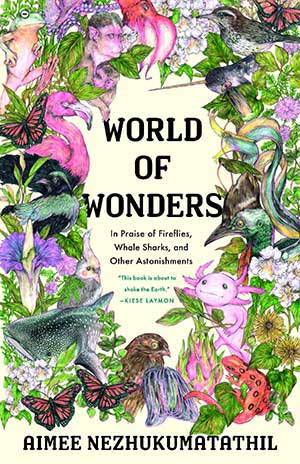

World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil

Minneapolis, Minnesota. Milkweed Editions. 2020. 184 pages.

Minneapolis, Minnesota. Milkweed Editions. 2020. 184 pages.

AIMEE NEZHUKUMATAHIL'S World of Wonders takes a poetic-encyclopedic approach to memoir. The book is as much about color and race in our modern world as it is about gratitude for the smallest and strangest miracles it still manages to hold. Each essay is structured around a particular wonder: the delicate comb jelly, the sugar-laden cara cara orange, and the corpse flower (which needs no additional adjectives), all make appearances. Each is wrapped in language that engages so deeply with its own curiosity, and with such a taste for the way certain words move in the mouth, that all we can do is share in the wonder—even taste it, if we dare follow our gasping breath into a repetition of the words that called it forth: “The bibliography of the firefly is a tender and electric dress.”

Since the beginning of the pandemic, I have had very few moments completely to myself. As I sit this afternoon, reveling in the quiet brought forth by a kite-flying adventure my partner has created for our five-year-old son, I find myself repeating out loud the same words over and over again: “The bibliography of the firefly is a tender and electric dress.” I don’t need to understand exactly what they mean to feel their ability to heal—to fill a much-needed silence with curiosity. And that’s the largest takeaway I’ve come to from this book. It is healing. It is a persistent fascination with the world that cannot be snubbed out, even in the face of unharried and well-fed racism. It is falling in love with a backdrop of blooming corpse flower, about which we learn “when the two rings of citrus-colored flowers fully bloom and the giant meat-skirt of the inflorescence unfolds, the spadix’s temperature approaches that of a healthy human body, one of the only times this happens in the plant world.”

As the daughter of a Filipina mother and Malayali Indian father, Nezhukumatathil’s experience as a brown girl growing up in America is slowly and then abruptly revealed, over and over, impressing upon the reader the ever-presence of racism and its very personal implications. Her own story of the shame put on her by a schoolteacher in Phoenix is in conversation with a later essay entitled “Questions While Searching for Birds with my Half-White Sons, Aged Six and Nine, National Audubon Bird Count Day, Oxford, MS.” Both touch on primary experiences for American children while highlighting that none of us—regardless of the color of our skin—can deny our proximity to race and its implications in our daily lives.

While most of the essays stick to the anchoring structure of a single identifiable wonder around which Nezhukumatathil’s story can unfold, it is “Questions . . .” and another entitled “Calendars Poetica,” which chronicles Nezhukumatathil’s first year as a mother, that really stirred something in me. Perhaps it’s because these particular pieces force us to reckon with what comes next, knowing as we do that the story doesn’t stop here; that each of us, into the unknowable future, deserves as much as the next to experience “the hue and cry of joy” that this world in all its color and life have to offer.

Bailey Hoffner

University of Oklahoma