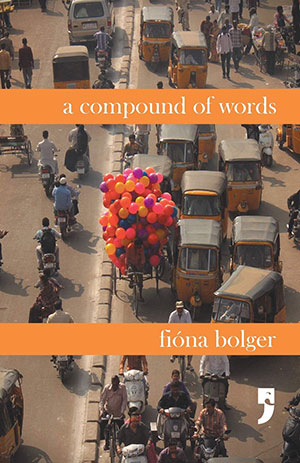

A Compound of Words by Fióna Bolger

New Delhi. Yoda Press. 2019. 106 pages.

New Delhi. Yoda Press. 2019. 106 pages.

THE IRISH HELD a distinctive position in the British Empire. They were colonized by Britain but were also its accessory to empire in India—to the extent that they produced the Viceroy of India, Lord Dufferin, as well as Brigadier John Nicholson, alias “the butcher of Delhi.” Fióna Bolger has written a collection of poems that soars from this position to occupy a unique hybridity, which expands Homi K. Bhabha’s concept of in-betweenness with consummate ease. She fashions herself as a writer between borders and so explores the multiplicity of contemporary India in her wide travels, engaging with great felicity the Sanskrit, Dravidian, and Persianate cultures of India alongside her Gaelic inheritance.

In the titular poem, she exhibits the rich diversity she brings to her poetry, putting together words of Asian and European etymology with the greatest confidence to invite the reader to break their linguistic shackles. The Irish wajalukinat is placed alongside the Sanskrit philosophic maya and juxtaposed with a contemporary cuss word from Hindi, saala, which “must do penance” with the Tamil and Irish slang of “aadivanga knee as you cruise for a bruise”; when “crushed together,” she writes, “we make juice.” “Juice” can be one of the translations for the Sanskrit-derived word rasa, which also means flavor and has given birth to the Rasa theory of poetics/aesthetics.

What Bolger thus achieves in the collection is a cartography in verse of India’s rich diversity, with a focus not only on language (as well as India’s many gastronomic and olfactory delights) but also its present problems of violence, particularly against women. She has attuned herself acutely to various local cultural and aesthetic registers and fashions herself as a Rasika (from Sanskrit), an aesthete or critic particularly of music but also possibly of all the arts. While speaking somewhat tentatively of grappling with food and masalas in the first two “Rasika” poems, by the third, the poet-narrator is a masterful Indic aesthete. She’s become a “conjuror of connections / gatherer of friends / Rasika of life.”

A strong feminist urge is combined with nuanced cultural familiarization. She goes to local women saints for inspiration, such as the Kannada poet-saint Mahadeviyakka; or the Kashmiri poet-saint Lal Ded and her vakhs (spoken poems) to exclaim how “The rope is tightening fast, the distance between thoughts / a breath—” Elsewhere, she adopts the Kashmiri/Persian/Urdu form of the ghazal to write of militarized Kashmir. The first is on disappearances: “where have you hidden my new crescent moon? I search for my son by the light of the moon.” While here she is concerned with the plight of Kashmiri mothers whose sons are missing; in the next “Ghazal for a Kashmiri Girl,” the locals helplessly “question her honour. Out / of bound to query the soldier who / also emerged after she came out.”

The casual violence of the university and religious town of Allahabad (recently renamed Prayagraj) is narrated as well in multiple poems: “A law student beaten to death / his leg brushed against attackers.” The repeatedly assaulted, “tortured / and broken” activist, Soni Sori, “arrested in Delhi / returned to Jharkand,” asks in a poem called “Googling Soni Sori”: “Who is responsible for my condition?”

Bolger is a truth-seeker in India’s underbelly, when in “Sathya Sutra” (the thread of truth) she claims: “I know the truth of genocide / is not in the numbers / raped or murdered or displaced / each swollen body is a stitch / in the rough red fabric / part of the whole.” She’s been to “Kollam” and savored “The Malayali Moon,” but she has also witnessed the rampant violence jostling with spices in India for its own smell. She has combined classical and medieval Indian learning with Gaelic humor and mysticism, and all with globalized and localized colloquialisms, in her sharp (refreshingly political) verse. She then returns, “Wapas,” to her “snow silenced world” in Ireland as the collection comes to a close. In the penultimate poem, she exclaims: “A foreigner is someone who makes us feel we belong” and concludes, with some hiraeth, that she is “always returning”: “Desi or pardesi / immigrant or emigrant / indigenous or disingenuous / pretending or blending / deceiving or conceiving / another way, elsewhere / anywhere, but here.”

Maaz Bin Bilal

Jindal Global University