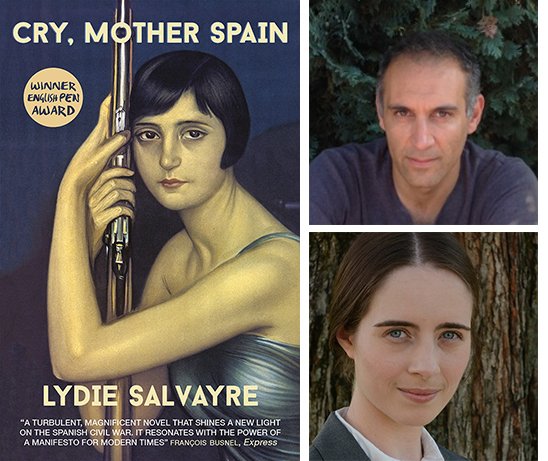

Translating Lydie Salvayre’s Cry, Mother Spain: A Conversation with Ben Faccini

Ben Faccini is a novelist, writer, and translator based in London. He was born in England and brought up in France and Italy. He worked in Paris for a joint UNESCO/UNICEF education program for disadvantaged children around the world. He is the author of several books, including The Water-Breather (Flamingo, HarperCollins, 2002) and The Incomplete Husband (Portobello Books, 2007).

I recently corresponded with Faccini to discuss his translation of Lydie Salvayre’s novel Cry, Mother Spain (MacLehose Press, 2016), which won the Prix Goncourt in 2014 as Pas pleurer. The novel is an enthralling read based on the author’s mother, Montse, and her experiences during the Spanish Civil War, from which she fled to France as a refugee. The book’s narrator intersperses her mother’s oral history with extensive paraphrases from Georges Bernanos’s eyewitness account of the conflict, Les Grands Cimetières sous la lune (1938; Eng. A Diary of My Times, 1938). Montse’s passages reflect her manner of speaking: she frequently interjects phrases in Spanish as well as words in “fragnol,” or Spanish-inflected French. The linguistic range of the novel makes it particularly interesting from a translation perspective.

Kelsey Madsen: What prompted you to translate Cry, Mother Spain (French title: Pas pleurer)?

Ben Faccini: I read Pas Pleurer for a British publisher, MacLehose Press, before it won the Prix Goncourt. There was already considerable interest within the publishing house for the book’s story and its innovative narratorial style. I read it in one sitting and really felt it was something different, something gutsy and lyrical at the same time. I agreed there and then to translate it. I fell for the language, for the voice, for the mixing of languages, for the setting, for the confidence of the opinions, its anarchy in general—and for the striking parallels with our times.

I fell for the language, for the voice, for the mixing of languages, for the setting, for the confidence of the opinions, its anarchy in general—and for the striking parallels with our times.

Madsen: Could you explain the choice behind the translation’s title, Cry, Mother Spain? I found the choice somewhat surprising since it removes the negative present in the French (a more literal translation would be “Don’t Cry”). The English title is reminiscent of Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country (1948)—is that allusion intended?

Faccini: As you say, it’s not an obvious translation at all. I played around with variations of “Don’t Cry” and other options and found each one to be too saccharine, too reminiscent of other works. I spoke to Lydie Salvayre about my concerns, and we talked through the reasons she gave the book its title of Pas pleurer. She told me that it was very much Montse’s inner voice, refusing to cry although her circumstances were dreadful—as if, in fact, someone were taunting her, goading Montse to tears. This is how I thought of Cry, Mother Spain as if that were the hounding voice in Montse’s head as she fled her country—and perhaps at the back of my mind there was a clin d’oeil, some subconscious reference to Alan Paton’s book. I felt it important, too, to add in the idea of the “mother” in all senses of the word as this book is very much about motherhood, memory, about looking back, addressing an elderly (fading) parent and country.

Madsen: Pas pleurer poses some linguistic challenges given Salvayre’s use of fragnol and Spanish. How did you choose to approach these passages?

Faccini: I knew that the fragnol had to be preserved in some way. What is understandable in Spanish to francophone readers is not necessarily comprehensible to anglophone readers. Thousands of French speakers will have read the book and enjoyed it without speaking Spanish. I couldn’t take that risk in English; not translating long passages of Spanish was not an option. I decided to try and concentrate on words in the French and the Spanish that had a Latin echo in the English, thereby uniting the three languages, and playing around with some of the fragnol. The translation, obviously, added the third language of English into the mix, but anglophone readers had to be aware that Montse spoke in a mixture of French and Spanish, yet also that Spanish was the language of the context and the language underpinning the fragnol. I hope I managed this almost impossible balancing act.

I decided to try and concentrate on words in the French and the Spanish that had a Latin echo in the English, thereby uniting the three languages, and playing around with some of the fragnol.

Madsen: Could you comment on your impression of the timeliness of this particular novel, given the current political climate? Salvayre hints at this in the novel itself, without going into detail.

Faccini: The novel doesn’t shy away from drawing parallels with current times, and I think that is one of its great strengths. It does this, however, in a subtle manner—nothing is spelled out too clearly. The reader is asked to come to his or her own conclusions. What is striking is how quickly society breaks down at a micro level, in the village, within the family, how division and hatred are sown. We see this in close detail, how civil war takes hold. The scenes in the village are quite brilliant in their depiction of human fickleness, ignorance, and aggression. Bernanos chronicles the national descent into war, but we are given unique insight into the unfolding of the war at the village level. The book does feel like a wake-up call to the world. This could happen anywhere.

Madsen: Cry, Mother Spain was published in 2016 in the UK, followed by a paperback edition this summer. Do you know if there are plans to release the book in the United States?

Faccini: I think there are plans to approach small US publishers—and certainly if there are any US publishers out there who would be interested in discussing a US edition of the book, I’m sure MacLehose Press would be delighted to hear from them. It would be fantastic if the book gained a wider readership in the US.

Madsen: Have you read any recently published French works? Any recommendations?

Faccini: I very much enjoyed Violaine Huisman’s Fugitive parce que reine (2018; The volatile queen), which is going to be published by Gallimard. It’s got the most amazing style and packs a real punch in terms of narrative. I also enjoyed Jean-Luc Seigle’s highly poetic Femme à mobylette (2017; Woman on a moped), which digs deep into rural poverty in France. Kaouther Adimi’s Nos Richesses (2017; Our riches) is particularly good on the legacy of the Algerian war of independence and the whole colonial period. Brigitte Giraud’s Un Loup pour l’homme (2017; A wolf for a man) also cleverly delves into this period. Although it came out earlier this year, I loved Mahi Binebine’s Le Fou du roi (2017; The king’s buffoon) set in the royal court in Morocco, but with a deeply personal and shocking twist. [Editorial note: Nisrine Slitine El Mghari’s review of Le Fou du roi is forthcoming in the January issue of WLT.]

Madsen: Who are some of your favorite French-language authors?

Faccini: Flaubert (always Flaubert). Maupassant. Vercors, Le Silence de la mer (1942; Eng. The Silence of the Sea, 2002). Marguerite Duras. I have a particular love too for African writers: Léonora Miano, Alain Mabanckou, Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s Tram 83 (2014; Eng. 2015).

Madsen: Do you have any current literary projects?

Faccini: I’m trying to find time to do a bit of my own fiction writing at the moment. When I write I find it helpful to concentrate on reading foreign-language (French and Italian) books so my writing (in English) remains as free of unconscious influences as possible.

October 2017