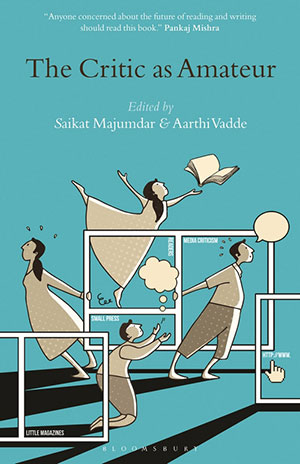

The Critic as Amateur

New York. Bloomsbury. 2019. 292 pages.

New York. Bloomsbury. 2019. 292 pages.

EACH OF THE TEN ESSAYS in this splendid, exhaustively researched, and timely collection—buoyed by the editors’ equally comprehensive introduction and a contrapuntal pedagogical epilogue on “New, Interesting, and Original: The Undergraduate as Amateur”—is substantial in developing its arguments. At a time when many can avow unashamedly that they are critics, in “Beyond Professionalism: The Pasts and Futures of Creative Criticism,” the essay that closes part 1, Peter D. McDonald asks a question that probes the marrow of the collection and provides its tentacles: “So much for the cunning passages of history. What of the future? Can creative criticism in the Tagore-Blanchot sense even be said to have one, particularly when its fate now seems tied to the embattled, increasingly corporatized, and over-professionalized university of today?”

Also in the first part, canonical critic Derek Attridge’s “In Praise of Amateurism,” aligned with the privileging of Roland Barthes’s views and Joseph North’s recent Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History throughout the book, assesses critical commentary, concluding that “instead of being driven by the need to say something ingenious and unprecedented, [it] would aim at an accurate reflection of the critic’s experience.” That is neither here nor there since, as he avers, “Doubts about literature as an academic subject produced much opposition to its acceptance as a legitimate subject for university study, and the hostilities did not end when its supporters were victorious.”

The question of whether going to university and joining its self-congratulatory safe spaces makes one a professional critic is still open, particularly at a time when gig-economy faculty are increasing. As Tom Lutz’s self-awareness is at pains to discern in “In the Shadow of the Archive,” the financial rewards of being a distinguished professor, or not, are no guarantee that the personal matters in your criticism, or that your practice will be ameliorated by the love of the amateur he prefers to professionalism. As Lutz argues, to say that everyone’s a critic does not mean that everyone writes criticism.

The three essays included under the rubric “The Critic as Amateur in Old and New Media,” the third and final part, are refreshing overviews that curb the enthusiasm about new media, especially when some of their users’ intransigence undermines the case against print media. The topics are amateur and professional exchanges in film culture, the small press and the feminist critic (in which Melanie Micir makes an excellent point that should be obvious to all stakeholders: “the vocabularies of amateurism are deployed and received differently across racial, national, and class lines”), and the recovery by Emily Bloom of radio as a medium for institutionalizing criticism in the first half of twentieth-century England.

If Bloom’s fascinating “New Judgments: Literary Criticism on Air” does not seek clairvoyance about our time, her recovery and conclusion that “here we see not the passive listener that Adorno and others describe as an outcome of mass media” is eerily timely. Based on her research in BBC archives that convincingly proves that those programs “brought together an eclectic combination of talk, dramatic dialogue, reenactment, and readings and, in so doing, formally reimagined literary criticism for a new medium,” Bloom begs the question: what will be criticism’s preferred medium after podcasts become unfashionable?

It is necessary to leave part 2 for any closing statements because, despite the editors’ valiant efforts throughout to reveal and contextualize the intricacies of peripheral practitioners’ backgrounds in their access to cosmopolitan media (particularly in the New York hub), the fact is that there is no deliberation about other outliers. Accordingly, Christopher Hilliard’s “Leavis, Richards, and the Duplicators” is this part’s mother lode. Nevertheless, as Lutz points out in relaying his road to professionalization, “There were national boundaries, and they mattered. There were original languages, and that mattered” (emphasis mine).

Attention to translation would have greatly enhanced this compilation, since as it stands, translated English literariness is the public paradigm for criticism of world literature. The contributors represent a diverse, youngish group, with particular devotion to south central Asia and its diaspora (greatly represented by Rabindranath Tagore). Still, factoring in Latin America—where there has been wide concern and writings about the divide in media access since the Good Neighbor Policy in the 1930s, and where the Argentine doyenne of letters read Tagore’s Gitanjali in 1914—would have greatly enriched the positionings centered on peripheral contributions to areas where print culture does not have the visibility that abounds in the first world. Since amateurism and making criticism “scientific” continue to disambiguate each other, Majumdar and Vadde duly query: “Is such interdisciplinary study the privilege of a rarefied professionalism or an ambitious form of amateurism?”

Will H. Corral

San Francisco