The Psychoanalyst’s Wife (an excerpt)

Looking for her dead wife, a woman finds an unusual bonsai with mythical connections and a few complaints.

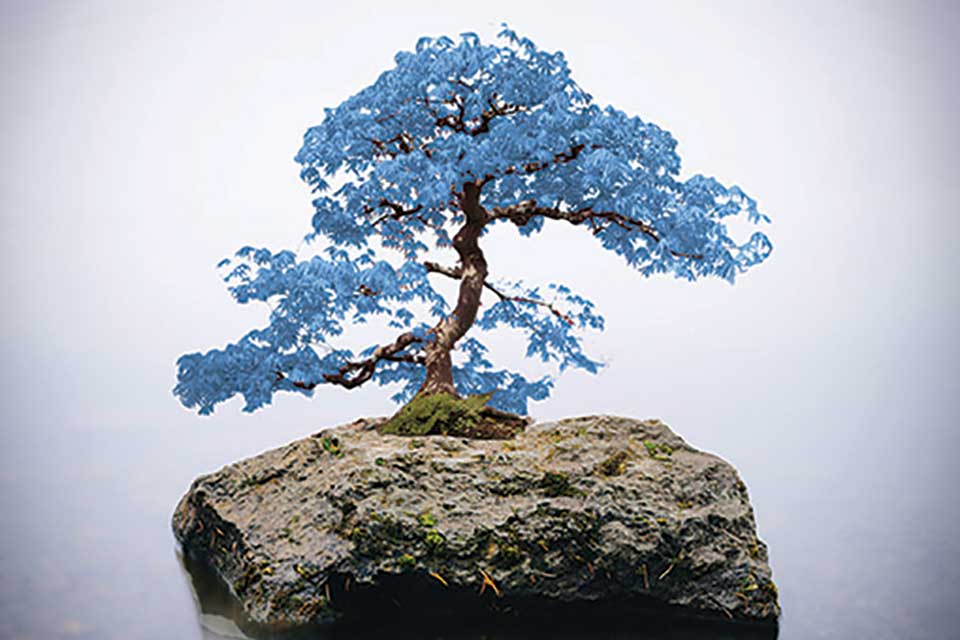

Laurel, without shoes, wandered aimlessly from one end of the river to the foot of the mountain. On the seventh day, her blue blouse is torn, her skirt tattered, and her hair disheveled. Her patience thrives on a tight leash. By the twelfth day of her search as she squats on the edge of the river, cups her hands to gather water into her mouth, she notices motes of blue in the far distance. She abandons the river and walks toward the luminosity of the distance’s lambent, refulgent azulness. The departure from the river inescapably draws her to the blue ghost maple bonsai whose blue sea leaves float like a multilayered ruffle skirt. The enigmatic bonsai sits contentedly on the rock as if not born there but on display like a sculpture at a museum, using the rock as a makeshift white cube box. Without understanding why, she finds herself clearing her throat. But the body understands what it must do before the mind finds its logic. For days, Laurel has beseeched the sky, the earth, a piece of log, an animal of the sky, and even an alligator, and her voice has gone hoarse from begging and asking and searching. Her voice for many days has been her primary sonic flashlight, and now it’s so dim a deer could easily mistake her mouth for one lame scale on the slimy body of a feeble fish. When her voice fades completely, without the electrochemical cell of her vocal cord, what will she do? What will she do when her aural battery is dead?

But the body understands what it must do before the mind finds its logic.

In her small, faint voice, she probes the bonsai tree: “My wife recently committed suicide. Do you know where she is? Has she drowned in the river? Has she hung herself from a tree? Did she jump off the cliff? Could you please tell me where she is? I have been searching for her for days . . .” Laurel’s voice trails off. There is no echo. No sound. She sits down forlornly on the adjacent, crooked rock. She stares at her bony arms and into the far distance. She can’t recall where she placed her flask of water. Neglectful of her body and its twin environ, she appears emaciated. She may have forgotten to eat like the way the earth forgets to consume rain. Beyond the bonsai is the blue expanse of the sky, semigray, semifoggy. It seems as if the sky has woken up from a dream, and it yawns at her. Laurel thinks this is the only way to explain the sudden eggshell whiteness that imbues the dark room of her imagination. It isn’t just her imagination, but the sky itself. She tries to pull herself out of her own reverie, but the force of forlornness draws her back inside her own mind.

