1993), to J. D. McClatchy’s Vintage Book of Contemporary World Poetry (1996), to Ilya Kaminsky and Susan Harris’s Ecco Anthology of International Poetry (2010), and finally to your most recent anthology, Poetry of Witness: The Tradition in English, 1500–2001 (2014). How exactly do you see your anthologies and poems as an integral link in this arc of American poets’ desultory struggle over the past century to connect internationally, particularly in your focus on the poetry of witness?

Forché: Bly was devoted to translation, and rightly so, as we had translated so little up to that point and neglected most of the rest of the world. I really think that the nadir of this was during the 1950s in the aftermath of HUAC and at the height of the Cold War. From about 1948 to 1961 when those first translations began to appear—that period was somewhat introspective and quite xenophobic, and there’s another factor: we were triumphant after the Second World War, and we saw ourselves as the center of the world and certainly the reigning world power. Ours was the default ideology. In other words, what we perceived mattered in a way that the perceptions of the rest of the world did not.

deNiord: Yes, exactly, and sort of the incipient notion of American exceptionalism, although it wasn’t called that then.

Forché: When you think about what happened in the 1960s, which really didn’t happen until the late 1960s, following the Civil Rights Movement, and the antiwar movement of the late 1960s and the ’70s, what did the establishment fear? They feared the political engagement of the 1930s. They had no other model for this than Stalinism. US citizens in opposition could not be other than “fellow travelers.”

deNiord: Right. In the book by Eric Bennett I mention above, Workshops of Empire, he chronicles the history of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, particularly in light of the pedagogy that Paul Engle developed at the workshop in response to the communist threat of downplaying the role of the individual in the creation of “complex” literature. The University of Iowa has publicized it as a testimony to the idea that “vivid renderings of personal experience would preserve the liberal democratic soul—a soul menaced by the gathering leftwing totalitarianism of the USSR and the memory of fascism in Italy and Germany.”

Forché: As I mentioned, my colleague at Georgetown wrote a book on that same subject, and there’s new information now being studied about US government manipulation of literary culture, which might suggest that literature has been taken far more seriously than might be supposed.

deNiord: Like luring the Eastern European intelligentsia away from behind the Iron Curtain.

Forché: They were manipulating and funding literary magazines, promoting certain literary careers as opposed to others. They operated within the US, too, in a manner that was actually illegal at the time. The Congress for Cultural Freedom, funded by the CIA, had offices through the world, funding symposia, magazines, and scholarly endeavors. The organization also mounted campaigns against individuals—Pablo Neruda is one example. The magazines included Encounter in the UK, Quadrant in Australia, Quest in India, and Forvm in Austria. There were many others, some which at that time accepted money without clear expectation, such as Partisan Review and Kenyon Review. The CIA itself considered this intervention “its most daring and effective Cold War instrument.” There are books to recommend on this subject, in addition to Rubin’s, including Frances Stonor Saunders’s The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters.

deNiord: Averell Harriman and the CIA supported Paul Engle with a small donation of $10,000.

Forché: So that was still happening by the time we reached the possibility of intervention in Central America.

deNiord: And in a way that affected pedagogy in MFA programs as well.

Forché: It was not only politics that they opposed but political engagement of any kind and, by extension, interest in the rest of the world, unless the objective was literary translation of certain acceptable poets and authors.

deNiord: So this literary reaction formation to the communist threat was absolutely fascinating. It created a pedagogy that championed the Emersonian ideal of “man on the farm” or “man thinking,” as opposed to the mere “farmer” or anonymous worker. In literary terms, the heroic writer. Paul Engle was actually fired from the MFA program he founded at Iowa, known as the Writers’ Workshop, only to then found the International Writing Program, which has had even more of an international impact. Writers such as Mo Yan, Bei Dao, Etgar Keret, Dubravka Ugrešić, and Janusz Głowacki are among its alumni.

Forché: The domestic Iowa Writers’ Workshop was the mother ship for the other programs, which replicated its ideology until quite recently, and this still holds at many programs. Not all, of course. But there are faculties that still counsel students to avoid politics.

deNiord: This goes back to the early days of the CIA when it was called the National Security Act in the early 1940s.

Forché: When I went back to research the biographies of all possible poets to include in Against Forgetting, I began to notice patterns. These sent me back to the library, to the files, and to the newspapers, further and further until I found the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the other government efforts toward cultural intervention and control, and I thought, “Wait a minute, there’s much more going on here than I had imagined,” and so then, years later, when I had found out about the committee within the intelligence agencies formed to monitor, undermine, counter, and oppose journalists and others involved with Central America, it wasn’t as surprising to me. Disturbing, unnerving, but not surprising.

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: You need to read Rubin’s book for one piece of this.

deNiord: Do you mean in the US?

Forché: No, in Africa, and elsewhere. In the US they didn’t really have to do very much. The periodicals once funded by the Congress for Cultural Freedom have distanced themselves, folded, or disavowed this support since then. But historically there’s plenty of research that’s been brought to light. When I began to wonder why I was being accused of being “political,” when I didn’t feel myself to be, in the strictest sense, “political,” as I hadn’t joined a group or affiliated with a party, I began to sense that something else was behind the accusation, a strong current, an undertow. Rather than argue about the relation between politics and poetry, or the poet and the state, I decided that it might be wiser to open another space for this discussion, one that had to do with ethics and morality and the social space of conscience, the dissemination of information, the fifth estate, and so on. There was a space for debate and argument and a viable and thriving critical culture, so I thought to propose this rather than argue in Cold War, Manichean terms.

Rather than argue about the relation between politics and poetry, or the poet and the state, I decided that it might be wiser to open another space for this discussion, one that had to do with ethics and morality and the social space of conscience, the dissemination of information, the fifth estate, and so on.

