Afrofuturism at the Museum of Pop Culture

The Museum of Pop Culture (MoPOP) is a unique museum nestled within the Seattle Center, steps away from the Space Needle. With permanent exhibits dedicated to the infinite worlds of sci-fi, the myths and magic of fantasy, and the thrill of horror, along with an epic gallery of guitars from music legends and sections dedicated to Nirvana, Jimi Hendrix, and Pearl Jam, every collection is curated with the intention to pay homage to “the ideas and risk-taking that fuel contemporary pop culture.” And MoPOP’s latest special exhibition, Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design, is no exception.

The Museum of Pop Culture (MoPOP) is a unique museum nestled within the Seattle Center, steps away from the Space Needle. With permanent exhibits dedicated to the infinite worlds of sci-fi, the myths and magic of fantasy, and the thrill of horror, along with an epic gallery of guitars from music legends and sections dedicated to Nirvana, Jimi Hendrix, and Pearl Jam, every collection is curated with the intention to pay homage to “the ideas and risk-taking that fuel contemporary pop culture.” And MoPOP’s latest special exhibition, Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design, is no exception.

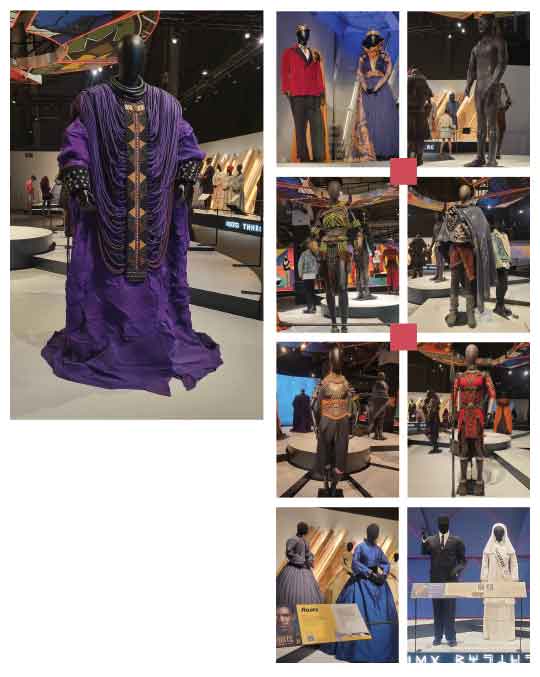

Your first taste of the exhibit begins the moment you step through the museum’s doors. The costumes that Arsenio Hall and Leslie Jones wore in the final scenes of Coming 2 America (2021) immediately catch your eye from where they regally stand on a ledge along the main staircase. As you make your way up the stairs to the third floor, where the full exhibit unfolds, Eddie Murphy and Shari Headly’s royal wear from the same movie greet you, before you’re officially introduced to Ruth E. Carter and her catalog of work.

“Afrofuturim is the African culture and diaspora using technology and intertwining it with imagination, self-expression, and an entrepreneurial spirit.” This is how Carter describes the term, and it is also how she describes her work. The sixty or so costumes on display are from blockbuster films like Selma (2014), Dolemite Is My Name (2019), Do the Right Thing (1989), Amistad (1997), Roots (2016), Malcom X (1992), and The Butler (2013). These films focus on Black history, but even though they are set in the past, the process of creating each costume included time to research “innovative or ancient design techniques that can enhance the costume.”

And enhance it does. Her work adds dimensionality, flair, and culture to the characters, giving power to incredible actors like Oprah Winfrey, Denzel Washington, Angela Bassett, Forest Whitaker, and more. Her vibrancy and attention to detail in costuming is integral to translating stories of race, politics, and culture to the big screen. As I read the plaques for each film, I was in awe of the amount of thoughtfulness and cultural commentary Carter threaded into every choice of material and color. When designing the costumes for Malcolm X, for instance, each decade was represented by a different color palette to correlate with the emotional and spiritual phases of Malcolm’s life. Even when the film deals with the harsh realities of African and Black history, the designs offer a sense of the possibility of what it means to be Black. The subtle messages she weaves in—through a pattern, a knot, the use of colors—is resistance to a world that has often attempted to keep Black people from living free and whole lives. This, too, is at the heart of Afrofuturism.

Most of the costumes line the perimeter of the room, but at the center of it all is the pinnacle of the exhibit and how most people might know of Carter’s work: the Oscar award- winning costumes from Marvel’s Black Panther (2018). When that movie came out, I was one of many Black people who filled theater seats to watch Chadwick Boseman and the rest of the cast embody the regality and beauty of tribal cultures across the African continent. The kingdom of Wakanda embodied what the continent could have been in the absence of colonialism and white supremacy. It imagined a world where Black people thrived and personified greatness. One of the best parts about the movie is that it pulled from real places, concepts, and cultures in Africa—a reminder that the Black grandeur on display in the film already exists among us.

This is especially evident in Carter’s costume design for each of the characters. The pieces on display primarily come from the coronation scene, and Carter drew her inspiration from a multitude of tribes across sub-Saharan Africa to create each look: W’Kabi’s cloak was modeled after the Lesotho wedding blanket; the Dogon tribe influenced the design for M’Baku’s grass skirt; Nakia’s ceremonial dress nods to the Suri of Ethiopia; Princess Shuri’s beaded corset comes from South Sudan’s Dinka tribe; the priestly robes of Zuri were inspired by Yoruba’s agbada; Queen Ramonda’s crown (which, along with the shoulder mantle Angela Bassett wore, was created using a 3D printer—talk about weaving technology with African culture!) paid homage to the Zulu. And, of course, the Black Panther suit itself: even though the design already existed from the comic books, Carter was still able to give it a stamp of Afrofuturism with a raised-triangle motif, because the triangle is “the sacred geometry of Africa” and ensures T’Challa is recognizable not only as a superhero but as an African king.

Perhaps my favorite part of the exhibit was that the title of every movie was written both in English and Wakandan, and the installation incorporated original work—inspired by African masks and Nigerian textiles—by Atlanta-based artist Brandon Sadler. They were small additions that didn’t distract from the main attraction but helped connect Carter’s designs so that regardless of the time period or theme, you immediately saw the overarching concept of Afrofuturism throughout.

I left feeling pride in my people and my culture and already making plans to go see the exhibit again.