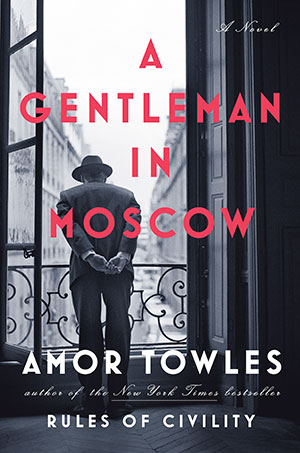

A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles

New York. Viking. 2016. 462 pages.

New York. Viking. 2016. 462 pages.

In June 1922 the charming Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov is tried in Moscow and found guilty; this verdict opens Amor Towles’s engaging new novel. Rather than being sentenced to death as an antirevolutionary, ostensibly for having written a poem deemed a call to arms, the count is made a nonperson by the Soviets and sentenced to life imprisonment in the Metropol Hotel. He will be summarily shot if he exits the premises.

Thus begins the reader’s long and enchanting acquaintance with the count over four decades, during which Rostov does not leave the hotel. But the world definitely comes to him. Somewhat akin to the Grand Hotel, the great and near great, guests, and staff populate this novel, and Count Rostov is the moving force in many of their adventures. But he is neither an observer nor a deus ex machina set apart from the action; he is very much the emotional being at the center of the novel.

Early on, he encounters Nina, a nine-year-old Metropol version of the Plaza’s Eloise. She is an odd child, wise beyond her years, who teaches the count about the hotel’s secret nooks and also brings out his paternal qualities. But Nina is only the first of his intimates during his stay, which include, among others, his old friend Mishka, a writer; Anna Urbanova, a movie star who becomes Rostov’s love interest; and, eventually, Nina’s daughter, Sofia, who is left in the count’s care. Never content to remain idle, Rostov works as a waiter and rises to be the maître d’ of the famed Boyarsky Restaurant. As such, he is the arbiter of taste, a role to which he is perfectly suited.

Other major characters are the men and women who make the hotel hum no matter what is going on outside, even the horrors of World War II or Stalin’s barbarities. In fact, news of the outside world comes only as messengers bring it or as the hotel hosts the occasional political meeting. Some readers may be disappointed that Towles does not take on the political situation in Russia during these years, but that would be a totally different novel than the one he has written. The Metropol may exist in a bubble, out of time and place, but Towles does mock those whose worlds revolve around Communist politics, like the waiter who rises through the party ranks and decides that all the labels should be removed from the bottles in the wine cellar to create a strange kind of equality. The CIA, political machinations, and notions of historical inevitability come in for a bit of skewering as well.

There is a good deal of humor here as well as some darker emotions, and many allusions to the great Russian writers, for Towles is more engaged with the Russian spirit than with the country’s quotidian concerns. The novel almost floats; we are engaged from beginning to end, and one couldn’t find a better companion than Rostov.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York City