Poems of Recollection: Kimberly Blaeser’s Copper Yearning

Manoomin. It is the first Ojibwe word I will learn. It means wild rice, or “food that grows on water.” The sound of it is fitting. Less sibilant than rice. A water word.

Mikwendan. Remember. Mashkiki. Medicine. Dibaajimowin. Story.

Kimberly Blaeser’s Copper Yearning (Holy Cow Press, 2020) has few footnotes and no glossary for the many Ojibwe words scattered through her poetry. My copy of the book, therefore, is full of my own handwriting, painstakingly translating what my impatient brain would rather infer. I click the little speaker icon from The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary to hear the ancient words spoken slowly. A language that takes its time. Sometimes the meaning of the word is revealed in later lines, but often it is the key that unlocks the meaning of the poem, and I must do the work to find it. She does not hold my hand. Niigaanii. She leads. Ogichidaakwe. Ceremonial headwoman.

Miigwechiwi. Thanks, gratitude.

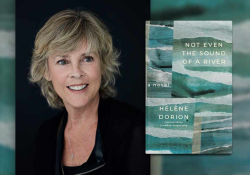

Kimberly Blaeser is, among many other things, an Anishinaabe poet, essayist, photographer, and professor at UW–Milwaukee. Her poetry has been widely translated, and her photographs and picto-poems have been featured in various art exhibits (see “Captivity,” WLT, May 2017). This is her fourth volume of poetry, a collection that explores the persistence of ancient ways in the face of the determined erasure of indigenous cultures and voices over the centuries.

What Blaeser has to offer is a bitter medicine.

I opened Copper Yearning looking for familiarity, comfort, and escape. Wisconsin, in my mind and memory, was my grandmother’s state; I had lived with her for several years, and she recently passed away. I wanted to read of the glacial bluffs surrounding Devil’s Lake, the mossy stones, the river birches. They were all there as I remembered them but with new, ancient names. Wiigwaasikaa. There are many birches. Ajijaak. Sandhill crane. The geography, the animal life was the same. But Blaeser is not terribly interested in my comfort, familiarity, and escape. What she has to offer is a bitter medicine. Her world is one of Thunderbirds, underwater panthers, Jingle-dresses, and healing songs treating deep ancestral wounds. Facts, dates, and statistics I vaguely recall from grade school are given faces, or buffalo bodies. History is demythologized when spoken from the “medicine pouch” of her voice. The present is depicted in all its frightening, ugly truth, in its stark contrast to peaceful days spent in the poet’s kayak among the cattails, or beneath the ricing moon. In her work, “echoes of old songs / shorten and grow / into poems / of recollection.”

In the poetry detailing Blaeser’s experiences in the northern forests and lake country, and those of her Anishinaabe people, she offers a haunting account of the Chippewa Trail of Tears. There is an interjection of notes from a nun on the unsuitability of reservation housing for fostering orphans. “We call them cousins,” Blaeser corrects, having grown up on the reservation herself. There is an ode to Cassius Clay, for teaching her to stay off the ropes because “nobody’s going to stop this fight and no one goes down easy here.” There are, chillingly, poems depicting the police brutality shown at Standing Rock. “When We Sing of Might” depicts teenagers hiding from the cops, “firecrackers our only sin,” and “arrestable moments could go either way […] when they are the wrong color / when their pockets are empty / when liberty and justice for all—is all used up.”

There are also celebrations and moments of surprising levity.

But there are also celebrations and moments of surprising levity. At about the midway point of the book, “Exit #135” is a playful intermission, an ode to a Cracker Barrel and all its chintzy Americana, a reminder that this, too, is her America: ”I’m kicking off my shoes and taking a seat.” The poems from this section, “Alchemy Inherited,” are my personal favorites, with so many dog-eared in succession that my book no longer quite lies flat. They describe the poet’s convergence of her many selves, her seeming contradictions, an effortless drifting between ancestry, memory, presence, and, as “Exit #135” concludes:

I am a walking butter churn, a contradiction in terms, or the future perfect tense:

We will have been feasting of the forbidden fruit for years on end.

Copper Yearning does what only poetry can do. It puts us so deeply in the perspective of the poet that every line which connects us resonates with a profundity that borders on the sacred, and every line that divides us is uncomfortable in its discordance, a chord we need to resolve. Truly powerful art is not afraid to make its audience uncomfortable, nor does it feel the need to offer resolutions. It demands engagement, and in this way, Blaeser’s poems are radical.

Norman, Oklahoma