#PuertoRicoRises

After Hurricane Maria, in a hospital with no electrical power, a man seeks medical treatment for his father as the US president visits the city.

“Papi ain’t feeling well. Come home when you can.” The original message was received on the night of October 2nd, but since the cellphone towers were down, I got it on the morning of the 3rd. On that day, I got up around six, with the morning heat relentlessly attacking due to lack of electric power. After brewing coffee on a camping burner, I went to the supermarket at Ciudadela before opening time, at eight o’clock. During the time I allowed myself for drinking coffee, I listened to my portable radio: the entire country still had no power, water came and went from the pipes, people accumulated debris in front of their houses, there was still no access to rural roads, the government was still bunkered at the Convention Center in Condado, and all they said was that the Americans would be coming soon, that there were enough supplies for everyone but they’re running late, that provisions are at the docks and they’re coming, that Puerto Rico will rise again, #PuertoRicoSeLevanta, said the hashtag in Spanish. Among the calls from people from our “diaspora” desperately asking if their relatives are okay, journalists just wouldn’t stop repeating that today the president would be visiting. Got no time for that shit, I thought, while I took the empty cup to the sink, prepared my reusable bags, and fled down Antonsanti Street to the supermarket.

I got the message upon exiting the store. A “Puñeta!” escaped from my lips at a not-so-loud tone, yet enough to get some looks by those nearby. My mind went blank. It took me a few minutes to calm down. Daddy was doing fine yesterday, although he complained of pain in his knee, which had looked quite swollen. But the old man is a stoic Spartan and had self-diagnosed cellulitis, to be controlled by taking two Tylenols and putting in some sleep. He would be feeling like a tank in no time. Shit. To think I was happy because this time the line to get into the store wasn’t that long, that today they had let the people in twenty at a time, instead of ten, that today the undercover security guards did not follow me to see if I would hide something under my clothes. Today was pointing to a normalcy that this text message just destroyed. Oh, what the hell. I walked home as quick as possible so I could head to my parents’ house.

Part of the shock after the storm was feeling how gas generators had damaged the sky.

Coming down the Parada 26 slope, toward the Sagrado Corazón station, the wind finally blew a little. It camouflaged the heat but not the smell of fumes emanating from power generators. Part of the shock after the storm was feeling how gas generators had damaged the sky. I was traveling on my bike because my car had no gas, the lines at the stations ran up for miles, and the train and buses were not working. I also needed the exercise to flatten my belly and to clear my mind on the way to Río Piedras. I was carrying a bag full of bread, tuna cans, some root vegetables, and boxed milk. My parents are not healthy enough to do the groceries. Not in these days, anyway. Between her diabetes and obesity and his frail heart, they could not handle hours standing in line nor the hassle at the checkout registers. To do the groceries, you had to put up with over an hour wait at the ATM line because the credit-card payment system was still down, and then another couple of hours at another line to enter the supermarket. Only I could handle this fuckery. I went to the ATM at night and withdrew some money, then I went to Ciudadela every couple of days to buy food for a day or two. I could not stay with my folks because I was afraid someone could break into my apartment and because their chronic conditions could cause me to have an anxiety attack.

As I passed by the bridge over the Martín Peña Channel, I started seeing the lines at the gas stations along Ponce de León Avenue. I rode in the bus lane because it’s the safest way to travel on a bike. The Shell station over Mercantil Plaza was booming with people. Among the car line blocking the entire right lane and the line of people with gas containers to feed generators, they could easily spend the entire day waiting. There was no one at the gas pumps, and there was no movement at the exit or at the convenience store—the station had no gas supply, and they were waiting for the truck, which was supposed to come at a given point during the day. A few blocks down at the Total station in front of the Popular Center, things were the same. There were two squad cars and national guard soldiers overseeing gas distribution. I rode by the Milla de Oro until the San Juan courthouse. Several police officers directed traffic at the main intersections—Roosevelt Avenue, Ponce de León Avenue, Gayama Street, Mayagüez Street. Once I cleared all the gas stations, there was barely any traffic. People were staying home. I couldn’t remember how much gas was left on mom’s car.

