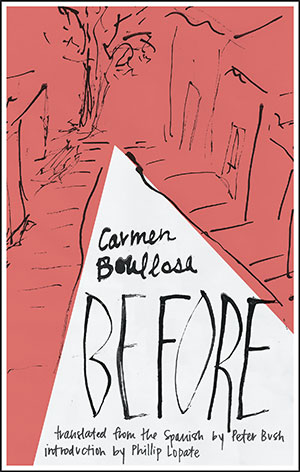

Before by Carmen Boullosa

Dallas, Texas. Deep Vellum. 2016. 104 pages.

Dallas, Texas. Deep Vellum. 2016. 104 pages.

It has taken twenty-seven years for Antes, Carmen Boullosa’s second novel, to reach an English audience. Published in 1989, the novel earned Boullosa Mexico’s prestigious Xavier Villaurrutia Award, placing her among such luminaries as Juan Rulfo, Octavio Paz, Rosario Castellanos, Carlos Fuentes, Elena Poniatowska, and Sergio Pitol; in short, a pleiad of twentieth-century Mexican writers.

Before is a small gem that brings to mind two other gems of Mexican literature: Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo and Carlos Fuentes’s Aura. This comparison is not overstated. Like its predecessors, death is a central theme in Boullosa’s novella. Before differs, however, in the playful, sometimes irreverent way in which the protagonist confronts this macabre topos. Rather than oppose life to death, as did Rulfo and Fuentes, Boullosa opposes childhood to adulthood, which can be infinitely more uncertain and frightening. In Boullosa’s binary, puberty is the dividing line. Through this paradigm, the title Before acquires new meanings.

In this first-person coming-of-age story, the narrator-protagonist attempts not so much to recount her childhood as to remember it. But our phantasmal protagonist succumbs to the shifting and unpredictable quicksand of memory. In The Art of Flight, fellow Villaurrutia laureate Sergio Pitol writes, “Memory works with the same oblique and rebellious logic of dreams, . . . rummages in dark holes and extracts visions that, unlike those of dreams, are almost always pleasant.” Pitol’s characterization seems tailor-made for our unnamed, disembodied narrator with one exception: her memories are almost always unpleasant, anxious, even terrifying. “My memories make me fearful and undermine my serenity of memory,” she tells us. Indeed, the same dis-ease of memory that plagues the narrator-protagonist pervades the entire novel and, in doing so, interrupts the story’s temporality. In short, the story does not always progress linearly; instead, it necessarily moves to and fro, in a quasi stream of consciousness that both reflects and represents the fragmentary nature of memory.

In his excellent introduction, Phillip Lopate alludes to the autobiographical aspect of the text, specifically the death of the narrator’s mother in 1954, the same year that Boullosa’s own mother died. This point, however, seems inconsequential. What’s more, in an interview with Vanessa Vilches Norat in 1999, Boullosa emphatically stated, “Mis textos no son autobiográficos” (My texts are not autobiographical).

The mother in Before does, however, play a central role, as does the spectral father Pedro Páramo in Rulfo’s eponymous novel. Just as Juan Preciado is haunted by the memory of a father he never knew, the nameless narrator-protagonist in Before is haunted by the memory of a mother she calls only Esther.

Peter Bush’s adroit translation, peppered with Briticisms, may ring a bit foreign to American readers. This foreignness, however, helps distance the text from a contemporary idiom and, in doing so, creates a temporal distance that brings us closer to the period represented in the story.

Deep Vellum has published two other works by Boullosa: Texas: The Great Theft and Heavens on Earth, an excerpt of which is featured in WLT’s all-women’s issue (Nov. 2016). Let us hope that Deep Vellum graces us with yet another Boullosa gem.

George Henson

University of Oklahoma

Get the book on Amazon or add it to your Goodreads reading list.

George Henson is a translator of contemporary Latin American narrative, a contributing editor at World Literature Today, and lecturer in Spanish at the University of Oklahoma.

George Henson is a translator of contemporary Latin American narrative, a contributing editor at World Literature Today, and lecturer in Spanish at the University of Oklahoma.