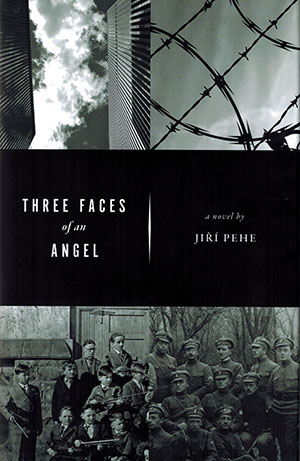

Three Faces of an Angel by Jiří Pehe

New Romney, UK. Jantar (Dufour Editions, distr.). 2014. 344 pages.

New Romney, UK. Jantar (Dufour Editions, distr.). 2014. 344 pages.

Three Faces of an Angel is a captivating three-generational Czech saga spanning the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to present day. It weaves the lives of three Brehme family members against the changing ideologies of the twentieth century in the Czech lands.

No matter whether during the elder Josef Brehme’s service in the Austro-Hungarian Army, daughter Hanna’s hiding out from the Nazis, or young Alex Brehme struggling with contemporary life, all three grapple with the Big Questions of the existence of God, fate, and suffering. Jiří Pehe, an esteemed Czech novelist and feuilletoniste, weaves the action with themes of national identity in the ever-changing central European landscape and highlights how language is tied in from one regime to the next.

Nothing wrong with showcasing a little patriotism, either. Angel is a thoroughly Czech story. Witness Josef: “I have always felt more Czech than German.” Daughter Hanna admits that “I have a dreadful urge to speak Czech.” And the westernized Alex? “I have to write in Czech.”

Josef and Hanna lead difficult lives. At key points during distress, the angel Ariel appears, providing solace and promises. Even though Alex lives a modern, “cushy life,” his center eventually does not hold and he encounters Ariel himself, thus fulfilling the book’s title.

All three generations of the Brehme family feel the need to record life’s events and feelings in order to make sense (if any) of the absurdity taking place around them. After reading his grandfather’s and mother’s accounts of atrocities, Alex feels ashamed of his own “easy” circumstances, wishing that he, too, had led “a real life.”

This novel works very well because all three disparate voices ring true. Pehe paints a realistic portrait of Josef as a Czech Legionnaire while Alex’s struggle with postmodern culture exudes sincerity. If there is one quibble, it would be that the feminine voice of Hanna could be more nuanced from the others, to make her character more plausible.

Josef’s hope that happiness can still result despite a life of suffering and unfairness will eventually resound in his daughter and grandson as well. We’re never quite sure, though, as choice and fate linger on to the last word of the story, which may be Pehe’s way of winking at his reader.

Talented veteran translator Gerald Turner turns in yet another laudatory performance here.

Virginia Parobek

Lancaster, Ohio