Once I cleared all the gas stations, there was barely any traffic. People were staying home.

Every bike ride to my folks was a recon expedition for damages that we were still unable to believe. The air was still dense and reeked of humidity, fuel, and rotten meat. We were unable to overcome this phase of shock. Destruction began from the broken glass windows at the Ciudadela complex, then went on to counting the fallen trees, many of them cut into pieces and placed in front of houses and businesses. You could not forget the fallen utility poles of every size and shape, the fallen signs, the broken traffic lights. Not a single one of them was still standing; everything had fallen or was damaged.

The first thing I saw when I stooped the bike in front of my parents’ house was my dad sitting at the balcony, face down, his shoulders over his knees. Mami came out with a wet towel and placed it over his shoulders. His right knee was red and swollen, and he made that face that said he was not doing so good, when the blood does not reach where it must go.

I put on a pair of pants that did not fit him anymore so I could enter the hospital without any problems. I helped Papi up. He complained greatly as he walked, barely able to move his right leg and carry it forward. I knew that the situation regarding his heart was not urgent because he was not coughing much and because his face had not lost any color. For now. Besides, he wanted to walk by himself, although it took him almost an hour to bathe and get dressed. Once he came out to the balcony, I took the car keys and, little by little, said goodbye to my mother—“May God help you, be safe”—and put him in the car.

While my father was taking a shower to cool off before the trip to the hospital, Air Force Once was touching down at the Muñiz Air Base. After exiting the plane escorted by the resident commissioner and a group of assistants, the president greeted the governor and his wife then walked to a hangar for a press conference. He was greeted by the leaders of the legislative branch, some mayors, and local cabinet members. The first thing this orange man who commands the US did was to congratulate Brock and Elaine for their work—unbelievable job—just like that, no last names, as if he were in a therapy group or something; oh, well, you know, thank you for your effort after a category five storm. The next step he took was congratulating Tom, the FEMA regional coordinator, and later praising the work—great stuff—by General Buchanan, in charge of the US Army in Puerto Rico. The Governor was next in the line of greetings, yet the Trumper did not call him by name nor his last name, only by his political office, Governor, although he did highlight that Rosselló was from “the other team” and that he did not play politics. At least there was a handshake. The resident commissioner was treated completely the opposite; she was mentioned by her full name, Jennifer González Colón, and her political rank, followed by generous praise for her role during the emergency. Greetings moved on to Linda McMahon, federal administrator in charge of overseeing small businesses, and also co-owner of the largest American entertainment company, the WWE—yeah, the wrestling people. Nick was next, federal budget coordinator, followed by a comment stating that the island had affected the federal budget—a bit out of whack—but everything was fine, because this was not a real catastrophe like Katrina, because the official death count was barely 16 or 17 after Maria, compared to the over a thousand dead after the Louisiana hurricane—literally thousands. While the prez completed his greeting session, the Governor took selfies, making sure that the US Commander in Chief appeared in the frame.

While the prez completed his greeting session, the governor took selfies, making sure that the US commander in chief appeared in the frame.

When we were ready to go, my father’s face began to change. I blasted the air conditioner because this would be good for him. As we passed the housing projects to enter Piñero Avenue, Trump was commending the work of the US Navy—very big stuff. Traffic was a bit light because there were no traffic signals, but it was not heavy. Or so I thought, until the intersection with the university campus and then up to Pepín bakery. From then on, traffic began to grow heavier, because we were approaching the exit to Old San Juan and Highway 22. “Fuck,” I said, losing control. I knew the prez was supposed to travel through Highway 26 and then to Highway 22 up to Guaynabo, so those roads would be closed, but I was not going in that direction. Dammit, but I didn’t count on the fact that, since the two main highways in San Juan were closed, people had nowhere to go, and so all traffic would be diverted to Highway 18, which, indeed, was our route. And just then Papi began to lean forward and to touch his chest constantly. While my old man tried to tell me with a broken voice that “I just don’t feel well,” Trump glorified the coast guard commander—the real Coast Guard—the air force general in charge of Customs and Border Patrol, the DOE chief, and Scott, some EPA assistant. While my father managed to recline his seat back in order to breathe better, Señor Trump recapped his greetings and said that, although he knew that the local political elite was present, he did not have any more time for protocolary meet and greet, that he had other things to do.

