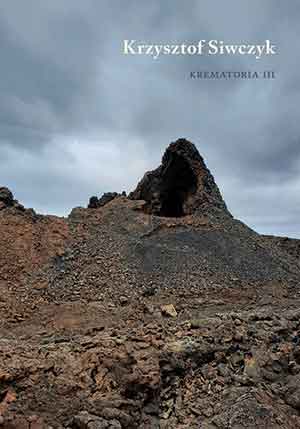

Krematoria III by Krzysztof Siwczyk

Kraków. Editions Austeria. 2022. 68 pages.

Kraków. Editions Austeria. 2022. 68 pages.

KRZYSZTOF SIWCZYK IS known for his philosophical poetry that yields long lines reasoning out the malaise of adulting, the problematics of identity in a world of gray indifference. Debuting at age eighteen with Dzikie dzieci (Wild children), which received the 1995 “Czas Kultury” Prize, Siwczyk wrote eight more volumes of poetry between 1999 and 2012. He is currently deputy director of the Mikołów Institute, where he edits the literary journal Arkadia. Dokąd bądź (Where to now), which earned him the 2014 Kościelski Prize, was followed by Jasnopis (Jasnopis; 2016) and Mediany (Medians; 2018). In 2022 UNESCO placed a plaque bearing his name on a park bench in Cracow, and volumes of his poetry appeared in in Artur Becker’s German translation (Auf nächtlicher Reise. Gedichte, Parasitenpresse) and in Julian Birbrajer’s Swedish translation (Klarskrift och andra Dikter, Prosak Förlag).

Devoted to a dynamic language that defies genres, Siwczyk most recently produced a Holocaust-based trilogy. The first volume, Krematoria I. Krematoria II, was a finalist for the 2022 Wisława Szymborska and won the Silesius Prize in the Book of the Year category. The second volume, Krematoria III, reinforces a minimalist, almost aphoristic style. “A Verse Backward,” the shortest poem of that volume, is a one-liner: “You alone occupied a whole verse and my life.” Enjambments shorten lines, as in “Social Poetry (engagée)” where the word engagée defines the first verse, “To let everyone know /. . . / That she came to become the world.” As a movie actor, poet, essayist, and performance participant, Siwczyk uses key moments, which he calls illuminations, to convey a larger meaning. As in calligraphy, a circuitous underground process of connecting semantic meaning and memories accompanies the long apprenticeship of choreographing thought and verse. Thus teased to the surface, words emerge in rapid, terse, and precise bursts.

In Krematoria III, the self-perpetuating, somewhat logorrheic language of reflection has evolved, freeing the verses from thought encumbrances; the sparse, permanent black signs on the white page invite the watermarks of connection. The central signifier is the word Crematoria, spelled with an ominous capital letter. It inflects unstable realities and uncertain destinies that “Burn without a big halo / Like us / They only hiss and spit fire / Although the world long ago / Stopped caring about them” (“Shrubs”). The characters’ melancholy and aimlessness appear to be caused by the grief of Poland’s national traumas of World War II, the Holocaust, Soviet occupation, and the end of the Cold War. With the lesser wounds more difficult to define, the Holocaust serves as a gauge of terrible clarity: “War / Holocaust / Reduction to a stick / Secam / Soap / Faint” (“From Current Histories”). The last poem, “Peak Achievement,” exhorts the reader to “Return to Crematoria / Like to oneself.”

Holocaust-related raw, memorializing bursts reverberate and amplify the present. In “Nowhere to No One,” a dying person’s “buried shoes in boxes” are modeled after a “previous life.” Death is “the echo of a hub like the inner valves / Of a heart that no longer beats” (“Degrees”). The dead return on sidewalks of night, mute, scattering at dawn through the ethereal fence of a train platform (“Ashes”). Dead children placed “In a Corner” return to ask “Where else / What now.” Whether through medical and technical terms or a more poetic tone, these poems create a phenomenology of suffering. Redemption is hard: Mother “extracts feces and love from father / Hard as coal they end their half-century / Together in heavy dreams that enable him / To emerge” (“Extraction”). Grief expressed so concisely announces a new direction for a poet who has been called the most important poet of the 1970 generation.

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin