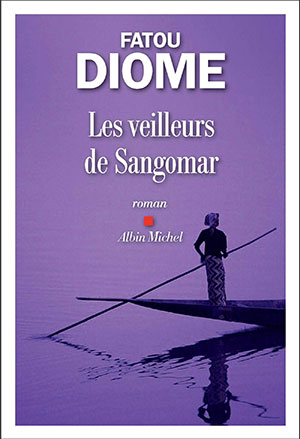

Les veilleurs de Sangomar by Fatou Diome

Paris. Albin Michel. 2019. 336 pages.

Paris. Albin Michel. 2019. 336 pages.

SENEGALESE AUTHOR Fatou Diome’s latest novel, Les veilleurs de Sangomar (The watchmen of Sangomar), plunges the reader into young Senegalese widow Coumba’s period of grief and official mourning after her husband’s death in the 2002 Joola shipwreck, a real-life catastrophe.

Diome skillfully expands Coumba’s story to France, where relatives of another Joola victim, Pauline, endure their own loss. The plot intricately choreographs the two sets of mourners’ steps, as Pauline’s parents visit Senegal to track their dead daughter’s last movements. This dense portrait of human love and suffering thus incorporates the story of Pauline’s migration and interracial marriage.

Notably, indeed, through Coumba’s story, Veilleurs recontextualizes Diome’s trademark migration themes in ways that richly demonstrate the metaphoric power of actual migration. Coumba is a reenvisaging of Diome’s lone questing migrant woman to France, the outsider struggling to connect with a foreign society, found most memorably in Impossible de Grandir (Impossible to grow up). Like these “true” migrants, Coumba is burdened by memories of her old life, which impede her progress, but is also enticed by the allure of new thresholds. The push and pull—is this Derrida’s “hostipitality”?—of the spirit world, and of Coumba’s new world of widowhood, are Veilleurs’s subtle allotropes of the dynamic facing migrants from Senegal to France, or anywhere else.

Coumba is also an artist figure, like other Diomien migrant women. Her nocturnal writing sessions show that art heals wounds and promotes the autonomy important to this Muslim widow resisting her husband’s family’s desire to control her future: “Une fois sa résolution prise, elle se sentit capitaine dans sa barque” (Her resolution [to write], once taken, made her feel like captain of her own vessel).

Diome-watchers will also find many of the author’s favorite stylistic devices: long stretches of narrative exhortation, questioning, and exclamation, which often need a firmer editorial hand to avoid diffusing the author’s focus and blunting her purpose. Nor has the author lost her taste for periodic narrative sermons on race, religion, and sexism. But Diome’s intricate characterization of Coumba remains the magnetic center of the novel. She is not merely a new widow but also mother to her baby daughter, and a daughter to her own mother, whose loving care for her bereft daughter typifies the matrilineal strengths of the Sérère culture on the Senegalese coast, where a shipwreck triggered not only personal, but national, grief.

Rosemary Haskell

Elon University