Introducing the Poeminimum: A Brief Celebration of Efraín Huerta’s Centennial

in memoriam Kenny Kahn

A trio of important Mexican writers was born in 1914: Octavio Paz, José Revueltas, and Efraín Huerta. In the English-language world, Paz has obviously come out the winner, in terms of sheer readership and international visibility—for him the complicated process of world literature canonization can be at least partially attributed to the fortunate combination of superbly talented translator Eliot Weinberger, his first English-language publishers at New Directions, and, eventually, the Nobel Prize, which he won in 1990 after winning the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 1982. Paz was a formidable presence, an institution in the Mexican literary world, and his shadow still looms large. Revueltas, a novelist, essayist, and short-story writer whose revolutionary political activity began landing him in jail from the age of fourteen, remains mostly untranslated, though Paz called him “one of the best writers of my generation and one of Mexico’s purest men.”

I got my own start translating, as a young teenager, by fiddling with excerpts from a copy of Paz’s Collected Poems I purchased at a Sanborn’s in Mexico State, inspired by growing up somewhere between English and Spanish, but today I am most interested in the work of Efraín Huerta, who died in 1982, for his continual defiance of stagnation and insistence on evolving within both the contemporary political and lyrical contexts, and for his simultaneous embrace of a sinister humor and a deeply tragic solemnity.

Huerta’s definitive masterwork is his third book, Los hombres del alba (Men of dawn), written about “those with crazed dogs / where their hearts belong,” published after the ten years it took to compose in 1944. CONACULTA has published a highly recommended facsimile edition to celebrate this year’s centennial—and have even produced an accompanying book trailer.

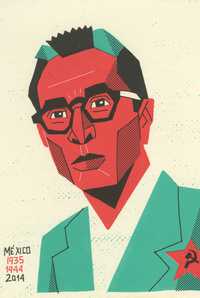

Alderete, from the book El Gran

Cocodrilo en treinta poemínimos,

published by the Fondo de

Cultura Económica.

In addition to his career as a poet, Huerta was an important film critic—his work remains influential in Mexico and throughout Latin America—and a political activist significantly to the left of Paz. (Like Revueltas, Huerta was kicked out of the Mexican Communist Party in the early 1940s for his restless questioning of the status quo.) In the 1950s, Huerta founded the avant-garde school of Crocodilism—a name that competes with the Colombian Nothing-ists for top slot on my personal list of favorite avant-garde endonyms from Latin America—which earned him his enduring nickname, El Gran Cocodrilo.

One of Huerta’s final books collects his attempts at developing a new short form, which he coined the poemínimo (poeminimum). These poems belong to the Latin American tradition of reinventing the short poem, typically more important for their underlying theory than for their quality or innovation, including fellow Mexican poet Juan José Tablada’s Un día (1919), the first collection of haiku published in the Americas, and the cosmopolitan Ecuadoran poet Jorge Carrera Andrade’s Microgramas (1940). Huerta’s poeminimums combine elements of the aphorism, epigraph, and haiku. The best are characterized by their subversive humor and the shameless punning that makes many of them almost impossible to translate. Mostly well received, poet-critic José Emilio Pacheco wrote that Huerta made the poeminimum as much his own as Neruda had the ode, while Paz, in a characteristic backhanded compliment, referred to them as chistes (jests).

I only discovered Huerta’s poemínimos some forty-five days ago, when I stumbled across a tattered first edition of Estampida de poemínimos (1980) in the Baja Californian poet Roberto Castillo’s library in Playas de Tijuana. Fortunately, Castillo had just purchased the centennial edition of Huerta’s Collected Works, and when he sent me home with the book I began to translate it with the permission of David Huerta, Efrain’s son, an important poet and kindhearted man.

In celebration of Efraín Huerta’s centennial, and in hopes that his work will receive the greater recognition it deserves outside of Mexico, I’m honored to present the first five poemínimos to be translated into English, which I’ve chosen both because they are representative of the form and because each pertains to the life and work of the poet.

Ay Poet

First

Of all:

It pleases me

Enormously

To be

A good

Secondhand

Poet

From the

Third

World

Commandment Ex

Thou shalt

Not covet

Thy

Neighbor’s

Poetry

No Remedy

& to

Us

The

Blessed

Poets

Will belong

The

Kingdom

Of

Breasts

Cruelty

From the

Fallen

Poet-tree

Everyone

Chops

Firewood

Slogan

Freedom

For

The

Poetical

Prisoners!