Everything Everywhere All at Once: Cinema Is a Toolbox, and So What?

A film scholar breaks down this “head-spinner” of a film in which Evelyn Wang can link to the minds of her selves in other realities, thereby unlocking and channeling the currency of newfound powers and skills to defeat the bizarre threat, save her daughter, and fight the complexities of the multiverse. While doing so, the film motivates audiences to be users whose active participation in tooling and retooling for different ends makes sense of the film.

True to its title, Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), by the directing duo known as the Daniels—Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert—is an ambitious mixture of everything and everywhere. It is a head-spinner, a melting pot of spatial-temporal existence. A weird mashup of wild ideas, film styles, body-driven farce, and scatological tropes, with countless silly, obscene, or nonsensical details. For those who appreciate the idea of Asian American cinema, EEAAO might evoke a long list of recent titles. Examples include Advantageous (2015), Gook (2017), Columbus (2017), Crazy Rich Asians (2018), Searching (2018), Minding the Gap (2018), The Farewell (2019), Lucky Grandma (2019), Tigertail (2020), Minari (2020), The Half of It (2020), After Yang (2021), Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings (2021), and Turning Red (2022). Many have discussed orientalist clichés and recurring themes in such films and their predecessors, including the East–West divide, (the trap of) model minority stereotypes, generational trauma, the cultural battle between personal autonomy and family/communal values deeply rooted in the patriarchal structure, and so forth. However, more intriguing is EEAAO’s development of an audiovisual corpus that moves beyond the banality and infertility of an overused system of Chinese American visual icons (dragon, chopsticks, qipao costumes, red lanterns, etc.).

To that end, the film falls into the form of what I call a “cinema of toolboxes.” It is designed to be practical. Like a manual, it artfully provides tested and untested tools, techniques, and a superabundance of registers to help people access and absorb what is best described—as the Daniels put it at the film’s end—using the Chinese idiom tianma xingkong: literally, “the heavenly horse crosses the sky,” which means being imaginative, bold, and unconstrained.

