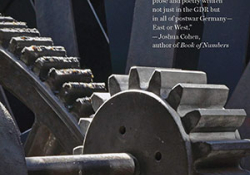

I by Wolfgang Hilbig

New York. Seagull Books. 2015. 293 pages.

New York. Seagull Books. 2015. 293 pages.

Decades after the Battle of Berlin and the fall of Nazi Germany, sociologists and laymen alike still puzzle over one of the most vexing questions to come out of the subsequent revelations of widespread atrocities: How did millions of people go along with all this? Even more troubling was the question: Could I? Wolfgang Hilbig’s novel, appropriately titled I, addresses this and many similarly knotty quandaries of the human psyche, though within the relatively milder historical epilogue known as the German Democratic Republic. Certainly the most eerie aspect of East Germany before the fall of the Berlin Wall was the elusive Stasi and their network of informants, everyday citizens coerced or intimidated or occasionally even throwing themselves at the opportunity to spy on and catalog the behavior of their fellow everyday citizens.

Cambert, the central voice in Hilbig’s novel, is just such an informant. Before immersing himself in his role as a controversial poet and acclaimed member of the literary underground, he was a self-styled poet who could barely finish a sentence, a voracious reader who never read a whole novel, a thinker forever too intoxicated for lucid thought. He worked as a grunt and lived with his mother until the Stasi came into his life, offering him the opportunity to become what he had always aspired to be, except an almost completely fabricated version.

Ironically, just the simulation of this reality is intoxicating enough for Cambert. He soon finds himself untethered from his former self, forever lost in a hallucinatory state, obsessed with fragmentary details of the life of another, more renowned writer, his mark, known simply as “The Reader.” As his jealousy of the Reader’s accolades spirals out of control, along with his unraveling sense of self, his methods become awkward and bumbled, and he has increasing trouble ingratiating himself to the very scene he was hand-picked to infiltrate.

Left without his past, and lost to his own present, Cambert’s disorienting mental landscapes bring to mind the works of Kafka, or Nabokov’s Invitation to a Beheading, but as told from the other side, from the view of one trapped and obliterated by his governmental duties, the paranoid jailer rather than the jailed, for whom “all speech had become a conspiracy.”

At first, Hilbig’s novel can seem impenetrable. The story follows no conventional sense of chronology and relies entirely on the mental meanderings of a bombastic and unreliable narrator in the middle of a profound existential crisis aggravated by a nonstop bender. Pretensions bleed into self-doubts and back again, encounters may simply be fever-dreams, and no character is consistent or capable of categorization when viewed through the heavily filtered gaze of Cambert. Through this, though, we slowly come to see one sort of psychology that is prone toward joining up with the bad guys: the listless souls, starved for meager power, sticking like burs to the boots stomping the ground around them.

Kristi Steffen

Oklahoma City