As the SUVs escorted the presidential convoy along Highway 22, on the way to Muñoz Rivera urban housing project, I tried recklessly to make my way among the cars, looking for a way forward. I was driving mom’s compact Mitsubishi, and the jam was mostly toward the San Juan exit, not toward the opposite direction, the Ponce exit, the one I needed to get on to reach the hospital. And so, I gradually formed my way using any inch of space we could fit in. I started banging the horn to see if others would let me pass, but the road was quite jammed. It took me half an hour to travel through a section that usually takes no more than five minutes, and I was finally free. There was not a single police car nor ambulance nor official vehicle in sight. By then, Trumpo had reached Calvary Chapel church with his entourage, located at a small shopping mall whose owners were good citizens, especially when they opened their wallets to the governor during the election campaign.

And then the damn gas light turns on. I tried to gather all my strength to not lose control of the car or myself. I asked the old man—“How we doing?” It was clear to me that he’s had better days, but I’ve seen him look worse, like the time he entered the Emergency Room with his life on the line and came out with a three-cable pacemaker. Papi realized that I was getting nervous and tried to calm me down with a—“Take it easy, I can make it.” I finally got on Highway 18 while Señor Trump was strolling by the church’s nave—a lot of love in this room—full of fans that had shown up just to quench their curiosity. At the traffic light at the San Juan Cardiovascular Center entrance, there was a bit of a jam, but not due to the lack of power but because of a crash between an ambulance and a pickup truck, probably because there was no one to control traffic. I went by on the left, at risk of being stopped by the police or being met by another car head on, but there were no officers. Once I crossed Américo Miranda Avenue, not without evading two vehicles at full speed, and honking and cursing all drivers to hell, the car definitively ran out of gas at the very corner of the hospital entrance, less than a block away.

Just when the orange president was throwing rolls of paper towels to the Puerto Rican public, much like an NBA star, the security guard at the ER stopped us.

I got out of the car without thinking much and opened the passenger door. Papi had managed to sit up, a good sign. He tried to get up on his own but instead went backward, though he didn’t fall on his back because I caught him just in time. As I tried to put his arm over my shoulder, he moaned in pain. He could barely move his back and knee, which was swelling even more as time passed. A paleness started to set in on his face. I gathered my thoughts again—I gotta hustle. I didn’t have to scream for help because I felt an additional sets of hands supporting my shoulders. I turned as I could, ready for a fight, but I immediately let my guard down. It was two youngsters who were on their way to pick up their abuela because the hospital was about to shut down—they were almost out of diesel and there was no way to fuel the generators. “All right, man. Whatcha need?” one of them said. I made sure they held Papi securely for a moment, then quickly turned on the hazard lights and locked the doors. Between the three of us, we formed a rescue seat with our arms and carried my father the entire three hundred yards left from my car to the Emergency Room door.

Just when the orange president was throwing rolls of paper towels to the Puerto Rican public, much like an NBA star, the security guard at the ER stopped us.

“You can’t come in.”

Before the guy said anything else, one of the youngsters pushed him out of the way, opened the automatic doors, and went back to using his arms in the rescue chair. There were about fifteen people in the small waiting room, almost entirely patients. As I looked left toward the beds and the nurse station, a doctor wearing plain clothes and a stethoscope around his neck came out. He advanced toward me with a reprimanding face, but when he realized the size of my companions, he held back. “All right, come in, sit him down over here. I’ll be there in a moment.” I turned to thank the youngsters, but they were gone. The attending physician was tending to another patient.