In and Out of the Circle

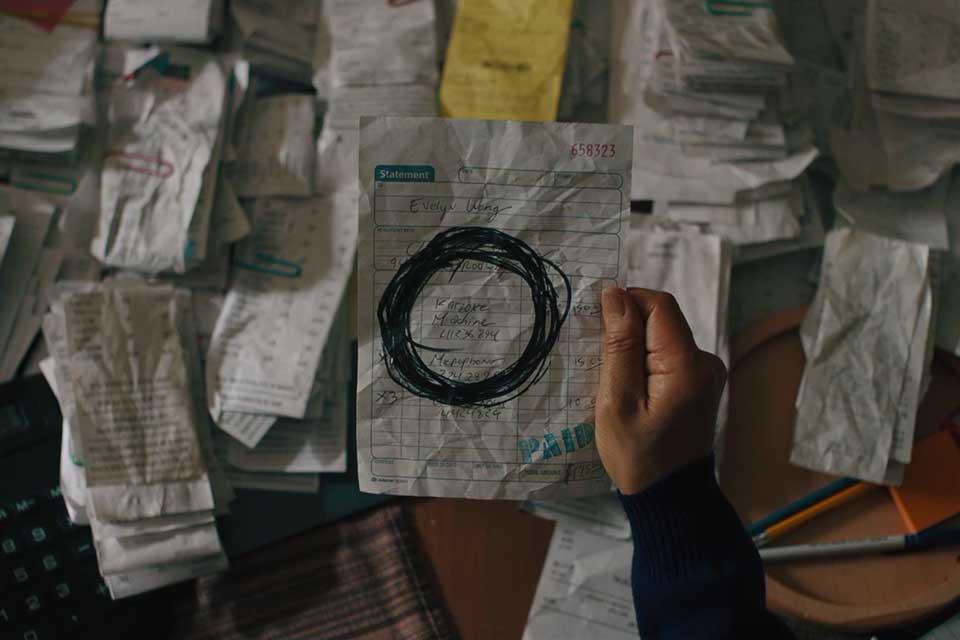

An exhausted, middle-aged Chinese American woman who is a laundromat owner, Evelyn Wang (Michelle Yeoh), is swamped with a number of ongoing problems all at once: tax audit, unhappy marriage, her daughter’s queer sexuality, a conservative and demanding father who is visiting and knows little English, and stressful Lunar Chinese New Year party preparations. Evelyn discovers that her decisions in the past bring parallel universes into existence; as the chosen one to prevent the most powerful evil being from annihilating life throughout the multiverse, she must fight back by traveling across the universes to connect her other selves. The most compelling visual sign of Evelyn’s chaotic life is the circle, around and for which EEAAO structures itself as a narrative of fixing and filling up. The onset of the story is a circular mirror reflecting three characters: Evelyn, Waymond (Ke Huy Quan), and their daughter, Joy (Stephanie Hsu). It is an illusion of family happiness through the looking glass, darkly. Then, more circles show up and establish diegetic (inside the film world) connections. Evelyn’s prime universe inside a dark hole, as big as the spinning circle of a washing machine in her laundromat, in an extreme closeup shot, embodies what seems to devour this unlikely heroine’s professional and family lives at once. Dark circles drawn by IRS auditor Deirdre (Jamie Lee Curtis) on Evelyn’s tax paperwork point to the unpluggable drain hole of the immigrant family’s business. Another circular mirror appears to be a displaced one, projecting Evelyn’s anxious face and split body/soul oscillating between her prime universe and other parallel universes. The circle has no end and yet offers a liminal space.

The circle functions as a perfect tool for the Daniels’ mise-en-scène to set up puzzles and visualize contradictions. A variety of almost-round objects flash across the screen at times. Some are embedded in the assemblage of materials that Joy/Jobu Tupaki grabs from her life and puts in the everything bagel as the ultimate embodiment of her nihilism. Some are part of Evelyn’s multiverse life setting. Most obvious is the profound circle symbol and its double: the seemingly opposing images of the Joy-made everything bagel and the googly eyes. People might read this pair as mutually complementary circles—one white circle with a black interior and the other black with a white interior—evoking the Chinese yin-yang duality that typically symbolizes the endless life cycle in a universe filled with balance and harmony. Nevertheless, the yin-yang myth, if unpacked through the hollowed-out appearance, says more about endless emptiness and the vulnerability and anxiety of being incomplete.

The bagel, where everything resides and how everywhere merges, recalls the donut metaphor from Peter Feng’s discussion of the 1982 Asian American film classic Chan Is Missing. As a mockumentary with the look of the detective film genre, Chan Is Missing interrogates the identity of a missing person, Chan Hung. For Feng, each character holds a donut that contains the possibilities of Chinese American identity within its center; each character takes one bite from the donut to access the center.[i] The big donut is “made up of all the little doughnuts—a doughnut akin to the construction of Chinese American identity that the spectator viewing Chan Is Missing is left with—is almost meaningless, almost wholly ‘hole.’”[ii] Whereas each character identifies Chan as a way of seeking to fix their own identity (Chan is who they are not), viewers must negotiate all the perspectives without being allowed to possess any of them. Each character’s bite out of the donut indicates their attempt to limit the range of Chan’s identities, which opens the interval in the donut perceived by the viewers. The space for viewers’ positions and, by extension, Asian American subjectivity, is thus expanded. This reading echoes the psychological conceptualization of the Lacanian lack in which the donut’s hole is the continuation of the space that surrounds it; only due to the hole does the donut become a donut.

In EEAAO, the everything bagel shares not only the roundness with a hole in the center, or the symbolic lack, but also the void that is both meaningless and highly functional. The hole is precisely what is not in it; likewise, the exclusion is what shapes our sense of the universe, reality, and our existence. The bagel is made of everything and filled with nothing. The circle is an enclosure that stages in depth and entraps everyone on and off the screen, as well as an open box that, cinematically, supplies a tool kit for understanding the film and seeking different positionalities.

If Chan Is Missing explores how people might discover the ways they can become Asian Americans by showing why it is impossible to know who they are as Chinese Americans, EEAAO evades the arduous clarification of the identity problem through instrumentalizing the circle as something conceptually universal (while somewhat visually Chinese/East Asian related) and by initiating a pragmatic exploration of how to fix one’s life through retooling. When traveling in and out of the circle, we circle back to the same dilemma: there is no once-and-for-all solution to ceaseless problems.

