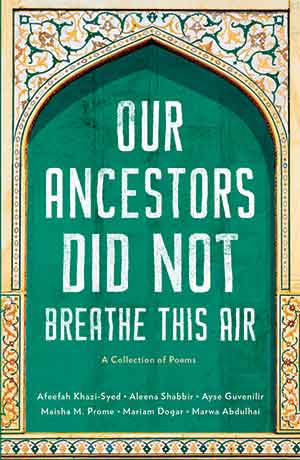

Our Ancestors Did Not Breathe This Air by Afeefah Khazi-Syed, Aleena Shabbir, Ayse Guvenilir, Maisha M. Prome, Mariam Dogar, & Marwa Abdulhai

Rockville, Maryland. Beltway Editions. 2022. 191 pages.

Rockville, Maryland. Beltway Editions. 2022. 191 pages.

“OUR JOURNEY BEGAN with a simple challenge among college friends. One week. One poem. One story to tell.” This was the task that six Muslim women, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) undergraduates at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, set for themselves. This wide-ranging collection pushes boundaries, challenging the monolithic view of Muslim women but also the stereotype that STEM is dominated by male, left-brain thinkers unlikely to be interested in poetry, much less inclined to write it. But these women, all now graduates of MIT, are both scientists as well as talented, developing poets who are always mindful of their ancestors who “did not breathe this air.” As immigrants, or daughters of immigrants, these women explore through poetry that territory between the cultures of their ancestors and the liminal space in which they find themselves.

In keeping with their promise to “piece together an ode to the places and people we come from,” Afeefah Khazi-Syed observes in “Parachute” that whenever she holds a bowl of coconut oil in her hands, she thinks of the hands of generations of her ancestors and how “each and every one of them / must have also moved like yours / working through knots of /carelessness and exhaustion.”

Aleena Shabbir asks us to reconsider the meaning of “home.” Home, she suggests, is not just a physical place but is made up of the various homes we build out of:

The hugs, warmth, laughter we collected

Through the years

All these homes use so much space

Not on the ground

But the timeshares in my head

Completely owned by mortal angels.

In addition to the surprising image of “the timeshares in my head,” there is an endearing wisdom in the poem that perhaps can only be described best by an immigrant far from home who creates her own home in the warmth of companionship.

Dismantling another STEM stereotype, these scientists also have a sense of humor. In her poem “Why I Don’t Celebrate Father’s Day,” when Maisha M. Prome presented her dad with a Father’s Day card, “He just looked at it and said, / Go give it to your mom.” On second reading, I wonder if this is intended to be humorous or instead an acknowledgment of the greater role that mothers play in childrearing.

In the section entitled “On Faith,” Ayse Guvenilir speaks to the emptiness left inside a person who is estranged from her religion about which she, in fact, may be quite ambivalent.

i need to pray after this

it’s been awhile and it makes me feel

like there’s something missing from inside my chest

like breaths I breathe are borrowed

like exhaling into Allahu’akbar

might seal these holes

What comes to this reader’s mind is the question, After what does she feel this need for prayer? Was it a specific event or the accumulation of microaggressions that leaves one exhausted and in search of a source of strength? It is made explicit in “A Letter to the Reader” that the pandemic as well as confronting “deep-rooted apartheid, systemic injustice, and longstanding conflict” has informed many of the poems in this anthology. One can imagine many other things in this turbulent world that might also move one to prayer. Other poets in this anthology find strength in collective action. But in her poem, Guvenilir leaves the specifics open to the reader to ponder; a wise move that makes the poem more enigmatic while emphasizing the need for some spiritual connection in a world gone mad.

Marwa Abdulhai’s poem “zubaan,” which appears in the section called “On Tongues,” is presented in a bilingual format with the Arabic alongside the English. In it, she notes, “Allah created us of different nations and tribes / so that we may know one another / can someone tell me / where the peace of our nation has gone?” This is the question that people across the world are asking themselves at this very moment. Putting it in poetry makes the question more urgent yet maddeningly opaque. Where did “the peace of our nation” go? And how can we get it back, if in fact we ever possessed it?

Mariam Dogar describes her feelings of abandonment and ambivalence in “it’s not us” in incandescent images.

the stars descended slowly

glittering warning signs and whispers

the moon’s ending, instead, was abrupt

our last hug so swift it felt like a punch.

At the risk of further pain, the poet again gambles on intimacy and starts . . .

to move towards you again

the walls inside me tighten

they say: no promise is but a plan

challenge to above

a gamble with ourselves.

Could this story of attraction and withdrawal, which on the surface appears to be about love, also be a metaphor, in fact, for the immigrant experience? One who reaches out toward the promise of a new life in a new land, but in moving toward that place of freedom and fulfillment, she holds back momentarily, reluctant to commit, in effect, clinging to the memory of her ancestors. Must we abandon our ancestors to embrace this new challenge? Whatever one might think, there is hopefulness in this poem; a willingness to gamble.

This optimism epitomizes much of the poetry in Our Ancestors Did Not Breath This Air. The collection forms a choir of praise for the love and strength instilled in these women by their ancestors as well as the optimism and courage with which they go forward into an uncertain world.

Jonathan Harrington

Mérida, Yucatán, México

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!