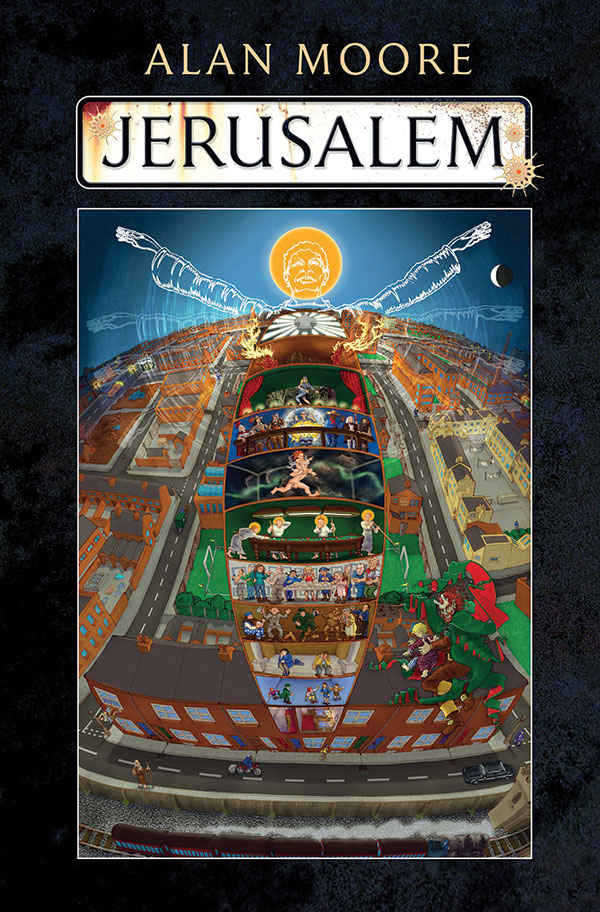

Jerusalem by Alan Moore

New York. Liveright. 2016. 1,266 pages.

New York. Liveright. 2016. 1,266 pages.

Alan Moore has constructed in Jerusalem a monolithic rendering of his hometown of Northampton, England, steeped in a timeless mythology and haunted by ghosts and devils as well as those left behind by gentrified spaces.

This sophomore novel is bookended with sections featuring Alma Warren, a painter and likely alter ego of Moore, whose name even resembles a visual and phonetic scrambling of his, as well as her muse of a brother. In the pages between the planning of a series of paintings and their unveiling, Jerusalem is split across three divisions of eleven chapters, caught in phantasmagoric drift through a millennium in the Boroughs. Its sprawling cast of characters includes sex workers, poets, cowboys, politicians, addicts, spirits, angels, demons, freed slaves, monks, and various historical and contemporary celebrities, all of whom are woven expertly by Moore into the gritty tapestry of Northampton and its shadow dimension, Mansoul. Theirs is a porous existence in which fate is as much determined by a celestial round of billiards as it is by the perceived failings of Thatcherite economics.

As with many novels of its breadth, there are moments of interaction between Moore and the attentive reader, such as an instance in which Alma reflects on the gravity of this enormous undertaking, a project she realizes she must commit to fully or risk failure. This is also a book that abounds with whimsical diversions and ontological exploration. In one extended sequence, a young boy chokes to death on a lozenge before embarking on an extradimensional journey through the cosmos. Other sections involve occasionally tedious walk-throughs of the city, pointing out landmarks or buildings as though more intent on cataloging than storytelling. Gradually, as the settings and characters begin shifting throughout the book, so too does Moore’s execution, transitioning between poetry and noir to theater and beyond. It is perhaps a testament to his range that this works very nearly through to the end.

If Jerusalem has cousins in literature, they are ambitious offerings like 2666, Gravity’s Rainbow, and most certainly Ulysses by James Joyce, whose institutionalized daughter Lucia is actually a character here, experiencing her days through a tangle of rhythmic color that almost derails the flow of an unbalanced novel that’s taken nine hundred pages to acclimate to. In reaching that milestone, however, it’s doubtful the devoted reader who has invested the time will find themselves deterred, and will perhaps even be immensely rewarded for seeing it through. Though challenging and at times lacking restraint, conquering its nearly 1,300 pages is an enjoyable experience. (Editorial note: Read Rob Vollmar’s interview with Moore.)

Michael Kazepis

Portland, Oregon