The Multiverse as a Skills Bank

In EEAAO, the multiverse seems akin to a bank of experiences, energies, and skill sets. Through verse-jumping, Evelyn can link to the minds of her selves in other realities, thereby unlocking and channeling the currency of newfound powers and skills to defeat the bizarre threat, save her daughter, and fight the complexities of the multiverse. Apart from similar examples within the long-established trope of lending/accessing others’ skills, people might also recall the series Sense8 (2015–18) in terms of one’s spatiotemporal existence as a fantastic virtual toolbox. Under the rubric of “sharing” in Sense8, human beings called “sensates” are telepathically and synchronically connected to each other if they are within the same cluster. They can share and exchange their respective feelings, knowledge, languages, and skills as a group or focus those onto one member of the cluster. While there is no multiverse, Sense8 allows for real-time “visiting” across different parts of the diegetic world. In contrast, it is not merely the realization of the multiverse but also how it works through the commonplace that shapes the major difference in EEAAO. The multiverse is a living archive of resources within which each version of Evelyn’s lifetime is usable, and the plural forms of her other and alternative experiences equip the “worst version” of herself with life-changing skill sets.

The multiverse-as-toolbox enables Evelyn to borrow skills and memories of her other selves and to access divergent possibilities of selfhood. More importantly, Evelyn’s approach to the multiverse may be seen as both self-help and outsourcing without logical or emotional incompatibility. The toolbox scenario complicates the assumed self/other binary and the mind/body dichotomy, challenging the conflicting nature of alternative world-building in the “what-if cinema” tradition that opens space for more than one narrative variable (or what scholars call “narrative cubism,” “forking paths,” and the Rashomon effect).[iii] Unlike previous cases that play with nonlinear temporalities and metafictional devices, the Daniels’ creation ends up in a utopian version of the multiverse as a mode of thinking and as a source of inexhaustible utility for whoever is trapped in the mundane.

The Daniels’ creation ends up in a utopian version of the multiverse as a mode of thinking and as a source of inexhaustible utility for whoever is trapped in the mundane.

Hands-on Aesthetics

The onscreen hand has been framed for an array of effects dating back to the birth of cinema. Both in line with and different from Wong Kar-wai’s treatment of human hands in stillness or slow motion as unspeakable attachment, or Robert Bresson’s approach to moving hands bound up with objects, labor, acts of exchange, or gestures of destruction, the hand in EEAAO is more than a synecdoche for labor and humanity in general and deserves more unpacking. Ranging from familial interaction by hand to variation in Evelyn’s hand shape or gesture as a material index to the compatible presence of the multiverse, to the ridiculous hot-dog fingers in the queer universe and the pinky-finger fight in the martial arts universe, the hand stands out as a character in and of itself. The hand dramatizes itself as in a process of producing what I call “handcrafted intimacy” once it appears onscreen.

The hand in EEAAO is more than a synecdoche for labor and humanity in general and deserves more unpacking.

For example, female/family bonding is built on the subtle working of a hand-to-hand motif literally staged in the confrontation scene. The key moment occurs right after Evelyn’s handcuffs unlock automatically when she randomly jumps into the hot-dog-finger universe for the first time and switches back. Joy/Jobu Tupaki opens Evelyn’s middle finger and ring finger by inserting her own hands (the right one still in a white glove) into the space, between which the everything bagel is made visible. From Evelyn’s perspective, we see the bagel through the space between their fingers and, disorientingly, also between the overlapping palms of their hands. The film’s dark secret exposes itself through the exchange of the two female characters’ point-of-view shots framed by hands and fingers. Central to the scene is a sense of symbiotic intimacy that emerges from mutual collision in the most straightforwardly embodied and tactile way. The boundary between mother and daughter, good and evil, powerful and powerless, manipulation and freedom, is blurred.

The intimate “handmade” style also shapes the film’s high concept. The Daniels edited the film-adjacent book A Vast, Pointless Gyration of Radioactive Rocks and Gas in Which You Happen to Occur as a wild journey through the five prevailing multiverse theories of a broad group of scientists, writers, and artists. Although they did so to compile a large set of ideas about the multiverse, nihilism, existentialism, and empathy fatigue in the film into a technical guide for their crew and cast, they chose not to overwhelm EEAAO viewers with intellectual intensity and an excess of dazzling high-tech spectacles. In contrast with the investment and cost of typical Hollywood sci-fi blockbusters, only a five-person team created the almost five hundred visual-effects shots in EEAAO. In addition to the clever use of the hot-dog-finger gloves as puppets, the Daniels’ “practical effects” also include the creation of verse jumping through cheap LED light panels and handheld stock footage that Daniel Kwan had filmed on the streets of New York, as Michelle Yeoh on the set pretended to fly through and across the space of the multiverse.