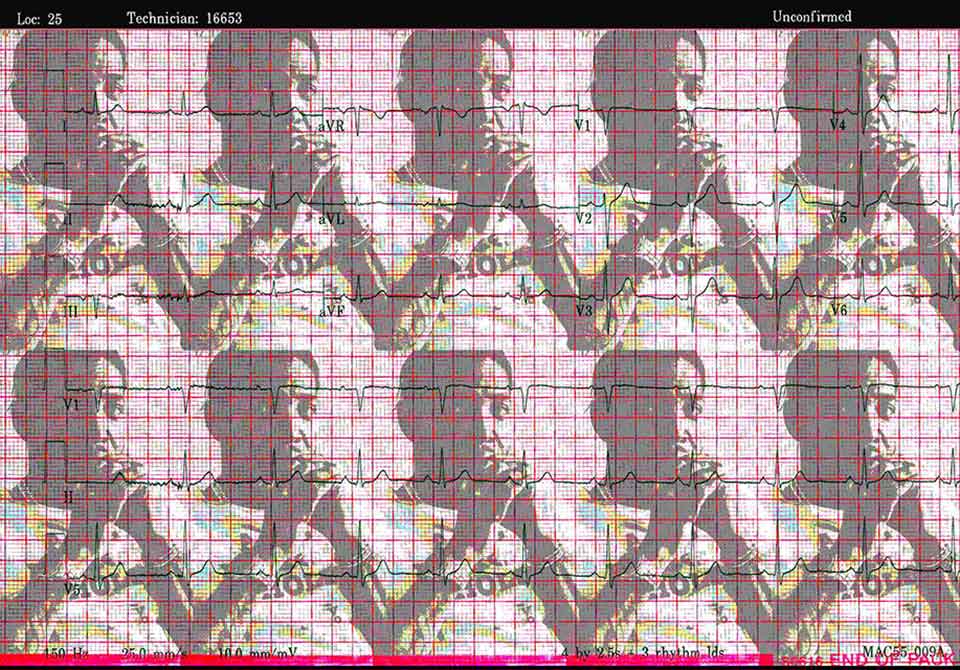

“Pulse 42, BP 90/40. What do we do, doctor? The treatment is not working. Do we prep for cardiac arrest?” a nurse asked. The doctor stopped whatever he was doing and lifted his eyes to the ceiling, then looked directly at the nurse.

“Not yet. Push ten milligrams of Midodrine and find the portable monitor. Do an echo and a sonogram—heart and right knee. Give him some Cefalexin and Metronidazole, slow drip,” he ordered without emotion. The physician turned toward the nurse station and raised his voice: “Put him on 2! Let’s go, come on!”

The medical staff stopped whatever they were doing and gently accommodated my father on the assigned bed.

“But, doctor, the patient on 9 is using the only monitor that works,” the nurse answered. The doctor walked over to the bed. The nurse followed him like a shadow. He looked at the heart monitor, as if memorizing the vital stats. He put his hand on the patient’s forehead, then felt her right cheek. Finally, he responded.

“This woman will not last the day. At least this one has a break.”

“But, doctor, the echo and sonogram machines are up at the surgery floor,” the nurse answered.

“Then I guess you have to get them ASAP,” the doctor ordered without flinching. He left the patient on bed 9 and went to bed 2. Before closing in on Papi for an examination, he took a deep sigh and told me—“Who’s this man to you?”

“He’s my dad.”

“Is he a patient here? If he is not our patient, I cannot tend to him,” he said coldly.

“His cardiologist is Dr. Borges. His office is right across the hall. But you should know that.”

“Okay, then . . . we’ll see what we can do. I’m Dr. Quiles. Does he suffer from a particular condition?”

“His heart is too big and he has a three-cable pacemaker.”

“Dilated myocardium with atrial fibrillation and hypotension. Write it down.” The shadow nurse wrote everything down in a notebook they were using as improvised medical records.

“I brought him because he’s been complaining of knee pain for a few days. It’s swollen. See? But he started feeling bad in the car.”