I would propose an alternative. I didn’t feel particularly drawn toward political engagement, as I understood it. I bristled at the censorship—what I considered censorship—of art, censorship of poetry, censorship of testimonial writing, and the impulse to tell poets what to write about and what not to write about. This went against everything I believed about art in a free republic. “Witness” was initially misread as just another way of talking about politics. I didn’t want to have that argument, but rather to talk about the validity of this other space. Probably I should’ve had the argument, but I didn’t feel up to it at the time. I never defended myself and never answered the attacks on the concept of the poetry of witness. As for interference by the intelligence agencies in our literary culture, well, that is a matter of record, and now must be confronted and taken into account in any understanding of the postwar period.

deNiord: Well, it’s fascinating, isn’t it? How it affected the pedagogy of creative writing programs.

Forché: I think that it affected the fiction—the prose—more than poetry. I could be wrong.

deNiord: Eric Bennett discusses writers who were celebrated during the Cold War, particularly Hemingway and Dos Passos.

Forché: Dos Passos wasn’t celebrated; he was buried. So, too, any writer whose work seemed to have a political dimension—and who was celebrated? A number of others. The pedagogy leaned toward producing a form of low-mimetic realism. This whole notion of “writing what you know” was interpreted to mean that one must write exclusively or primarily from within the sphere of American domestic life.

deNiord: Yes, there was a stealth agenda.

Forché: And if you do situate your writing in, God forbid, another country, you do so as the location of personal drama. One writes from the position of a visitor, or a tourist, but not from any other position. The place served as backdrop for the unfolding of something deeply personal, the breakup of a marriage, perhaps, or a search for identity.

deNiord: Right. So this kind of pedagogy must have inhibited the readership of a few giants like Milan Kundera who were writing behind the Iron Curtain for a long time.

Forché: To the degree that these writers were dissidents, they were considered acceptable and even interesting. Kundera was not a dissident and never claimed to be. Brodsky was a dissident. Miłosz was, after a time, a dissident, but he also had been a diplomat for Communist Poland.

deNiord: And so there was this delay.

Forché: The dissidents received substantial and quiet support, and they were embraced and accorded academic and critical legitimacy.

deNiord: Especially the Russian poets.

Forché: Especially the Russians. But there was a lot of literature that never got published.

deNiord: That you, in fact, actually published in Against Forgetting.

Forché: Well, for example, Wisława Szymborska. She was not known nor embraced here at that time, nor really was Zbigniew Herbert. I don’t think that Szymborska’s books were available here when Against Forgetting appeared. I wasn’t looking for politically acceptable writers. I was looking for who was there.

deNiord: And who had been censored.

Forché: Yes, and who was there and had suffered in certain ways. When you go to Poland, as I went to Poland fairly soon after the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Bloc, there were writers who weren’t forgiven or accepted because they had not openly been dissidents. There’s a stage when a sort of cleansing goes on, a test of political purity, and you dare not ask to consider the times they lived through and their situations. Perhaps they weren’t, in fact, political, perhaps they were having their—

deNiord: Well, sometimes they were just trying to survive.

Forché: Well, you know what happens with reputation and readership. It’s partly the work itself, of course, but it is also a question of who promotes the works and how much, who translates it, and who has the power to make it visible in the English-speaking world and beyond.

deNiord: And that’s what you’ve done in your anthologies.

Forché: For some of them, yes, but it was heartbreaking to leave people out, because I knew that if I could include them, there would be a chance that other people would discover them, so there’s a little bit more life for their work. But those I had to leave out—they’re going back into the deep library of oblivion, and someone else will have to rescue them in the future. I had to edit the anthology to one-quarter of what I had assembled for that volume. There are three-quarters left, in various boxes in my house.

deNiord: You’ve talked about this, the cost of the book.

Forché: That’s right, and they didn’t want—they couldn’t sell it at a higher price.

deNiord: It ended up being twice the size you had proposed originally, and they did sell it.

Forché: They did sell it. They told me something funny, since it’s still in print twenty-three years later. Dear beautiful Carol Houck Smith, who was its editor at Norton, told me that she was “afraid that it isn’t going to stay in print, it’s not going to sell.” I said, “I’m not doing it for that reason, but I do think it will because poets have long shelf lives. I said you don’t just go out and buy the latest poet. If this book is valuable, they will keep reading it.” She was used to editing fiction, where, apparently, the new matters.

deNiord: Yes. But then she started editing books of poetry, too.

Forché: She did, but she knew how to sell and promote fiction, and so she thought my book had to meet some of those same requirements.

* *

deNiord: Well, this is interesting in light of your own work because in Blue Hour, for instance, you give yourself over to the selfless voice of the other in which the earth itself witnesses to oppression and injustice. You’re channeling, but it’s interesting what you said about the poets you had to put back into the drawer. It’s as if you’re saying, well, there is a kind of uber-witnessing.

Forché: The figure of the angel Metatron, the archangel in Judaism known as the “Recording Angel.”

deNiord: So we have to resign ourselves to the Earth itself witnessing to hidden or forgotten injustices.

Forché: The Earth takes us all back one way or another. We stay here, dispersing here, and the earth itself will disperse.

deNiord: And that involves a kind of faith in a way, but I don’t want to call it religious necessarily. What would you call it?

Forché: It’s a faith in meaning, in the sufficiency of life itself. And the dispersal that we will experience is a dispersal that our earth will experience, our sun, our planetary system, and our galaxy. Everything is unique and once. Unique and once. One can mourn that but also celebrate it. I wanted to say something about the Recording Angel, the Metatron, who appears in The Angel of History. I didn’t name the Metatron in that work but instead simply referred to it as “the recording angel.” The celestial scribe.

Wim Wenders broke this figure into individual human-like angels in his film, Wings of Desire. He had them especially interested in libraries—these angels in their long dark coats would stand in the libraries, looking over the shoulders of those who were bent in study over books. They also rode trains and subway cars, and they would simply listen, much of the time feeling sad while overhearing human thought. They liked libraries, I think, because they could listen to the thoughts of those who were reading human thoughts in books: the testimony of human life itself, for which the libraries serve as repositories. All those books standing, binding to binding in the dust waiting.

deNiord: What are they waiting for?

Forché: They’re waiting for the opening of the book. Edmond Jabès talks about this in a very beautiful way. And writing in that way, the sacred becomes a way of preserving—

deNiord: And that idea seems to infuse a lot of your recent poetry.