What does the multiverse look like? The key turns out to be the Daniels’ low-budget strategy of simplifying the multiverse theory through use of Evelyn’s changing face as an all-in-one cinematic tool. The Daniels’ technical experiment resembles a playful take on the vernacular genre of social media profile pictures. What one may call “the infinite Evelyn montage” is an assemblage of flickering close-ups in which the heads of Evelyn’s multiverse variants are superimposed over one another against diverse—sometimes realistic, sometimes foppish, vulgar, and poorly resolved—backgrounds: chef, opera singer, movie star, martial arts heroine, dominatrix, drawing, piñata, and queer woman with hot-dog fingers. While fans enjoy discussing whether or how many different takes were needed to create those variants in a frame-by-frame mode, the film crew have shared their tips for using Photoshop and the green-screen backdrop to capture Evelyn’s gestures. Evelyn’s face is represented as sculpture, as animation, as a skull, as a digital meme, as a screenshot of a Zoom meeting, in security-camera footage, melting into an oil painting, imprinted on a tree, on grapes, and on someone else’s body.

The down-to-earth virtuosity of creating the multiverse through functionalities of the mundane and the vernacular is just one among many technical resources in EEAAO as a user-friendly filmmaking toolbox and hands-on guide. The skillful use of rapid match cuts and graphic juxtaposition creates a dual impression that the modes of Evelyn’s existence vary though her face is identical and her variants’ direct look at us remains the same. It is the gaze of Evelyn, the woman who confronts multiple versions of herself, that speaks to us who are everyday media users and makers alike and urges us to think by doing. Her instructional gaze unsettles the border between the onscreen multiverse (already multiple diegetic worlds), the internal diegetic space with uncountable layers of her own minds, and our extradiegetic reality.

It is the gaze of Evelyn, the woman who confronts multiple versions of herself, that speaks to us who are everyday media users and makers alike and urges us to think by doing.

Database Cinephilia

As Lev Manovich notes, the term database cinema recognizes the mode of filmmaking that accumulates materials, including images, sounds, narratives, and even the identities of characters, from the multiple databases formed during shooting, out of which the final cut is a unique one among many trajectories “through the conceptual space of all possible films which could have been constructed.”[iv] In this sense, EEAAO pushes the boundary of the database form in cinema since it also performs the database as a mode of viewing and cinephilic engagement. On one hand, it is an audiovisual database and a media literacy toolbox in itself that contains a complex of not only cinematic quotations but also vernacular images from multimedia sources (which might fit into “poor images,” to use Hito Steyerl’s term), whose lack of resolution and poor visibility or blurriness due to high-speed editing attest to their appropriation and displacement from the digital environment.[v] On the other hand, the film entails a database-structured imaginary that allows for one’s own nonlinear navigation of trajectories beyond the film, positioning cinephiles to dig, compare, analyze, and remake cinematic materials that might not otherwise find themselves in the same conversation. For instance, navigating EEAAO as a film of films and moving images of various kinds, one may understand the infinite Evelyn montage as reminiscent of the surreal nightmare scene in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958): Scottie’s head from the neck up superimposed on an octagonal, dizzying background that rushes by rapidly and suggests vertigo. Without using the film as a set of dissectible data tools, cinephiles would have no capacity to find among the image assortment one single frame with the title “Illuminati Symbols Hidden in Hollywood Films for One Frame.” EEAAO motivates audiences to be users whose active participation in tooling and retooling for different ends makes sense of the film. Based on their own takeaways from the film, users become film miners, archaeologists, editors, critics, translators, and (co-)producers of cinematic data sets, shaping the cinephiliac universe or another paratextual multiverse.

Based on their own takeaways from the film, users become film miners, archaeologists, editors, critics, translators, and (co-)producers of cinematic data sets, shaping the cinephiliac universe, or another paratextual multiverse.