The doctor examined my father more thoroughly now. He felt for a pulse and used the stethoscope several times. Papi was conscious, but he had trouble breathing. Dr. Quiles felt his knee, and daddy jumped so hard that he almost fell off the bed. I almost jumped along with him. The doctor searched for a pulse on daddy’s wrist. He felt the throat, as if searching for the jugular. Then, he said:

“Nurse Rodríguez, 5 percent Linezolid drip, prepare him for a penicillin prophylaxis, just in case.” Then he looked over to address me. “Look, it seems like aggravated cellulitis. He should’ve come earlier, because, well, now there appears there are blood clots. We’re giving him antibiotics, but he needs an echo and a sonogram to see if there are any obstructed vessels. But we have no power here, and we only have one portable echo machine, but it’s being used upstairs. Since I have no way of performing a sonogram, I have to wait for the vascular surgeon to arrive to see what he can do. For now, he’s stable, but we have to monitor him.”

“So, he’s not going to die?”

“Look, I’ll be straight up with you. This should be a normal situation. You came here on time. But, goddammit, this hospital has no electric power. We cannot tend to patients properly. We’ve been ordered to evacuate. It’s better to take him somewhere else. Is your father insured? We cannot work . . .”

“Doctor! Bed 9 is crashing!” The nurse interrupted from the back.

While the doctor turned to tend to the patient on bed 9, Señor Trump was in a black SUV again, which would take him to Roosevelt Roads, the old naval base, to board USS Kearsarge. It was then when I realized that the emergency room had been working on emergency generators that did not have enough voltage to power up large monitors or machines. There were maybe five nurses running from one side to another. All fifteen beds were occupied. Each one had the drapes spread out, blocking the view of what was behind. There were three additional stretchers against the wall in the back, with what seemed to be bodies completely covered in sheets and bedding. The place smelled of hospital, you know, that strange formalin smell that sticks to your skin, yet there was also a certain stench that was not common, like a morgue. The sudden heat I felt due to lack of air conditioning confirmed my hunch. I walked up to my old man, who rested easy, yet weak. Suddenly, the doctor appeared, somewhat in a hurry, with his static face, cold, as if relaxing his face muscles would cancel all acknowledgment of life at that moment.

“Young man, I need you to wait outside.”

Before I could become pissed off and make a ruckus, two nurses and another security guard stood behind me. I didn’t want any trouble. I walked out. The waiting room was full of people now. I could not see the pushed guard anywhere, nor the youngsters who helped carry my father to care.

“They went upstairs to look for their grandmother; she’s admitted upstairs,” said a fat woman with bottleneck glasses, chemically blonde, with greasy, messy hair.

“Thanks.”

“Hey, boy, do you know how my mother’s doing? They put her on bed 9.”

“Don’t worry ma’am,” I mumbled. “They’re taking good care of everyone in there. Your mother is in good hands.”

I don’t have time for this shit. I took out my cellphone and tried to call mom. No signal of any kind. While I debated on how I was gonna move my car with no signal, Señor Trump was meeting with USVI governor Kenneth Mapp—such a great guy—aboard a destroyer. The people at the waiting would not stop talking—we have no power at home, I lost my entire terrace, at least your roof didn’t fly away, the neighbor on the corner died because she could not keep her insulin refrigerated, my friend from two streets down could not go to his dialysis session and had a heart attack, my mother got really sick and the ambulance never got there, I don’t know anything about my cousin since before the storm ’cuz she lives all the way on top of a hill in Bayamón, my mechanic’s father ran out of blood-pressure pills and collapsed on the floor . . .

At 4:05 in the afternoon, Air Force One took off from Muñiz Air Base, one hour ahead of schedule—we did great down there. I never saw anyone take a machine into the ER. A little after the presidential plane tucked away the landing gear, Dr. Quiles appeared, somewhat in a hurry, with his static face, cold, as if relaxing his face muscles would cancel all acknowledgment of life at that moment. He didn’t have to tell me anything. I knew who had flown away.

Translation from the Spanish