Forché: It gives me hope. It merges my sense of the spiritual with my sense of art. I absorb writings of others and I write myself, recording and opening. Jabès works with two figures: the reading of the book and the writing. If you’ve read his four-volume Book of Questions—there are other books, but that is where one would begin, and then The Book of Margins, The Little Book of Unsuspected Subversion, The Book of Shares. Rosmarie Waldrop is his translator and best interlocutor and an extraordinary poet herself. I also recommend Questioning Edmond Jabès, both the title of the book and the act itself.

Witness is the legibility of the mark of extremity and the wounding and the passing through fire.

deNiord: Like the Elvis Costello song, “Everyday I Write the Book.”

Forché: That’s right. And Emmanuel Levinas. If you think about his work, and Buber’s I/ thou, and you think about Levinas’s idea of our infinite and inexhaustible responsibility for the other—what if the other is encountered in the book?—in words, in language: witness is the legibility of the mark of extremity and the wounding and the passing through fire. It’s legible in the book, saved in the book, and the Levinasian responsibility to the other is the responsibility of the reader to the book and to what is read and known there. Do you see what I mean?

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: So that is how this all fits together, although it isn’t something that I have been able to articulate in one place.

deNiord: Well, I think that’s what’s waiting. I mean it’s the natural culmination in many ways of these two volumes.

Forché: You have seen the Q&A I did with Christian Wiman in Poetry magazine, right?

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: He asked questions that began helping me tease this out. He’s asked me to speak at Yale in the fall. Maybe this is what I should write, speak . . .

deNiord: I think that it’s a natural next step in your thinking.

Forché: I have to go to Yale in a couple of weeks—this is more stressful because it’s for an annual lecture before an international human rights symposium.

deNiord: So you are going to the Divinity School and the Law School?

Forché: Yes. This is the Law School and it’s for human rights, from the point of view of international human rights—law at the intersection of other disciplines, this year particularly in the arts.

deNiord: Does this make sense?

Forché: Yes! It does. But it’s a bit daunting. The reason I withdrew a bit from the poetry world, why I backed off the whole discussion of how literature and poetry were suppressed and manipulated by political powers in the US—I didn’t want to engage it. I was fearful, I think, that I would be dismissed or, worse, vilified. I have witnessed attacks upon scholars in the academy. Such attacks are difficult to counter because they mask as something else.

deNiord: What does it mask as?

Forché: Disinterested scholarly or critical appraisal.

deNiord: It’s interesting—how the idea of New Criticism figures into this.

Forché: Well, then you have to go back to the Agrarians, how and when they were formed, how they were promoted and rewarded, the masters of the beautiful art of close reading.

deNiord: I’m glad you brought that up because it also has to do with the fugitive poets who were Agrarian. They figure into this very profoundly.

Forché: I admire and practice the art of close reading and teach it to my students. But if it’s done in order to isolate the literary work from its context, for example, in political engagement, then the practice has itself been politicized and deployed against the freedom of art. To the degree that this was an instrument of that endeavor, I reject New Criticism while embracing the practice of close reading. When I entered the MFA world, I have to say that, especially when I briefly taught at the University of Arkansas, there was considerable commitment to the New Criticism.

deNiord: There’s a detached purity to it that’s appealing to the New Critics for its emphasis on the ultimate expendability of the author in his or her creation of literature, as Eliot argues in his famous essay, “Tradition and the Individual Talent.”

Forché: You don’t have to consider anything other than the text on the page. It’s self-enclosed, self-referential. The focus is entirely upon the organic unity of the poem severed from the hand that wrote and the time in which the poet lived. From the surroundings. New Historicism arose to counteract that, most notably in the work of Stephen Greenblatt. And I think Poetry of Witness, to some extent, that is why it was resented: for reinscribing the importance of the life and the historical context, that we look at the life and the experience. I think it’s a wonderful practice to read closely and then to understand something of the life and the times, and, if possible, to tease out the trace or mark of that experience.

deNiord: I think your example of Miklós Radnóti is a very powerful response.

Forché: What is one going to do with that? One can read closely in Hungarian, can think about the complexities of the translation, but if one doesn’t know where those eclogues came from—

deNiord: It doesn’t matter that he was buried for six months?

Forché: No, it doesn’t matter that he was forced to march, it doesn’t matter that he was one of twenty-two survivors out of two thousand—and so who can ignore those things? And forget that Paul Celan was a poet who lived through the Holocaust. This doesn’t matter? That seems to me absurd.

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: I remember reading an essay in the New York Review of Books by Helen Vendler, a very thoughtful essay on Czesław Miłosz, and I think that she became aware that he was, in this work, taking into account his life and times, but she seemed to insist that, in his case, it was different: this is Poland. In other words, the political concerns and commitments and decisions matter if you are from Poland, but also seeming to suggest that we, as US citizens, weren’t supposed to have such concerns or commitments. We were supposed to remain unaware of the larger world and also of our own country’s crimes and complicities.

deNiord: And this is where you’ve suffered.

Forché: Well, you know I don’t worry about—

deNiord: I know you don’t. But what the backlash did to you.

Forché: The backlash came from somewhere. It had a gestation and a formation. As Trump supporters didn’t come from nowhere, it was something cultivated, yes. And you can take the pieces and assemble them. The confessional poets emerged in a period of great interest in psychoanalysis and examination of the mind, and that was a nice distraction to have during the 1950s

deNiord: The evolution from the Agrarian and the New Critical to the confessional was inevitable.

Forché: Yes, and it all worked well. And in a way, the generation that published translations around 1961—Strand, Bly, Wright, Merwin—all published translations almost simultaneously. They threw a spanner into the works a bit. There was resistance to these poets at first, not as a group, but individually.

deNiord: Because?

Forché: Because they had translated poets from other countries and all at once. They also had broken with formal, academic poetry and begun writing free verse. They had broken with the past and all at once. They were all lions, of course, as well as Adrienne Rich, who didn’t translate but who also broke with the academic formalists.

deNiord: Well, she was writing poems about Elvira Shatayev, the Russian climber who died on Lenin Peak.

