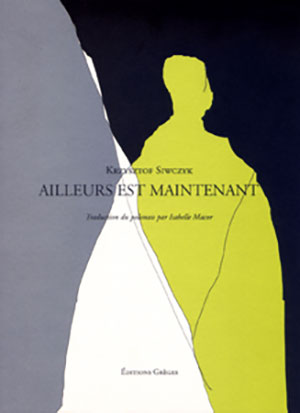

Ailleurs est maintenant by Krzysztof Siwczyk

Paris. Éditions Grèges. 2015. 108 pages.

Paris. Éditions Grèges. 2015. 108 pages.

“Poetry, including the poetry I write, is of no use, no help to anyone. It is theodicy without an object, communion without lips. It is a pure parlance of obviation.” This citation, with which the poet welcomes his readers in the online magazine Versopolis, introduces us to a leader of the young generation of Polish poets. Having grown up in the 1980s and lived through the political and media revolutions of the 1990s, Krzysztof Siwczyk has published twelve volumes of poetry. In 2014 he won his fourth literary prize, the prestigious Kościelski

Prize reserved to poets under forty years of age. He has played in several movies, is an experienced literary magazine editor, and directs the the Mikołowski Institute of Rafał Wojaczek in Silesia. His work has yet to appear in English, although it has been exhibited through the “poetry in the metro” movement in several world capitals since 2011.

Proceeding from Czesław Miłosz and Tomas Tranströmer, Siwczyk skips from philosophical to prosaic considerations and coins a disjointed, anonymous, amorphous, unrecognizable world: “The elevated generalization of specificity / much lowered his sensitivity to neighbors. / Uniformity happily prevailed. The material / from which he will create the shape of a face, / fills streets and buildings, suitable for / anything except destiny, / for it seems that there is no reason to laugh” (“Konkrety”). Worn smooth by linguistic experiments, his pebble of a language expresses a pell-mell of perceptions jotted down in a nonlinear, anecdotal way. The poems are filled with cultural references, such as his surrealistic imagery of melding the natural and human worlds. Linking metaphysical and colloquial reality and broadly referencing history and post-technological culture, Siwczyk writes poems as lemmas in which the soul longs for meaning.

Highlighting beauty through its absence is one of the techniques of Siwczyk’s antipoems. Visiting Europe’s most ancient settlement, unesco’s World Heritage city of Ohrid, the poet writes a long vanitas in which he “awaits a clearing . . . A moving fluorescence appearing on the horizon, / Yet evading a snapshot’s capture like a sentence whose topic / Remained unspecified until it expired” (“Ochryd”).

The translator of Ailleurs est maintenant, Siwczyk’s first volume in French, explains that this poetry is not easy or attractive. Indeed, it requires the reader to listen to the poet’s voice, to its sounds and rhythms; only then does understanding rise from the words effortlessly, sketching the awesome structure of a work constantly under construction. Isabelle Macor’s translation highlights the narrative elements of the poems and draws them toward their prose dimension.

She chose approximately one-third of the contents of the Polish volume published in 2011 under the title Gdzie indziej jest teraz. Ailleurs est maintenant is not bilingual. The absence of a table of contents sends the reader into free-fall enchantment.

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin