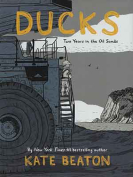

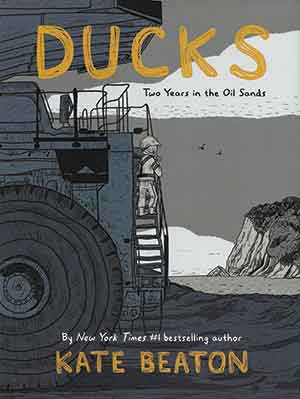

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands by Kate Beaton

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2022. 430 pages.

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2022. 430 pages.

IN THE FIRST two frames of Ducks, Kate Beaton introduces herself as the protagonist of this very personal and profoundly moving memoir: “This story starts in 2005. I am twenty-one years old.” Then, almost as an afterthought: “This is me at twenty-one. I’m much older now, and three-dimensional.” It is an arresting statement, complicated by an ingenious reference to the underlying theme of the book: the relationship between art (which in the case of a graphic artist is bidimensional) and life (whose three-dimensionality is the result of experience, knowledge, and trauma). This third dimension (painfully acquired and tamed into art) is what makes Ducks a very different—and, inevitably, a more mature and compelling—achievement than Hark! A Vagrant, the witty and hilarious webcomic that established Beaton’s reputation and popularity.

When, fresh out of college, Beaton left her native Cape Breton and took a job in the oil sands industry of northern Alberta, she could not imagine that the experience would be as affective and transformative as her keen statement, “Now I can’t extract myself from having come,” eloquently implies. Her only goal, after all, was to repay her student loans as quickly and uneventfully as possible. But in a world where men outnumber women fifty to one, female employees are alternately (or simultaneously) objects of desire and scrutiny, and variously subjected to discrimination, contempt, patronizing attitudes, sexual harassment, and assault. Inevitably, Beaton suffers the whole hypermasculinity catalog but survives the traumatic experience thanks to her candid, compassionate, inquiring attitude (“People do things here that they wouldn’t do at home”); her quirky empathy (“I like you guys. But you’re assholes”); and her growing commitment to comic art and determination to pursue it.

Her progress is marked, symbolically, by three totemic encounters. The first is with relocated buffalo (“They put them on reclaimed old mine land, a company thing”), a veiled reference to the multiple displacements caused by the oil industry—of the workers who come from all over Canada and beyond but also of the Indigenous peoples and the wildlife whose livelihoods are impacted by the mining operations. The second is with a fox who has lost a front leg but keeps prowling around the warehouse at night. Beaton’s anger (she chases the poor animal away by throwing snowballs at it) may be surprising but makes sense as a presage of her own coming injury. The third, and most significant, encounter is the news that, in April 2008, 1,600 ducks died after landing on a Syncrude tailings pond north of Fort McMurray, one of the sites at which Beaton worked. This, and a YouTube video of an elder Cree woman speaking out against the oil extraction industry, raises Beaton’s awareness of the abuse from a personal to a political level.

As we reach the end of the book, we realize that the ducks of the title represent a double tribute—to the birds who died as well as to Beaton herself (“ducky” for her older coworkers), who was able to take off and fly away from the bitumen.

Graziano Krätli

North Haven, Connecticut

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!