Forché: Yes. With that subject matter, she also departed from the expectations of academic formalists. These poets went in search of another poetry. They went in search of poetry from other countries and for a reason. There was frustration. There was a pent-up sense of a rigid lack of possibility.

deNiord: There seems to be a long-term resentment that Europeans harbor toward the American MFA culture.

Forché: The Europeans understand the political dimensions of the manipulation, but I think they also feel there’s a measure of legitimacy to this, that American writing is oblivious to the rest of the world and could be accused of solipsism.

deNiord: That’s an easy generalization to make, but you just mentioned seven giants who—

Forché: Who rebelled against it? Yes. But you asked about MFA culture, not literary culture. I think the Europeans, and some others, perceive the former as suffering from that deliberate resistance to social awareness we spoke about earlier. But there are extraordinary moments, in literary culture, of resistance: Charles Simic and Mark Strand and their anthology, Another Republic: 17 European and South American Writers.

deNiord: Great book.

Forché: A brilliant anthology—a precursor for me.

deNiord: Where did one go just twenty-five years ago to read Francis Ponge or Carlos Drummond de Andrade or Yehuda Amichai or Yannis Ritsos?

Forché: We didn’t have a substantial international anthology in print at that time. When I taught at the University of Arkansas, I developed a course called “World Poetry.” That was really controversial at the time. My colleagues, all men, really resented this course and spoke against it, even though Miller Williams was himself committed to translation. So the initial gathering of poems that became Against Forgetting were from the “World Poetry” class at the University of Arkansas. And why? Only because I couldn’t find any books that had contemporary works in translation. There were no anthologies. Eventually, I thought I should make an anthology that I can use in class because I kept photocopying poems. I can’t keep doing this, I can’t. I had to feed dimes in the copy machine. They changed the “fair use” laws, and such copying became problematic.

My mother had seven children, all born within ten years of each other. My mother would always call out to us, “Would somebody answer that door? Somebody pick up the baby? Somebody?” And I was standing at the copy machine and one day said to myself, “I wish somebody would make an anthology so I wouldn’t have to do this anymore.” And I heard my mother: “Would somebody please be somebody?”

I had this big phonebook-sized photocopied stack of poems, and I was invited to take the ID badge of somebody else to go into the American Booksellers Association convention, held in DC that year. And someone was in town, I can’t remember who it was, who said, “Why don’t you come with me?” Someone else couldn’t make it, and I could wear her badge. I had the anthology with me for some weird reason, and I ran into a man I had known in the El Salvador anti-intervention network. I was shocked to see him in the American Booksellers convention. He asked how I was, what I was doing, and if I had another book coming out. This was well after The Country Between Us. I said no, no other book, I can’t write poetry right now.

But I didn’t want to say I wasn’t doing anything. So I told him that I was editing an anthology of poets in translation from various parts of the world. He thought it might be something that his company might be interested in. As it turned out, he was now the sales manager for W.W. Norton. He took my contact information and said, “I’ll be in touch.” And then about a week or two later he wrote and said, “Come up to New York, I have arranged a meeting, and we’ll talk about your project.” I took the train to New York and went to the Norton offices. There was a young receptionist who greeted me with, “Oh yes, yes, Ms. Forché sit down, and we’ll be right with you. Would you like some coffee?” and I answered “Yes, I would love some coffee.” She reminded me that we had ten minutes before my presentation starts.

deNiord: You didn’t know that you had to make a presentation? The guy didn’t tell you?

Forché: Well, no, he didn’t. I said, “Presentation? I didn’t know about a presentation.” And she said, “It’s going to be in the board room with the senior editors . . .” I told her that I hadn’t known this, and didn’t have a presentation. And she said, “What do you take in your coffee?” I told her I took milk. She disappeared and never returned. I’m led into the room with all these men and one woman, Carol Houck Smith, and I thought: I’m dead, I don’t have a presentation, what am I going to do? The nuns always trained us to confess, so I said, “Ladies and gentlemen, I didn’t realize that I was expected to give a presentation, and I don’t have one, so I thought what I would do is speak extemporaneously about this project and then I could answer your questions.” I talked for about half an hour.

There was this silence, they were listening, and an older man raised his hand and he said, “Ms. Forché, what exactly is a poet of witness? And how is one different, for example, from Robert Frost?” And I thought, Uh-oh. Probably this doesn’t make any sense. I offered to tell them a story about one of the poets that I included, and I told the Radnóti story. There was silence, and one of the younger men asked how long it would take me to finish. I answered, perhaps foolishly, “A year!” One year, I thought, I could do it in a year. “Oh, really?” they said. I said yes. They asked more questions, and then I left. A week later I had a contract to deliver the anthology in a year. And of course I had no idea how to procure permissions. I didn’t even know where most of the poems came from because I had photocopied them randomly from library books. I didn’t have the citations regarding who had published them or translated them. I had to start over from the beginning.

deNiord: How did you manage to gather all these poems together?

Forché: It took three years. A friend living in Minnesota offered to write for the permissions. She became the angel of permissions. Andrea Gilats.

deNiord: Then you got some help, right?

Forché: People started sending me poetry and recommendations. But I didn’t really have any help. Daniel Simko and I did a lot of the work together—

deNiord: And Peter helped you also.

Forché: Yes, Peter Balakian and also David Kaufmann and others. I asked advice from many poets and translators, but the publishers would not allow me, for financial reasons, to commission new translations. I was limited to already published, available translations. I was asked to write an introduction, headnotes for each of the sections, and of course biographical notes. I also decided to include a selected bibliography. The publisher required me to have my headnotes vetted by historians, so we did that. All of them came back approved. It was quite a task: World War II in two pages. But the challenge for me was very real. I had, for example, written a section on the Middle East, and hoped to write in such a way that my own sentiments would not be apparent. The happiest moment I had was when both Israelis and Palestinians responded that they liked their headnote and thought I saw things from their respective points of view.

deNiord: Is that when you got to know Mahmoud Darwish?

Forché: No, I got to know him later. I had admired him but didn’t know him yet. I got to know him through the editor Munir Akash and his wife, Amira El-Zein, a poet, scholar, and translator. Perhaps you know them?

deNiord: No.

Forché: He is the Syrian editor and publisher of Jusoor, an Arabic literature journal.

deNiord: Did you get to know Yehuda Amichai?

Forché: Yes, I knew him from when he was teaching at NYU, and he also brought me to Israel in the mid-nineties to read at a festival in Jerusalem that he organized.

deNiord: So just a huge amount happened afterward, after this came out.

Forché: After The Country Between Us came out, a lot happened. After Norton contracted to publish Against Forgetting, the work took another three years. It came out in 1993. So it took from 1981, when The Country Between Us was published, until 1990 to gather the poems and decide to make an anthology.

deNiord: It was really a teaching tool more than anything else.

Forché: All of us used to photocopy a lot, in those days. It was about sharing work with students and getting them to read in translation, or at least to read outside American literature. I just wanted them [the students] to know more. And I also wondered why they weren’t reading Tomas Tranströmer, and other important poets from other traditions, the living and the dead.

* *

deNiord: What’s interesting, as far as your own experiences, is that you wrote poems in El Salvador that were poems of witness, and so you must have identified with other poets—in other words, you weren’t approaching this from purely an academic—

Forché: It was when my work was attacked by other poets, and there were more than a few such attacks, that I began to look toward the work of others. It was a bit like developing a disease and needing to find out how others had coped with it. And the only way I could find out was to discover other poets who had gone through wars and later written poetry. Most of the poets I found were from other countries.

deNiord: Strangely, you were criticized by several of your American colleagues and fellow poets for doing this.

Forché: Yes, that’s true. There was some praise and interest, and there were some lovely things that happened, especially when I began to realize that some readers of The Country Between Us weren’t poets, and that was gratifying. I received letters from people from many walks of life, also from people in prison. I accumulated a trunkful of poetry books, mostly translations, in my car, those I had with me when I visited Terrence Des Pres. We started thinking about our question, your original question, which concerned education, and the political formation, the formation of consciousness, within the academy.

With respect to the formation of writers and poets, much has been said about undergraduate and graduate programs in creative writing. There is much that is positive that needs be said. Before the great democratization of higher education made possible by the GI Bill, most people couldn’t go to college. Before the proliferation of MFAs, most people couldn’t become writers. So that, I think, is a very positive thing. And I think there are many ways of looking at the “elephant” of MFA programs from different points of view, including the political. Some of the criticism comes from an elitist, reactionary position. Some of the criticism is legitimate and concerns the pedagogical inheritance from Iowa: the depoliticized writer and poet, the apolitical poet. So are we coming back to something? I don’t know.

deNiord: Well, back to Terrence just for a second.

Forché: Okay.

deNiord: You know, his belief in sharing painful experiences radicalizes the poet. I think in a transformative way. Returning him to an emphasis on community rather than individual ego.

Forché: Terrence had a tendency to view things in an interesting way.

deNiord: In what way?

Forché: He tended to generalize from particular instances. He hoped that the confrontation with evil would radicalize and activate the empathic imagination. However, in some people this confrontation does not have that outcome. You see, he used the term “human” (to make us more human) as a positive term.

deNiord: And that word “community” becomes very interesting as far as the figurative community, the literary community, the community. And so he started examining what that community is.

Forché: What is it? Or what does it mean to say to become more “human,” because humans are capable of horrible things and that is true of all of us. He always valorized the term. And I always wanted to ask him about this, but I didn’t have the language to ask him, and then he died. I formulated the question after his death. I’ve never been able to interrogate that because—you know what I’m talking about—Terrence was my mentor, but I did introduce him to poets from other traditions. He wrote his dissertation on Shelley, but he hadn’t read a lot of contemporary poetry. He had known Mona Van Duyn at Washington University, and he also knew Helen Vendler at Harvard when he was in the Society of Fellows, so he had some contacts with people who were poets or who wrote about poetry. But he didn’t really read that much of it—if you looked at his shelves, there wasn’t. And then he opened up and just began to devour that work. This became his project after The Survivor.

I think, in a certain way, he set me on the track of the anthology as well. We always talked about these poets, and he’d come up with a beautiful essay and publish it somewhere; eventually these essays became his next book. I think that our conversations led him to Praises and Dispraises and me to Against Forgetting. And the notion of witness evolved in part from our conversations about bearing witness. I remember telling him that I thought that many poems could be read as “witness,” and he suggested that I think about it. We talked our way toward this. I tell my students, it’s not a thing, “poetry of witness,” I made it up. You can’t go around talking about it like you talk about Romanticism or something.

deNiord: Whitman has this wonderful sentence, “The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it.” Which isn’t really Romantic—

Forché: In Whitman’s case, we definitely have absorbed him.

deNiord: Thinking of all the schools of poetry today, all the backlash you have experienced, of the small readership of poetry now, 6 percent of the public reads poetry and literary fiction—

Forché: Six percent? That seems high to me.

deNiord: I know that seems high.

Forché: I mean, just over 2 percent of Americans are in the prison system. And 6 percent read poetry!

deNiord: There’s a larger community, it seems to me, that transcends what Whitman’s talking about here.

Forché: He lived in a time of formation of nation-states and the birth of a republic. And now we live in a time when we must become a world community. If we are to survive, we writers must go in the direction of creating a world community of poets or a world republic of letters. It doesn’t have to do anymore with nation-states or with national identities.

Now we live in a time when we must become a world community. If we are to survive, we writers must go in the direction of creating a world community of poets or a world republic of letters.

To return to Mahmoud Darwish for a moment: Munir wanted me to collaborate on a translation he and Amira were making. They sent Mahmoud some of my books, and he told them he wanted me to do the English, to make these English poems. He said, “My translations have been frustrating for me in the past because they’re accurate from the Arabic, but they’re not yet poems in English.” So he asked me if I would do it, and we spent the summer translating Unfortunately, It Was Paradise. It was a spectacular summer, and then I met Mahmoud when he came to the States to read one magnificent evening at Swarthmore College, an evening that included an introduction by Edward Said and music by Marcel Khalife, the Lebanese master of the oud.

