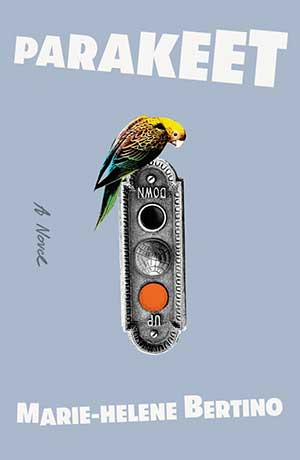

Parakeet by Marie-Helene Bertino

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2020. 240 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2020. 240 pages.

FOUR DAYS BEFORE HER wedding to an elementary school principal, our protagonist, known only as the bride, is confronted by her grandmother, in the form of a parakeet, who tells her to find her estranged brother, a reclusive playwright who made his name writing one of the worst moments of his sister’s life. Once found, her brother confides that she has transitioned and goes by the name of Si-mone. The pair, over the next few days, find their way back to each other as sisters. All the while, the bride’s wedding plans fall down—literally—around them.

Marie-Helene Bertino’s second novel, Parakeet, is a weird, ultimately uplifting journey, equal parts whimsy and wisdom. She draws in her audience with eccentricity and levels them with devastating, relatable, human thoughts. She makes readers vulnerable, more connected, laughing along the way. Her razor-sharp, observant eye re-creates ultraspecific details and thoroughly rounded characters through the strength of her skill on the level of the sentence.

The magic in Bertino’s writing comes when her individually laudable sentences are pieced together like a mosaic. Her choices are purposeful, meticulous even, but the effect is delightful, seamless, and unexpected. She includes unique images that do double work for the novel: not only do they advance plot, but they also serve to more deeply expand our understanding of the characters. Every line works with those around it to evoke a deliberate picture and feeling. Her avian word choices (“perched”; “my heart beats solid in its cage”; “I hold my sister’s hand, a small, precious bird”) bring us back repeatedly to the catalyst of the story in subtle ways. She masters both lateral and vertical movement within the same paragraph, especially at the ends of the chapters, by juxtaposing her lines, both grounding us in the physical images and elevating us to higher thought simultaneously.

Bertino has a tendency to subvert readers’ expectations at every turn. She breaks convention by including one chapter from Simone’s point of view, when the rest of the novel is written from the bride’s. Here, Simone has a chance to tell her own story, in her own words, about her transition and life. The heartbeat of the novel lies in the budding reconnection between the sisters, who, up to this point, operated on a scorched-earth policy. The resolution of the climax is both inevitable and surprising, adjectives Bertino garners from the very beginning.

Taylor Hickney

New York