Sects, Cults, and Heretical Messiahs: Raoul Vaneigem’s Resistance to Christianity

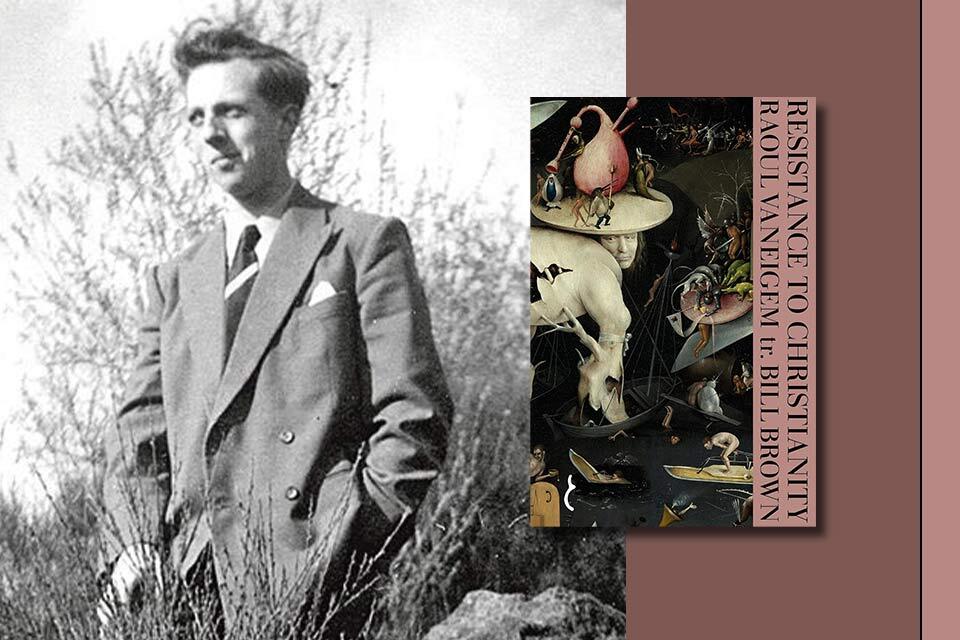

With its stunning wraparound cover, featuring a detail from Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, this edition of Raoul Vaneigem’s landmark Resistance to Christianity: A Chronological Encyclopaedia of Heresy from the Beginning to the Eighteenth Century, translated by Bill Brown (ERIS, 2023), is beautifully produced and, indeed, encyclopedic, presenting the full panoply of heresies that defied the Catholic Church, with evenhanded clarity and thoroughness.

With its stunning wraparound cover, featuring a detail from Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, this edition of Raoul Vaneigem’s landmark Resistance to Christianity: A Chronological Encyclopaedia of Heresy from the Beginning to the Eighteenth Century, translated by Bill Brown (ERIS, 2023), is beautifully produced and, indeed, encyclopedic, presenting the full panoply of heresies that defied the Catholic Church, with evenhanded clarity and thoroughness.

Vaneigem, born in 1934, is the second-best-known member of the radical group Situationist International (1957–72). His Treatise on Living for the Use of the Young, clumsily published as The Revolution of Everyday Life (1967), is the second-best-known SI work. First-place honors go to Guy Debord and his Society of the Spectacle (1967). In addition to the many centuries covered in Resistance to Christianity, another book by Vaneigem, published in 1986, focused on a single heresy. The Movement of the Free Spirit (1986) illuminated its subject, that anti-authoritarian, nature-oriented, millenarian strain from the thirteenth to seventeenth centuries in Europe. The book before us deals with heresies radical in some ways, and heresies mainly repressive. The topic itself, especially that of egalitarian, apocalyptic medieval heresies, attracted notice from a curious source—Norman Cohn’s The Pursuit of the Millennium, available in French translation as of 1962—curious in the sense that Cohn’s interest was anything but sympathetic to such movements. However, his book was popular and drew attention to the substantial but overlooked radical currents of the Middle Ages.

