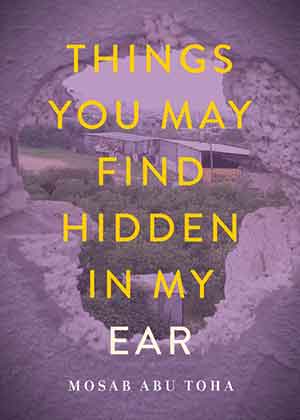

Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems from Gaza by Mosab Abu Toha

San Francisco. City Lights. 2022. 126 pages

San Francisco. City Lights. 2022. 126 pages

WHEN A PERSON chooses to read poetry, it can be for a multitude of reasons, but many of them revolve around a desire to connect with how another human being experiences and understands the world we live in. Across times and places, we want to see how others navigate through love, family life, or historic change. For most people experiencing a relatively peaceful life, making the decision to pick up poetry that has been crafted in a conflict zone is a definite attempt to find out what happens when humans are placed in some of the worst situations possible.

With the poets of the twentieth-century world wars, with which so many of us are familiar, these are often accounts of men leaving their ordinary lives to fight in conflicts away from home for a limited number of years. Poems from these periods shape our understanding of the world wars, but what happens if a person has only ever known life in a time of conflict—in fact, what happens if several generations have lived their daily life with violence ever present? This is the world that Mosab Abu Toha brings to English-speaking readers as a poet who was born in Gaza in 1992.

On the first reading of Abu Toha’s poems, the reader is struck with the accessibility of his poetry. Propelled straight into the violence and loss of the poet’s existence, there is no avoiding the horror of what it was like to grow up in a world where life is so precarious: “Images on the world of buildings / a child who was shot by an Israeli sniper / or killed during an air raid en route to school. / Her picture stares at the blackboard / while the air sits in her chair.”

On one level, Abu Toha is a poet writing for himself as he attempts to comprehend what he is living through, but Abu Toha also writes as much for his audience. Apart from the poet’s own love of the English language, the poems are composed in English so that the poet is speaking straight to a Western audience, many of whom understand little of how growing up in Gaza impacts the human residents. Abu Toha’s method of communicating this experience is therefore very comprehensible with stark imagery and language. Yet while anyone without a knowledge of the situation in Gaza could pick up the book and successfully find poems that create an emotive bridge into Gaza, this is not to say that there aren’t many layers to this poetry.

Abu Toha is very conscious of cultural heritage—a fact that is wonderfully discussed in an interview presented at the end of the book. Abu Toha speaks of his love of the British Romantic poets and also how, at school, he was steeped in the greats of Arabic poetry like ‘Antarah and Imru’ al-Qays. Abu Toha, however, does not seek to emulate the poetics and language of his predecessors but focuses on the sensibility of these poets in how they used words to create emotional responses in their readers. In many poems, Abu Toha creates short, powerful stanzas of various shapes that could work as stand-alone poems, but when read together as a whole, they create powerful statements.

In the excellent poem “Notebook,” this approach of linking very different stanzas together creates parallels with some twentieth-century Arabic poems, most notably Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani’s vital “Footnotes to the Book of the Setback.” On other levels, the two poems are very different in tone and language, and this highlights how different the situations are between that of late twentieth-century poets and those of the present day. In modern-day Gaza, Abu Toha writes of how this violence has become the norm rather than the exception for those people who knew a different life. He writes in a way that horrifies that outsider who, despite media coverage, can’t comprehend how everyday destruction and death are in Gaza. In “On a Starless Night,” he tells of the destruction of his neighbor’s house. Instead of the drama and explosion being the focus, it is the way Abu Toha notices the mundane things in the newly ruined house that help the reader realize how the horror of destruction is an everyday experience: “I never knew my neighbors still had that small TV / that the old paintings still hung on their walls / that their cat had kittens.”

Amongst all this violence, like poets he admires, Abu Toha attempts to find beauty around him, however fleeting, and he also takes the reader on philosophical explorations of his reality. The poems don’t just explore the physical experience of the conflict but also what isn’t there because of generations of conflict. Not only does he contemplate the lives lost in Gaza but also the lost experiences: not being able to grow up in family homes, not having a grave of a loved one to visit, or, for Abu Toha specifically, not being able to go on adventures in the city of Jaffa that was lost to his grandparents who fled their home to Gaza. Abu Toha explores how these voids create psychological damage that exists alongside the trauma that comes from the military violence, which is what gives this collection such power and depth.

Richard Woffenden

Leeds, UK

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!