EEAAO is a cinephile’s toolbox shaped by film history’s intertwined universes. After watching EEAAO, it is not hard for most audiences to draw connections to films like The Matrix (1999), Ratatouille (2007), and so forth. One can see through Michelle Yeoh’s and Ke Huy Quan’s real-life acting careers as metafiction, along with previous films featuring them. Clan of the White Lotus (1980), Stephen Chow’s films, especially Kung Fu Hustle (2004), The Grandmaster (2013), and other martial arts classics may come to mind for those lovers of kung fu and East Asian cinema. Some EEAAO scenes owe a clear debt to Wong Kar-wai’s style as exemplified in In the Mood for Love (2000). Some cinephiles also analyze how EEAAO cites other films supported by shot-by-shot close readings of evidence and, furthermore, how some of those cited films also refer to each other in other cinephiliac universes.[vi]

Insofar as many films arrive on global big and small screens loaded with all the ideological weight of male-dominant heteronormativity, cinephiles use EEAAO as an imperfect counterexample that holds activist potential for open dialogue across generations. One such case is an interpretation of the film with regard to Ang Lee’s The Wedding Banquet (1993) and Alice Wu’s Saving Face (2004). Also remarkable are feminist critiques of the long-winded ending through a comparison with other films involving the “tiger mom” character type as an agent of patriarchal authority and Chinese American multigenerational mother-daughter entanglement. EEAAO’s unsatisfying final resolution boils down to “being kind,” taught by Evelyn’s husband, and the baffling reconciliation among all the characters. The belief that love resolves all struggles is clear-cut and limited, contradicting the apparent richness of the queerness built up earlier in the film.

* * *

Overall, well versed in spectacular film elements and hypernormalized grand theories, EEAAO shows cinema as a toolbox on demand. Now that we see the functioning of toolbox cinema, let’s think further and conclude with what EEAAO is not and what it fails to do. Film history includes a long list of titles that seek to raise questions and end up with the unresolved and the unreconciled, such as the older Fritz Lang’s M (1931), Nagisa Ōshima’s Death by Hanging (1969), and Lizzie Borden’s Born in Flames (1983), or the more recent Lee Chang-dong’s Burning (2018). These films cannot be oversimplified as stories with unsettling or tragical endings. Their questioning heart is not defined by genre, auteurship, or superficially open structures but by a belief that the only possible conclusion is its own lack, a resolution as fiction and mystery that awaits further inquiries and exploration. By contrast, what counts as a toolbox film is neither a never-ending question mark nor an ellipsis. It holds on to the answers and avoids discomfort in the uncertain and the unknown. But it does not necessarily resolve any given problems, even if it claims to do so. Instead, it is simply about providing space in which audiences identify relatable issues, reinforce solution-oriented mind-sets, and ultimately must benefit from the comfort of grabbing something customized for their own purposes. People use the film as their “tax filing guide” (for first-generation immigrants who need their native-speaking child to translate), first aid kit, therapy instructions, or emergency survival kit (for anyone suffering from family crisis), gaming skills bundle (for amateur media creators), self-help handbook (for young skeptics and nihilists), intermultiverse travel guide (for sci-fi lovers, cinephiles, escape artists of the real world, etc.), and so on.

A stimulating scene that stays with many people long after they leave the theater depicts the conversation between a pair of sentient googly-eyed rocks overlooking a mountain (“the Grand Canyon that feels distinctly Asian American,” according to Daniel Kwan) with no spoken dialogue or audio but only onscreen text. As I observe, many viewers across the Asia-Pacific share both their excitement and confusion via social media: Why do two talking rocks in silent mode make our tears well up? Why couldn’t the multiverse journey have stopped here? Even sharper questions arise: When one of the rocks decides to fling itself (not necessarily herself) off the cliff, why does the other (supposedly Evelyn’s variant) follow the same path? Do we have to imagine the two rocks as mother and daughter? Are we allowed to question their dual action of falling as the theme of love that the film sticks to? Moreover, can we refuse to see love as the ultimate and only answer, especially to the mother-daughter conflict?

For me, overpackaged with a mechanical desire to be identifiable with or applicable to the everyman’s experience, the film turns to an opportunistic media-saturated style for tools that will maximize its target audience’s engagement. The style begins with freshness and novelty and then dilutes both. The promotional words in the collection of free, printable “Multiverse Mother’s Day Cards” that the film’s production company, A24, has released for fans explain a lot. We just need to turn the declarative sentences, expressions of hijacked idealized motherhood, into rhetorical questions or their negative forms.

“You [don’t have to be] best [or perfect] mom in every world.”

