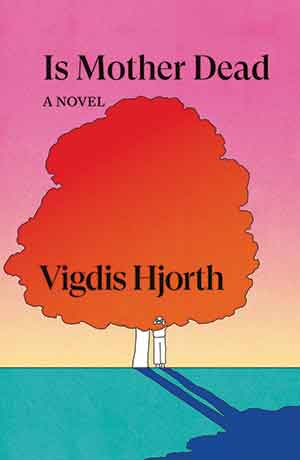

Is Mother Dead by Vigdis Hjorth

London. Verso. 2022. 330 pages.

London. Verso. 2022. 330 pages.

IT IS A MADWOMAN’S pursuit to keep chasing what you can never have, but acclaimed novelist Vigdis Hjorth understands how desperation can take hold of someone who has been thrust from the fold. In Will and Testament, Hjorth writes about a woman like herself who was the victim of sexual abuse by her father. She insists the work was fiction, but there was enough there to rile her sister to write a revenge novel clearing the family name. Hjorth claims she was trying to express what it feels like to not be seen, heard, or listened to.

In her new novel, Is Mother Dead, Hjorth revisits similar territory although biographical details have been changed and there is no mention of sexual abuse. Yet her words feel more incendiary. The voice of her first-person protagonist, Johanna, almost sixty, speaks to us in a nonstop compulsive manner, revealing herself to be a woman who has been severely scorned; her family’s bad apple. Johanna has returned to Oslo to have some sort of reckoning with her mother who at present refuses to take her calls, as does her sister Ruth, who acts as their mother’s gatekeeper. The raw and edgy narrative voice of Joanna drives this ingeniously engaging novel. At times she speaks to us with an ugly aggressiveness that seems to be her default setting. Yet at other times we listen to her soften and reflect upon her astutely sober remembrances of a childhood from which she hasn’t recovered. She wonders why she feels she must see her mother again now; it has been almost three decades since she left her. She asks herself, “Is it because I myself now stand on the threshold of the age of reflection? Because I no longer look merely ahead, but also back? Because I have a grandchild, is it a form of sentimentality, is it this never again with which I find it hard to reconcile.”

It remains unclear what caused such a complete familial rupture. It’s true Johanna didn’t attend her father’s funeral, which embarrassed her mother. And earlier on, she did divorce her first husband and impulsively marry a man she fell in love with; someone she met in a watercolor painting class. She left with him to go far away. She also abandoned a career in law that her father very much wanted for her to pursue her calling to make art, which has brought her the only solace she has ever known. Even as a kid, she recalls, “When I drew I got away from myself, or maybe I got away from Mum.” But the particular pathology of her childhood home remains mysterious to us, although clues are presented that indicate her father’s domineering nature and mother’s timidity were key factors.

Some of the most moving passages are tender recollections of her mother. There were the few times her mother showed her affection, but they were often short-circuited when her father appeared. She drew great pleasure from her mother’s joy in her first drawings, which were of bunches of roses. Her father always mocked her artistic aspirations. Johanna remembers the night she witnessed her mother using a razor blade to cut thin white lines on her forearms and how aghast she was by her mother’s desperation. Johanna felt the same exasperation herself when she stopped eating at fourteen. But there aren’t enough vivid memories for her from which to draw sustenance; always, there is an aching void. Hjorth’s Joanna is forced to recognize that “Mum has become a foreign country, she belongs to a mythical age; unlike Ruth I can’t imagine her with a body that has an expiry date.” And, she realizes, “I never had an honest conversation with her.” We wonder why she thinks she can now, particularly because her mother remains so angry and fearful of her; so outraged by her irreverence.

When she starts stalking her mother, we worry things are getting out of hand. But author Hjorth keeps her alter ego Johanna in tow—allowing her to venture only so far into a sort of dismantled madness before pulling her back again. Johanna watches her mother go on errands and stands increasingly close to her but remains hidden. She watches her mother stop at a church and cry quietly in one of the pews and hopes for the briefest of moments that the tears are for her. But she knows better. She’s been unloved for a long time.

Hjorth is an intoxicating writer who manages to somehow infuse her fictional wanderings with a strong underpinning of personal truths. We feel her presence always lurking beneath Johanna. And we understand how much still remains unsaid.

Elaine Margolin

Merrick, New York

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!