Vaneigem’s catalog of clashing elements begins far earlier than that. His discussion of Jewish diasporas and Judean sects such as the Sadducees involve phenomena that predate the Christian era by hundreds of years. A long-term development, it was the traditions and culture of the Essenes that originally constituted Christianity. The latter, according to Vaneigem, “is nothing other than the entirety of the Essene sects, encompassed by the general term Judeo-Christianity, and set in opposition to the Pharisees.” Among the Essenes, or Men of the Community, were their own splits and schisms as the new religion gradually became a more or less fully Hellenized, de-Judaicized Christianity.

Sects, cults, and messiahs were plentiful before Jesus, and in the Christian era his nature and church were up for grabs for centuries. Drastically different interpretations clashed for supremacy, while various prophets and apostles vied for influence over the years. Unheralded today, it was the anti-Judaic missionary Marcion, according to Vaneigem, whose work established the Catholic Church. The four New Testament gospels, a universalist credo, headquarters in Rome, all were established by the business-oriented Marcion. Ending up an excommunicated heretic, his influence was, and is, profound.

Sects, cults, and messiahs were plentiful before Jesus, and in the Christian era his nature and church were up for grabs for centuries.

In the second century, the New Prophecy was an ascetic millenarianism with a taste for martyrdom. It emphasized faith over the dualistic Gnosticism and the knowledge favored by Gnostics. Already there were many other less well-known countercurrents against the Church of Rome as it extended its authority, ordered and harmonized the various acts, letters, and gospels. Vaneigem assiduously tells the stories of numerous rival Christianities. At times the countercurrents involved whole communities. Chapter 17, “Three Local Communities: Edessa and Bardaisan, Alexandria and Origen, Antioch and Paul of Sanosata,” explores rival churches and their prominent orthodox spokesmen.

The Council of Nicaea, convened in 325 ce on the orders of Roman emperor Constantine, “marked the official birth of orthodoxy and, consequently, of heresy.” By laying down the law of Church dogma, Constantine added the backbone of increasingly popular Christianity to the waning power of imperial Rome. The consecrated Nicene Creed rendered dissenting views heretical by definition. In the next century, Pelagius challenged Bishop Augustine of Hippo, asserting the individual’s capacity to attain grace beyond the role of the Church. Augustine defeated this heresy, and the Church was further empowered with the requirement of baptism.

By laying down the law of Church dogma, Constantine added the backbone of increasingly popular Christianity to the waning power of imperial Rome.

Later in the first millennium, the Bogomils of Bulgaria rejected church and state along with most of the articles of faith and hierarchy. A Gnostic-oriented anti-authoritarian theory and practice dependent on individual spiritual autonomy, the Bogomils flourished in the Balkans for centuries. An offshoot of the Bogomils in the west, Catharism’s severe moralism provided a reformist appeal for many, especially in eleventh- and twelfth-century France. Also known as the Albigensians, these heretics embodied a regressive, anti-nature stance.

Waldensians, Beghards and Beguines, Flagellants, Picards, Anabaptists, Millenarians, and countless others who resisted the Church appear in the book’s richly rendered forty-eight chapters. Among them, the Brethren of the Free Spirit, to whom Vaneigem devoted a separate work, were indeed about freedom, in maximum measure, for women as well as men.

This survey ends at the time of the French Revolution, after which Christianity’s power declines across the board. An epoch begins to dissolve, the context of the study coming to an end. In 2022 Vaneigem provided a forward-looking afterword that concludes with these lines:

Commercial civilization is toppling over into nothingness, but it also understands that its fragility will not be able to drag us down with it. We have in us and for us a world in which the will to live is everywhere spreading its blazing unrest. The radicalism of some is enough to annihilate the alienation of a great many people. Because if stupidity is contagious, intelligence is empathetic. The former wastes away; the latter is reborn and shines out. The imposture of the Gods and masters no longer obscures the era of the creators. To allow renatured freedoms to govern us is to protect ourselves from all forms of government. We only dream of life and its festivals—let’s make them real!

Eugene, Oregon