“You are [not] my everything. [Me neither.]”

“We [don’t have to be] cookin’ up a functional mother-daughter relationship.”

Isn’t being functional a social construct anyway?

EEAAO is an allegory of both the power and the uselessness of its own all-purpose toolbox form. Evelyn is the more vital “tool,” as a mom and a wife, for declaring that “I still love you across all the universes.” Once Evelyn’s final choice is made, she has no real agency to go beyond the confession of love with a face of self-acceptance. The onscreen presence of more Asian American heroines like Evelyn and Joy is in great need. As this phenomenal film renders unconventional female and queer protagonists visible and makes them shine, one may expect much that the filmmakers have yet to unpack. At least the local laundromat that Evelyn owns is a promising hybrid microworld. A work, home, and social space that is also gendered, multiracial, multilingual, and indicative of class deserves much more cinematic development. However, it remains a stage of paradoxes and false propositions, a well-decorated wasteland.

As this phenomenal film renders unconventional female and queer protagonists visible and makes them shine, one may expect much that the filmmakers have yet to unpack.

The best-equipped toolbox is not a master key. Everyone might enjoy a “wow” moment while watching EEAAO and then find it too difficult, only to answer “so what?” We might have to just add more question marks. Can EEAAO, with its ideology of multiverse love, not reproduce meanings of functional motherhood, wifehood, daughterhood, and womanhood that exclude nonnormative modes of being, thinking, and doing? Is there a real way out? The film’s most realistic response to its own restriction is perhaps concealed in its alternative title, as translated in Taiwan, Made duochong yuzhou (literally “The Multiverses of Mother”). This equivocal term, which is a Chinese pun, also means “fucking the multiverse.”

University of Oklahoma

[i] There is another interesting bit of food rhetoric in Chan Is Missing. The apple pie baked by a Chinatown bakery is an example that combines the American form with Chinese ingredients/techniques. The character George’s original line in the film is: “It is a definite American form, you know, pie, okay. And it looks just like any other apple pie, but it doesn’t taste like any other apple pie, you eat it. And that’s because many Chinese baking techniques has gone into it, and when we deal with our everyday lives, that’s what we have to do.” Arguably, the embodiment of Chinese American negotiation and its connection to the Asian-American identity crisis might be comparable to the symbolic potential of the bagel in the Daniels’ work.

[ii] Peter X Feng, Screening Asian Americans (Rutgers University Press, 2002), 168.

[iii] See David Bordwell, “Film Futures,” SubStance 31, no. 1 (2002): 88–104; David S. Diffrient, “Alternate Futures, Contradictory Pasts: Forking Paths and Cubist Narratives in Contemporary Film,” Screening the Past 20 (Dec. 2006). Those films often share a multiperspectival or episodic approach to storytelling that either presents mutually exclusive lines of action in a gamelike mode, leading to contradictory pasts or alternate futures, or disperses points of view across a spectrum of individuals whose contrasting, unreliable testimonies portend their ultimate physical or emotional incompatibility. Well-known examples include Blind Chance (1987), Run Lola Run (1998), and Hero (2002).

[iv] Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (MIT Press, 2001), 237. Every filmmaker may encounter the database problem in every film, but only a few have done this self-consciously. Manovich notes Dziga Vertov and Peter Greenaway as two examples. For more discussions, see Lev Manovich, “Database as Symbolic Form,” Convergence 5, no. 2 (June 1999): 80–99; Lev Manovich, Soft Cinema: Navigating the Database (MIT Press, 2005).

[v] See Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image,” e-flux 10 (November 2009).

[vi] Based on tiny details or the overall narrative setting, people have pointed out more cinephiliac references, including 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) for the prehistoric scene of the hot-dog-fingers universe, A Clockwork Orange (1971) for Jobu Tupaki’s makeup, The Shining (1980) for the door breaking, the Kingsman film series for Joy/Jobu Tupaki’s fight with the police, Paprika (2006) for the fake end-credits scene as Daniel Kwan’s self-reflexive reference, The Exorcist (1973) for swiveling one’s head 360 degrees, the Rick and Morty TV series (2013–) for the set-up of wearing glasses to see the multiverse, Ready Player One (2018) for the remote control of one’s body through VR glasses, Joker (2019) for Evelyn’s job of holding a signboard in one of the universes, among many others.