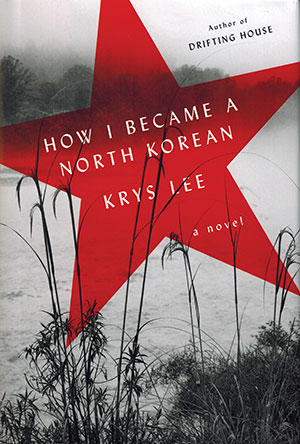

How I Became a North Korean by Krys Lee

New York. Viking. 2016. 246 pages.

New York. Viking. 2016. 246 pages.

Krys Lee’s How I Became a North Korean casts a narrative of three voices: Yongju, a North Korean exile from an affluent family; Jangmi, a trafficked North Korean in forced matrimony; and Danny, a Chinese American impaired by dogmatic faith. These lives collapse together where China borders North Korea, and each must negotiate the murder of a father, an unborn child, and the hostility of religion. In Lee’s story, there is no hero except for the possibility of what can be changed in our modern world following the failure of such characters—thus redeeming the characters’ failures as successes, all to inform the reader. What remains is the current context of being human—that is, to be willingly uninformed. To change that context, one must first engage with what it means to survive in our world.

We cannot wholly understand Lee’s characters without first considering Jeong. Jeong is a culture-specific word to Korea. It is the simultaneous bond and bondage that Western cultures define as love. But with love alone, we see Yongju, Jangmi, and Danny incompletely. Jeong is primitive, unlike love, because Jeong predates love’s romanticism. Jeong is a feral trap and release. Jeong kills and births, separates and unites—what we can “come down” or “rise up” with like a disease or cure. We have Jeong for the mother we know or do not know; we have Jeong for the country of our birth as we do for the breath in our bodies, and for these reasons, Jeong is responsible for both acts of great tenderness and violence. For Jeong, we can wage violence on behalf of something akin to tenderness. With Jeong, there is no separation between what is good or bad—only the deepest feeling that compels us to save our souls. Therefore, there is no difference between a pastor and a dictator. They are both sick with their own Jeong and soothed by it.

Using Jeong, we can enter Lee’s characters’ lives with reverence. Yongju is not a self-pitying exile, but rather he is inordinately tough—an identity composed of both self-flagellation and heroism. Jangmi is not a scrappy slave, but she is godly for aggregating worth to her life for each day she survives it. Danny’s emotions do not belong to himself, but they are a tribute to his worldliness and empathy. Yongju forgiving Jangmi can be attributed to his Jeong as much as Jangmi’s contemplating suicide from a windowsill can belong to Jeong. To read with reverence, not neglect, we can understand that these characters are a microcosm not only of the North Korean crisis but of the whole of our humanity.

As Americans, we cannot share the experience of living in North Korea. But as humans, we can feel what it is to lose willpower, to be brutalized, to condemn one’s world, country, and self. Though experiences are unique, emotions are universal. It may be common to look at traitors in terms of traitors in the book armed with gun or Bible—traitors that live in another place we do not feel responsible for. But I dare to ask this question: How much are we, as humans, traitors to ourselves? When confronted with this question, we are not confused by the word traitors. We are confused by the word ourselves.

When we begin to think of “I” as plural, though we live in a society that embraces the word “I,” we dare to see and act from a place of reverence. We call it love, but we cannot transform as shown by Lee’s characters through love alone. We must question our Jeong, the deepest parts that choose what we stand for when no one is watching, then act. The greatest inhumanity in the book is not the torture, betrayal, and slaughter. It is the silence that follows the end. It is the contemplation that this is not a story to be shelved and, at best, reviewed on paper. In another space, beyond the characters and the questions they offer, what’s left is achingly bright: inhumanity forced upon others ends the moment we know them as ourselves.

EJ Koh

Bellevue, Washington