Men and women came from all over the eastern seaboard. They were all in there, in hijab, without hijab. And when Marcel, who had set some of Mahmoud’s poetry to music, started to play one of those pieces, the whole auditorium erupted, singing along in Arabic and from memory. It sounded like a choir from heaven. It was late April, and my fifty-third birthday, as I remember, and Mahmoud later took us all to a steak house for a birthday celebration. This is among my most cherished memories.

deNiord: Well, you know, Carolyn, you must feel, at this point, embraced by the world. More so than by your own country.

Forché: I’ve been very lucky.

deNiord: Don’t you feel that?

Forché: I do.

deNiord: And what you said about living in Paris for the first time, being in Paris that year: you said you love the Parisians and the French because they didn’t care if a poet had been published or not. A poet was a poet.

Forché: If you said you were a poet, the first question they asked was not, “Oh, have you published?”

deNiord: They were just interested in what you were thinking.

Forché: Or they would say, “Oh, I’d love to read your poems!”

deNiord: Which is so un-American.

Forché: I feel badly that Americans feel that they have somehow to prove themselves.

deNiord: That really is counter to your whole project in many ways, right? I mean like those poems in Radnóti’s pocket.

Forché: He wrote them hoping that someday, somewhere, someone might read them. It was like Celan’s message in a bottle: somewhere, someday, on the shores of the heart.

deNiord: So those are the interesting, earthly books we were talking about. Where they exist on earth.

Forché: I miss Mahmoud Darwish and Czesław Miłosz and Tomaž Šalamun and Tomas Tranströmer, all of them gone now. I feel incredibly fortunate to have known these poets, and that I was able to meet Wisława Szymborska. I have a book signed by her, and I treasure it. I feel blessed. My goodness, it makes up for, well, I don’t need things to be made up for. You know what? It teaches you things, it tests you, and that’s fine. Most people on earth go through horrible experiences. Humans suffer and starve. What I feel about those times now, those years, is simply a kind of curiosity, a desire to know, as we were discussing earlier. Why the thinking was what it was. And how that has changed, and I think it has changed profoundly, not only since 9/11 but because of the aftermath wars, the endless wars we have prosecuted following that attack.

deNiord: But we’d be mistaken in thinking any of these voices will save us.

Forché: No, such saving is always radically uncertain.

deNiord: So yes, radically uncertain, and yet there is nonetheless a noble purpose and cause in preserving these voices at the same time. As well as extrapolating them into snowflakes.

Forché: And if you think about Whitman, he was writing about our period. He thought he was writing about the birth of a republic in the contiguous, continental states. He thought he was looking at the birth of a nation. And because he was praising the multitudes, all who had gathered from all around the world and their great numbers, he really was present with regards to time. He saw our century, too, and the birth of humanity.

deNiord: And then once you realize that was true . . .

Forché: Then it doesn’t matter.

deNiord: It doesn’t matter. And that is a great—what was it? You put words to it . . .

Forché: Well, you’re free, which Stanley Kunitz always believed. The other thing that I think was good was that it all happened to me when I was very young. I was thirty-one when The Country Between Us was published, so I was impressionable enough. I got that part over with early.

deNiord: Well, many never get beyond their need for fame.

Forché: Fame is evanescent. You are yourself, regardless of whether you are “known” by a multitude of others.

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: You have to walk around in your body. That does not change. But I think that being “known” by people you don’t know is a very difficult experience.

deNiord: In the sense, being known by people you don’t know—

Forché: Yes, because of the level of exposure. You’re exposed and you can easily develop a false sense of selfhood and of reality that doesn’t correspond to actual reality. The world is no longer reflected back to you undistorted. Poets mostly never have to worry about this because they are almost never that famous in the larger world.

deNiord: There are a few delusional people who think that it does matter.

Forché: To provide some context on what does and does not matter: my husband took this photograph [opens to a photograph in El Salvador: Work of Thirty Photographers]. He was in a vehicle on a road in El Salvador, and he saw figures moving up ahead. And they were moving around on the road, so he slowed down, and he decided he wanted to see who it was and what was happening. He stopped the car, parked it, got out of the car, and walked toward the figures, and he saw that they—he showed them his camera, put his hands up, they were military—and he saw that there were bodies in the road and that the soldiers had machetes. He put his hands up and walked slowly, slowly, toward them taking pictures, and they saw that he was taking pictures. It was a period in the war when the military was proud. They stood and posed behind each of those corpses, and he took the last picture with them standing behind the corpses, as if actually wanting to be photographed. And then he got in the car and drove slowly off. But this is the picture he took, and they had just mutilated the bodies. They were soldiers—soldiers who became, in this image, anonymously and briefly famous.

deNiord: They had guns, too.

Forché: Yes, but they used the machetes to cut the bodies up.

deNiord: It’s like the colonel being proud of the ears.

Forché: That’s right. Harry [Mattison] was working for Time then, but this photograph was published in Newsweek. And they captioned it: “Soldiers on Macabre Guard Duty.” So the soldiers were presented as simply “guarding.”

deNiord: But they did do it.

Forché: Yes. They were doing it as Harry encountered them.

deNiord: So the US—

Forché: Newsweek changed the caption to “Macabre Guard Duty,” and Harry said that’s when he realized—

deNiord: What was going on.

Forché: But this was very difficult. When I look at these pictures now, they look as if they were taken in the far past, in another time [turns another page of the book]. Those are the guerillas. Look at them. They’re just kids here. They’re poor. They rose up and fought and died years ago. Knowing them changed everything for me.

deNiord: And you were there, at that time.

Forché: Yes, I left just before the war was thought to have officially begun. I was there during the time of the death squads.

deNiord: And you saw a lot of that.

Forché: Corpses, yes. Many. But the war itself, meaning the military engagement between the US-supported Salvadoran military forces and the guerillas, mostly happened after I left. I was never in the fighting. I witnessed the death squads’ brutalities and butchery. I didn’t see the fighting. But I did go back when the fighting was over and the truce was made.

deNiord: So this gets back to my point that you weren’t interested in the poetry of witness—

Forché: No, that idea hadn’t been born yet.

deNiord: Right, right. But it was instilled in you, it was born in you as a result of your own firsthand experience before you even began writing about it. As opposed to reading a news story or hearing about it.

