The Year of Colorful Reading

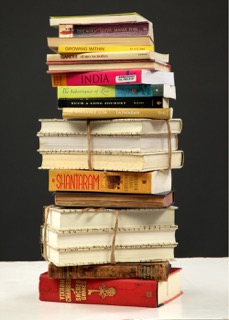

Indian books. Photo © Doug Wolf.

I’m reading nonwhite this year. That’s what many readers/writers around the world are proclaiming. What they mean is that they’re focusing 2015 on reading authors from around the world. What they’re gleaning is more worldliness and exposure to entirely different literary styles that may just inform their writing and therefore the publishing scene in years to come.

Reading nonwhite is my personal extension of another recent trend, the Year of Reading Women. In that endeavor, female readers/writers took it upon themselves to eschew reading male authors in favor of their sisters following results of the VIDA counts, which document the lack of gender equality in contemporary literary culture by counting the bylines and publishing credits from periodicals and literary journals. Women aren’t being published or awarded or granted editing and publishing positions to the same extent as the other sex.

This trend of women supporting other women can be seen in such efforts as Reese Witherspoon’s decision to start a pro-woman film production company and Lily Tomlin’s and Jane Fonda’s endorsement of a new Netflix show that features disproportionately female names in the credits.

The Journey Begins

When my own Year of Colorful Reading began, I knew of the VIDA angle but was unaware of the nonwhite one. Mine began by discovering a dearth of books by Indian writers. I was sitting in my living room back in December, looking at a stack of books by authors with Indian names. It must have reached three feet tall and grew after each trip to the library. Most of these titles, though, were by diaspora writers. I wanted more. And I knew from living in India and other countries that they existed.

They do. This magazine and other resources such as Three Percent guided me in the right direction to find them. Three Percent is a website and podcast, produced by the University of Rochester, that brings translated international works to American readers. It took its name from the oft-quoted statistic that of all the books US publishers annually churn out, only three in every hundred are international translations. Dig a little deeper and you’ll see that classics and reprints comprise most of that percentage.

Is That All There Is?

The void I found in that stack of Indian books was somewhere in that less-than three percent. My compelling desire to find them was the proverbial last straw. Something else was spurring me to embark on this colorful journey: missing the rigorous daily engagement with other cultures that life abroad affords. Having repatriated two years ago, I no longer have the luxury of hitting up the book wallah at the Santa Cruz train station in Mumbai. When I walk into any local and chain bookstores and ask clerks for suggestions for authors from beyond US borders, their responses are, almost without exception, Jhumpa Lahiri and Salman Rushdie. No one even mentions Anita or Kiran Desai.

Something else was spurring me to embark on this colorful journey: missing the rigorous daily engagement with other cultures that life abroad affords.

By the time I started asking librarians, more questions popped up. What about titles from Sri Lanka or Pakistan, Bangladesh or Kashmir? What famous authors come out of Tibet and Nepal and . . . ? Spinning out geographically evinced the journey before me: Why not read the world? Devote a whole year to it? A Year of Colorful Reading. And so I moved beyond the walls of bookstores and libraries and entered the cybersphere.

Enter Sunili Govinnage, an Australian human rights lawyer and freelance writer. Govinnage would end up reading twenty-five non-Western sci-fi, fantasy, young-adult, and chick lit books on her literary gap year, but before doing so she wrote in The Guardian, “I know accusations of reverse racism are pending.” And, considering the racial tension prevalent in today’s news, they did. Arguments and attacks about race and racism littered the comments section of her online article.

“No doubt people will say I am limiting myself by purposely avoiding books on the basis of an arbitrary factor,” Govinnage wrote. “But it’s the opposite: I see it as a way of opening myself up to new stories, rather than re-iterations of the same formulaic fables we’ve heard time and time again.”

That gets at a major problem in publishing today: the chicken-and-egg effect. Publishers say readers don’t ask for international titles. Yet readers don’t know to ask for international titles because we’re not given exposure to them. Which makes me wonder: When people read big-name foreign authors, do they think they really know anything about those cultures? Are those authors giving Western readers anything beyond a perpetuation of media propaganda?

