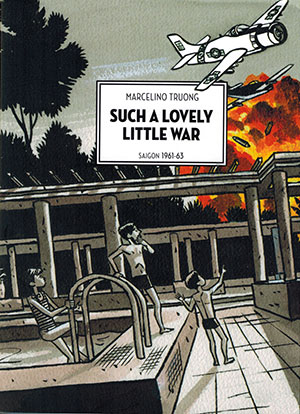

Such a Lovely Little War: Saigon 1961–63 by Marcelino Truong

Vancouver, B.C. Arsenal Pulp Press. 2016. 272 pages.

Vancouver, B.C. Arsenal Pulp Press. 2016. 272 pages.

Marcelino Truong’s newly translated graphic memoir, Such a Lovely Little War: Saigon 1961–63, the first of two volumes, is a story of events in Saigon in the early 1960s as experienced by the author’s binational family: a French mother, a Vietnamese father, and their four children. Through this occasionally bumpy translation from the French, the reader follows a family challenged by dislocation and mental illness as they move across the globe for the father’s work with the newly organized independent government of South Vietnam.

The thick-lined black ink brush artwork, sometimes washed by single watercolors, sometimes by a full palette, creates a dynamic and visceral reading experience. Next to these sensual, often frankly beautiful scenes, the detailed text-based history lessons, while understandable, attempt to clarify a distant and complicated period and can feel like a distraction. The narrative tries very hard to verbally cover and critique everything—foreign press, local politicians, colonial powers, people left in poverty—all while trying to untangle the world of a family nearly coming undone. It’s perhaps too big a job.

This tale is best when it “tells” the least—when we instead “see” young brothers channeling a violent world through fights to the death between captured cockroaches and crickets; when mapped “Ho Chi Minh Trails” are illustrated as individual men and women wading knee-deep through wetlands; or when the world is radically framed and circumscribed, reduced to the space under a dining-room table, where the author’s mother, so distraught by the war raging outside their apartment, swears in front of her kids. And when, crouched with her, fighter planes shooting outside their windows, those kids in turn find this funny: “She said ‘shit.’ Hahahaha.” When the author trusts the graphic form and allows judgment of events to emerge more subtly, the narrative is most powerful.

Less history and more sustained focus on character development within the family itself might have strengthened the story in other ways, such as in depicting the complex intersections of gender with war and family. The author’s young self’s emerging sense of women, at one point characterized by touching a maidservant’s “titties,” is offered largely as unproblematic, coming-of-age comic relief. Women and girls, though clearly lacking social or political power equal to the men, are, at times, depicted as pathologically difficult—the mother is crazy, with a still undiagnosed bipolar disorder, while the father, who works for an oppressive autocratic leader, is constructed as largely sane. The methods of the ruthless men who run the territories of North and South Vietnam are strongly critiqued as violent, but it is the wife of one of these leaders, the “Dragon Lady” Madame Nhu, who merits an entire chapter on her feminine, glamorous wickedness. Her full-frame portrait gushes, “Power is marvelous. Absolute power is absolutely marvelous.” The author’s sister—at times a sane, if one-dimensional voice—disgusted by her brothers’ violent play and the conditions of war alike, remains largely undeveloped.

This graphic memoir reminded me how much form matters. We don’t read graphic novels to make complete sense of history but rather to try to understand and process the human impact of moments in that history, through our senses, our bodies. Though words and facts were sometimes a distraction, this is a compelling story about one man’s very internal, embodied, and unfinished struggle to understand not only widespread human suffering but also a childhood that was unjustly drawn and colored by war.

Alison Mandaville

California State University, Fresno