If only I could find my wife’s body, Laurel thinks to herself. She is no detective. Being a psychoanalyst hasn’t helped her at all in the search. She wishes she did her dissertation on something more useful like being a geologist or ecologist. The earth doesn’t possess a psyche. Or does it? Could she probe the consciousness of the cosmos? Could she recline the earth on a sofa and hypnotize it in a way that caused it to reveal the whereabouts of her wife? Has she confused psychoanalysis for telepathy? Laurel begins to sob quietly. But something in the immediate distance halts her from her own despair.

She is no detective. Being a psychoanalyst hasn’t helped her at all in the search.

“Tis a shame to waste such a tear on the air.”

Laurel turns her head and inspects the source of the voice. From her peripheral vision, she can see the cobalt bonsai blinking. As if begging to be touched, she reaches out and runs her soiled hand across its sea-blue leaves, and the dwarfed tree, inadvertently, speaks. Laurel withdraws her hand immediately.

“Why are you touching me?”

“You startled me. I did not know you could speak.”

“I am alive therefore I should speak.”

“Not all things alive could make sound.”

“But why did you touch me?”

“You were blinking and it caught my attention. Were you trying to get rid of an errant eyelash?”

“You mean an ant?”

“Or a caterpillar.”

“I blinked because I think I hear a well dripping water.”

“There is no well here.”

“Are you the well that drips water?”

“If you say so.”

“Would it be too much to ask if I could have a sip. I am so thirsty.”

“Why didn’t you ask sooner?”

Laurel stands up. She gathers herself together in preparation to walk toward the river to retrieve some water for the dehydrated bonsai.

“Where are you going?”

“I’m going to the river to hydrate you.”

“No. Please. Cry on me.”

“I don’t have any tears left. It won’t be enough, and you will soon be thirsty again.”

“I only need one tear to un-thirst me.”

“That seems so impractical.”

“Now, please cry on me.”

“I can’t.”

“I know you are not a faucet. I turn a knob on you in a certain direction and out you come, but what will help you cry?”

“My wife.”

“Your wife?”

“She self-euthanized.”

“How do you know? Most dead people don’t self-announce their nonexistence.”

“I feel it in my gut. Whenever she is gone, I feel it.”

“Your gut?”

“Like your roots.”

“I see.”

“Try to cry on me, at least.”

“Just one tear, you say?”

“Yes, just one.”

Laurel thinks of the first time she tried to convince her wife not to kill herself. And she recalls how unsuccessful she was. A drop of tear clings on the edge of her eyelash. She bends over and the tear falls onto the sea blue of the bonsai like a caterpillar falling off the branch of a tree. The dwarfed bonsai is not an ordinary tree. The tear, upon immediate landing, unlocks the consciousness of its branches, roots, and trunk. In one swift transformation, the bonsai has turned into the doppelgänger of the nymph Daphne. She is the daughter of the river god, Peneus of Thessaly. Years ago, the god Apollo was cursed to fall in love with her. To escape from being forced to have sex against her will, she begged her father, Peneus, to save her. He responded by turning her into a laurel tree. And over the years, the laurel tree becomes a bonsai. Her father, Peneus, told her that only the tear, one drop, of a woman named Laurel could turn her back into a nymph. She would return into another version of herself, but not her original Daphne self.

“Have you ever been transformed before?”

In her female form, the tree speaks gleefully: “Have you ever been transformed before? I still remember my father transforming me. My new arboreal garment. The wooden structure paralyzed and then petrified my legs. Strips of bark entombed my skin, mouth, and breath. My breasts became lumps of wood. My hair was leafy, stemmy, and verdant and massively ecofriendly. My hands, oh my hands, became perennial and herbaceous. Cageless, I used to dance and frolic freely, but then I stood still for millennia. I became a coeval relic of history. And I became so poisonous. My ovaries and my berries, in particular. No one dares to eat me, but they do. They grab at my ovaries as if they are edible diamonds. Oh, how I resented these noncannibal cannibals!”

Las Vegas, Nevada