That question originated last year when I was reading another diasporic Indian book, Bharati Mukherjee’s Miss New India. In it, one of her peripheral characters was an Indian-American novelist. That novelist’s claimed to fame? Writing Indian books for American women. Such was the problem with entirely too many books in my stack. And it’s also indicative of mainstream publishers going with the flow of the status quo instead of trusting readers’ curiosity about the world of literature outside Western borders. Readers may enjoy books from the diaspora, but give us a chance to see the world without Western goggles. We’re curious. We’re also hungry for globalization to translate to our reading lives. Let us make the decision to learn about other cultures through their literature, and then perhaps decide to travel there or, in my case, to live there.

Can You Relate?

Memories of my life in India sprang to life upon reading Basharat Peer’s memoir, Curfewed Night. One of very few diasporic authors in this year’s list, he related experiences I couldn’t have expected when setting forth on my colorful expedition. We shared similar quandaries in two of India’s most prominent cities. The Muslim Kashmiri writer witnessed racism and other hardships when searching for a rental apartment in early 2000s Delhi. My experience happened in Mumbai.

Procuring my own cell phone and SIM card proved damned near impossible after my phone and passport were stolen in 2010. It took weeks. Only my Indian friends could set me up with a Vodaphone package, but no one ever explained why. The reason, it seems, was a 2008 terrorist siege, India’s own version of September 11, at the hands of David Headley. Headley could pass as white and carried dual passports, one of them American. Over the course of weeks he staked out places to bomb in Mumbai, conducting business with a phone using a SIM card purchased locally. He and other terrorists were responsible for bombing hotels, a train station, a Jewish center, and other places. The siege lasted three days and killed more than 160 people. India thought it could prevent such attacks from happening again by writing the Prevention of Terrorism Act. One byproduct of that act, however, was widespread fear. Indians now feared anyone who wasn’t a nationalist.

After the theft of my phone, still ignorant of the act, I worked for a friend in an orthodox Muslim neighborhood. The residents were a step away from pitchforks and torches out of fear of my presence in their neighborhood. It was then that my friend explained the link to Headley. Peer’s rental problems, I learned from his book, also stemmed from Headley and the act, and situations like ours spread across the country like a mushroom cloud.

We often find commiseration like that in songs. Not so often in literature. That shared experience marked a brilliant awakening in me. It conjoined the writer, the reader, the world traveler, and the US resident resplendently. But mine was a rare occurrence.

It was an inability to relate that raised the ire of K. T. Bradford, a journalist covering the tech industry. Something seemed to be missing from the literary journals and online magazines she typically read. It finally induced her to make more active reading choices.

“Every time I tried to get through a magazine, I would come across stories that I didn't enjoy or that I actively hated or that offended me so much I rage-quit the issue. Go through enough of that, and you start to resist the idea of reading at all,” she wrote on xoJane. So she pointed her literary car in a different direction, choosing streets populated by women, people of color, and the LGBT community. In effect, bypassing white men.

“Cutting that one demographic out of my reading list greatly improved my enjoyment of reading short stories. That’s not to say I didn’t come across bad stories or offensive stuff in stories or other things that turned me off. I did. But I came across this stuff far less than I did previously.”

I don’t know how long Bradford felt disassociated from what she was reading to make this change. Her words, though, make me wonder why it took me so long. Perhaps it took the confluence of that need to remain connected with the world outside the US, the knee-jerk reaction to start in India (my go-to country for all things cultural), and my then-nascent feeling of disassociation with Western literature. An elective graduate school course in postcolonial British lit introduced me a decade ago to Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North and literature from many colonized parts of the world. Later, traveling to and living in various countries helped me discover Italian writer Oriana Fallaci, Indian novelist Chetan Bhagat, and indigenous Peruvian writer José María Arguedas. These were the stepping stones that ended in a commitment to the discovery of world literature, which granted me a resurgence in the joy of reading and a transformation in my own writing.