Forché: In the beginning, I was translating a woman poet.

deNiord: Claribel Alegría.

Forché: Who was deeply affected by things she had witnessed as a child, and I had to work through that in her poetry, and I became—

deNiord: In El Salvador, right?

Forché: Yes. But something happened.

deNiord: Something happened. You know that’s interesting, because you know how the book The Prophets always talks about “something happened.” For a prophet to be a prophet, Heschel talks about this in his two books, that one of the key things he mentions is that something happened.

Forché: You can’t say what.

deNiord: Exactly, but that something happened to you.

Forché: It’s an explosive moment, and it turns you in another direction.

deNiord: For the rest of your life.

Forché: Yes. You can’t go back. I didn’t know that at the time, but I would choose it again.

deNiord: Something happened to Amos, something happened to Hosea, something happened to Isaiah.

Forché: And you can never go back. I’m calling the memoir What You Have Heard Is True, the first sentence of “The Colonel” poem. It has an epigraph from James Baldwin: “For the strangest people in the world are those people recognized, beneath one’s senses, by one’s soul—the people, utterly indispensable for one’s journey.” Leonel is that person for me. My book is not about the war itself, but about what happened before the war.

* *

deNiord: You were a good friend of Daniel Berrigan, who recently died. You both come from a Catholic background and had intense discussions about witnessing and other matters. Could you talk a little about the nature of your friendship as well as some of the ongoing conversations you had with him? Do you think your religious background as a Catholic ended up having a strong influence on you as a poet who has followed in the prophetic tradition of witnessing, as Berrigan did?

Forché: I think the answer is yes, my poetry is influenced by the crucible of Catholic formation. My friendship with Daniel began upon my return from El Salvador, when I was involved with the antiwar, anti-intervention, sanctuary, and witness for peace movements. Daniel was also deeply committed to this work, and our paths sometimes crossed. We had long conversations and one recurring argument concerning the right of the oppressed to defend themselves and overthrow their oppressors by force after all peaceful means have been exhausted. Daniel, the radical pacifist, did not support the use of violence under any circumstances. In the immediate aftermath of my experience in El Salvador, I was persuaded of the right of the oppressed to armed revolution under certain conditions. Now, I no longer believe that change comes about through force of arms. I wish I hadn’t wasted what time I had with Daniel on this particular argument. The rest of the time we talked about the theology of liberation, poetry, and other such worthy subjects. We taught a few workshops together, one in a monastery in upstate New York, presenting poetry of witness. He was an extraordinary human being, a dedicated and deeply spiritual priest. It is a great honor to have known him.

deNiord: In your various interviews you show a familiarity with a large number of philosophers and critics like Emmanuel Levinas, Walter Benjamin, Jean-François Lyotard, Hannah Arendt, and Hans Magnus Enzensberger—to name just some of the them. Are these authors ones you’ve largely read on your own? Leaving aside Benjamin, whose presence in The Angel of History is clear, how important are these writers for understanding your work?

Forché: As an undergraduate, I studied existential phenomenology, but since then I have read largely on my own, often guided by friends with scholarly expertise in continental philosophy and twentieth-century European thought. We’ve talked about some of them: Sandor Goodhart, Geoffrey Hartman, Tony Brinkley.

deNiord: Near the end of your 2000 interview with David Wright, you comment: “Poetry is what maintains our capacity for contemplation and difficulty. Poetry is where that contemplation and difficulty converses with itself. Poetry is a very important endeavor. It’s so important, it’s so sacred a practice that the way in which it’s been commodified is an angering problem for me. I don’t want it to be that way. I’ll continue to write it out of joy and longing to do so.” How would you modify, augment, or intensify that comment today, some sixteen years later?

Forché: I still believe that writing and reading poetry and other forms of serious literary art preserve our capacity for meditative attention and contemplation; I still believe strongly in the necessity of poetry, of imaginative art. I would no longer say that poetry has been “commodified,” and I’m not sure what I meant by that at the time. I have always considered poetry to be an artistic practice that most resisted commodification.

I still believe that writing and reading poetry and other forms of serious literary art preserve our capacity for meditative attention and contemplation; I still believe strongly in the necessity of poetry, of imaginative art.

deNiord: Besides people like Terence Diggory, are there any other critics whose work you value? Whether of your own poetry or of that of other poets you admire?

Forché: Calvin Bedient, Robert Boyers, James Longenbach, Dan Chiasson, Juliana Spahr, David Orr, Alicia Ostriker, and others.

deNiord: Besides Ilya Kaminsky, what other living poets’ work do you admire, find compelling, moving?

Forché: There are many, and may I be forgiven for omitting? I think I would like to mention some younger poets, if I may, such as Ishion Hutchinson, Tarfia Faizullah, Jericho Brown, Jamaal May, Natalie Diaz, Sherwin Bitsui, Don Mee Choi, Valzhyna Mort, Tracy K. Smith, Mai Der Vang, Nikola Madzirov—

deNiord: You have written and said so many memorable things about the poetry of witness over the years, I would like to conclude by asking you to respond briefly to a few questions about some of your most incisive comments and insights with regard to your maturation from a lyrical poet at the start of your career to a poet of witness who has sacrificed her subjective muse for a more selfless voice that, in your own words, “lays open to the other [in] an unending address, a call to the other, which manifests that-which-happened.” I’d like to start with this provocative quote you made several years ago: “One can say I’m political but not say I’m ethical? I remember the poet June Jordan once said to me, ‘I don’t know what my politics are, but I know what I want to help have happen.’ I always liked that phrase.” What’s more appealing to you specifically about saying “I know what I want to help have happen” than talking about your politics?

Forché: I lean toward ethics rather than politics, toward intersubjective awareness, the practice and cultivation of imaginative empathy, a sense of interdependence within the biosphere.

I lean toward ethics rather than politics, toward intersubjective awareness, the practice and cultivation of imaginative empathy, a sense of interdependence within the biosphere.

deNiord: You have often quoted this claim about language by Paul Celan: “One thing remained attainable, close and unlost amidst all the losses: language. Language was not lost, in spite of all that happened. But it had to go through its own responselessness, go through horrible silences, go through the thousand darknesses of death-bringing speech.” Now that you have edited two large volumes of the poetry of witness, Against Forgetting and The Poetry of Witness: The Tradition in English, 1500–2001, could you talk a little about just what it is about “language” that survives extremity? Just how poetry finds the last word within the “horrible silences” and “thousand darknesses”? Are there any poets in particular in either of your anthologies that you feel address this mystery directly?

Forché: Czesław Miłosz acknowledges that in some poets, a peculiar fusion of the personal and historical appears, and in such poets, we may also observe a certain reticence; they are poets of silence as much as of the word; they have deeply assimilated personal and collective experience and have surrendered themselves to the work of poetic transmission. They are often perceived as hermetic and obscure while imagining themselves to be striving for utmost clarity. If I had to choose two poets who most exemplify this fusion, they would be Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann.

deNiord: You write this trenchant definition of the poetry of witness in your essay “Reading the Living Archives: The Witness of Literary Art”:

Witness, then, is neither martyrdom nor the saying of a juridical truth, but the owning of one’s infinite responsibility for the other one (l’autrui). It is not to be mistaken for politicized confessionalism. The confessional is the mode of the subjective, and the representational that of the objective. . . . In the poetry of witness, the poem makes present to us the experience of the other, the poem is the experience, rather than a symbolic representation. When we read the poem as witness, we are marked by it and become ourselves witnesses to what it has made present before us. Language incises the page, wounding it with testimonial presence, and the reader is marked by encounter with that presence. Witness begets witness. The text we read becomes a living archive.

Your idea of the text becoming a “living archive” posits language with a sacred function, but not necessarily in the religious sense. William Blake wrote that the “most sublime act is to set another before you,” which gets at your notion of “humans coming into being through relation.” Where do you draw the line in your thinking, if you do draw a line, between the religious and human connotations of the poetry of witness as a “living archive” that wounds “with testimonial presence”?

Forché: There is a certain sacred radiance to the language of witness. After all, the term itself, witness, derives from the Greek μάρτυρας (mártyras). In my own apprehension, both sacred and secular connotations are available; the language suggests constellations of thought and awareness, human and divine.

deNiord: Would you mind elaborating a bit more on this quote, especially what you mean by “poem as trace, poem as evidence”? It seems like a poem of witness in your description of it here takes on a metaphysical validity all of its own, one that must involve both the poet’s sovereign imagination and the reader’s faith in the poem. “By situating poetry in this social space, we can avoid some of our residual prejudices. A poem that calls us from the other side of a situation of extremity cannot be judged by simplistic notions of ‘accuracy’ or ‘truth to life.’ It will have to be judged, as Ludwig Wittgenstein said of confession, by its consequences, not by our ability to verify its truth. In fact, the poem might be our only evidence that an event has occurred: it exists for us as the sole trace of an occurrence. As such, there is nothing for us to base the poem on, no independent account that will tell us whether or not we can see a given text as being ‘objectively’ true. Poem as trace, poem as evidence.”

Forché: Language here is regarded not as representational but as evidentiary; the word is indexical, pointing toward that which happened. One is moved or marked by the poem in the act of reading: by the vortices of the imagery, metaphorical resonances, metonymic play, by the music, the compression of utterance. Language written in the aftermath of extremity bears the imprint of that experience, regardless of its content; it is that which is written out of that which was endured. In many respects, this is ineffable. The words come not from recollection in tranquility but from wanderings in a debris field.

Language written in the aftermath of extremity bears the imprint of that experience, regardless of its content; it is that which is written out of that which was endured. In many respects, this is ineffable. The words come not from recollection in tranquility but from wanderings in a debris field.

* *

Editorial note: The following addendum was added in November 2016.

deNiord: The country is reeling in the wake of the recent election. What are your thoughts?

Forché: In times like these, and from what I know of the world, one must marshal inner strength, must be courageous and resolute, calm and vigilant, must connect with others of like mind, must not compromise with racism, bigotry, and hatred but must also be quietly prepared for the consequences of every confrontation (physical harm, imprisonment, death). Must do so, anyway. Must go to every length to protect others. Not many humans can do this. Many will live as many lived in Eastern Europe and in Russia under totalitarianism. They will mind their own business, get what they can to survive, and go about their daily lives. That’s all right for them. We should not be judgmental of them. But there were dissidents too, and they worked together, and after decades of work, the system came down.

In this moment, because of environmental death, because the next five years so matter (are crucial to human survival), we do not have “decades.” Harry and I have lived in countries under oppressive regimes, with governments supported by the US. We have not often been the good guys. Most people in the US paid no attention to this. They lived their lives. While all this was going on, while the wars were going on, they had fun, studied, worked, had kids, took the boat out on weekends. But in those countries, people suffered greatly, disappeared by the tens of thousands, were tortured and mutilated, and still people fought back. They lived in clandestinity. I knew some of them. They saw the world clearly. They found a peace within themselves. A friend said to me once: “I don’t fear death. When I made my commitment, I was already in the grave.”

We are going, now, to wait. We’re going to be courageous and resolute, stoic and clear-eyed. We’re going to watch carefully and keep our intuition on high alert. We’ll know what steps to take when the time comes. I believe that the president-elect will sit in the White House and everything will be done by others, most especially the legislators. They will change some laws, but he will not be able to deliver on his promises to the people who elected him. There will come a time when his supporters will realize that they have been betrayed. Then we’ll see. Those are my thoughts this morning.

May 2016

Carolyn Forché’s first volume, Gathering the Tribes, was followed by The Country Between Us, The Angel of History, and Blue Hour. Her latest collection, In the Lateness of the World, is forthcoming. Nelson Mandela praised her international anthology, Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness (1993), as “a blow against tyranny, against prejudice, against injustice.” In 1998 she received the Edita & Ira Morris Hiroshima Foundation for Peace & Culture Award for her human rights advocacy and the preservation of memory and culture. She holds a University Professorship at Georgetown University, where she directs Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice. She is currently at work on a memoir.

Editorial note: For more, read part 1 and part 2 of this interview, plus five of Forché’s previously unpublished poems.