Those of us who’ve chosen this route come to the decision from varying perspectives. But publishing issues raised earlier in this essay mean we’re not clear on where to begin. We spend hours searching for direction, our literary compasses spindrift. After all, signposts like World Literature Today aren’t as ubiquitous as Us Weekly, even for the well read.

Where Are They?

We have to be looking in that direction to find it. There is no huge repository, no matter how big Google’s online library is, to find colorful books. However, to the rescue comes British writer Ann Morgan. She was among those who followed up her year of reading women by reading non-Western work. Her blog, A Year of Reading the World, contains discussions/reviews of each of the 195 + 1 books she read a few years ago. But even that task meant using Western parameters to determine which countries to read, a decision she writes about in the book that follows her blog, The World between Two Covers (published last month by Liveright). She read from the countries recognized by the United Nations, plus one she let her blog’s readers vote on (they chose Taiwan).

Consider her list of books read and suggested a priceless source when starting an international literary venture. It’s also a phenomenal resource for discovering—to coin a phrase—literary activist organizations. Some of those she considers include Literature Across Frontiers, Paper Republic, and the Writers Association of Bhutan.

Literature Across Frontiers is a European platform for literary exchange, translation, and policy debate. LAF also fosters the development of and shines a spotlight on lesser-translated works and debates policy on literature and translation. Like VIDA, the Wales-based organization does counts. Earlier this year it released research results that confirmed the UK’s three percent theory, which mirrors that of the US.

Then there’s the Paper Republic, for readers who want to know China beyond Amy Tan’s novels. One component is a literary journal of contemporary translated Chinese fiction and poetry. Another facet is a compendium of information about universities offering top-notch translation programs and various grants and awards for translators. It also keeps up with who’s translating to/from Chinese and who’s publishing these translations.

The Writers Association of Bhutan is a platform where aspiring Bhutanese writers can share their work. The group claims to be seeking financial and other assistance to publish more Bhutanese work.

The World between Two Covers is not simply a list of resources. It tells the story of Morgan’s strident efforts to reach out beyond her own national borders and far past the literary world fostered by traditional educational institutes, bookstores, and the media. Hers was a monumental journey that delights readers with stories of deep, meaningful links formed between writers, editors, translators, publishers, and fervent readers encountered along the global path. More than that, it’s a reminder of the connections between all of us who like reading, no matter which side of the pen we’re on.

We step through the age of printing and run smack dab into a fireside circle, where we listen to elders pass down oral traditions and legends.

Well written and highly engaging, this is not a poorly transcribed blog-to-book. Among the subjects Morgan tackles are the impressively progressive self-publishing industries of India and Samoa; the sensitivity of handling reviews of translated books; which genres translate into profits in other countries; the invaluableness of social media for readers around the globe as they help one another find new classic and contemporary novels, poetry, short-story collections, memoirs, and folktale anthologies; and also, one of my personal favorites, colonialism’s role in thwarting the passage of literature between cultures. Finally, an implicit line of the evolution of storytelling runs through her book and blog.

Storytelling

Witnessing that evolution is one of the funnest parts on this Colorful Reading voyage. We step into a place before readers could only handle stories told in 140 characters on Twitter. We curve around the novel’s invention. We step through the age of printing and run smack dab into a fireside circle, where we listen to elders pass down oral traditions and legends. It’s liberating, actually, reading work that’s not crammed into the confines and canons of Western literature, work that emphasizes dynamics, even poignancy and escapism, differently. We are the beneficiaries of these different literary styles—we the readers, writers, translators, editors, and publishers.

My devotion to world literature won’t stop like the calendar year does. It’s not that kind of process. Just as a trip to Italy doesn’t end when you board the plane back to your country, this kind of journey forever changes the literary traveler. As Govinnage, Bradford, and Morgan too have discovered, these colors become part of us. This experience has given me clarity and direction as a writer. It’s sparked a new appreciation for translation. It also fills me with awe as I ponder the rainbow of stories ahead.