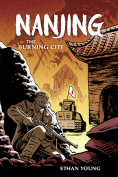

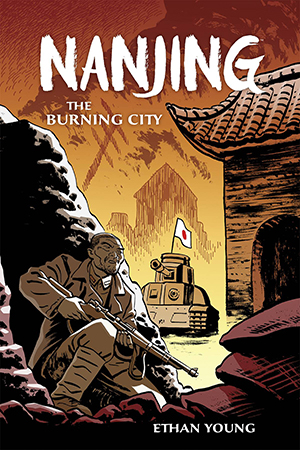

Nanjing: The Burning City by Ethan Young

Milwaukee, Oregon. Dark Horse Books. 2015. 216 pages.

Milwaukee, Oregon. Dark Horse Books. 2015. 216 pages.

Two soldiers traverse an all-but-leveled city strewn with corpses of women, men, and children as the Japanese military overrun the Chinese city of Nanjing in the early days of what would be called World War II. Estimates of the dead in this historical massacre range from forty thousand to three hundred thousand; the upper number is widely accepted. Most Americans know of the East Asian side of World War II only as a conflict between Japan and the US. Ethan Young’s graphic novel sets out to raise our awareness of this horrifically violent period of war. The son of Chinese immigrants to the United States, Young says in an essay with Paste magazine that he wanted Nanjing to be “more than a footnote.”

Young also writes that he isn’t the journalist Joe Sacco (he hates to travel). Yet Sacco’s work documenting contemporary conflict zones in books such as Palestine and Safe Area Gorazde, which offer a kind of “slow journalism” through comics form, is the comparison that immediately came to my mind when reading Nanjing. Sacco’s Footsteps in Gaza, an attempt to reconstruct a historical moment of violence from modern-day interviews and reports, comes even closer to Young’s work; both are “slow histories,” and there are comparisons to be made in their artwork, if not style, as well. Both chose to render destruction and violence in understated, detailed, black-and-white line drawings. Both use framing to support the emotional experience of the narrative: small, juxtaposed boxes create a sense of both chaos and entrapment; larger panels expand to create openness but also an extreme sense of vulnerability.

But where Sacco chooses a distinctly journalistic—if participatory—approach, Young, already at the temporal edge of possibility for interviews with adults who lived through these events, chooses to draw from history to create a fictional storyline and characters. He depicts people whose experiences illustrate what it might have been like to live through the events but, as fictions, do not lay claim to any absolute “truth” about them. In his fine narrative artwork, the story’s setting and events are most believable. The silent frames are particularly strong, giving readers a chance to encounter the narrative more viscerally. Like all fictional characters, his actors appear and speak somewhat more simply and larger than life. Yet they present a thoughtful variety of responses to their impossible situations—sometimes acting well, sometimes reprehensibly.

The protagonist, an older captain, and his companion, a younger soldier, first try to exit the city—as have their fleeing commanders. When the younger Lu is injured, they attempt to make their way to the “safe zone” for civilians set up by European powers. As they navigate a horrific terrain of recent and ongoing violence, they encounter a variety of survivors and Japanese soldiers and repeatedly have to make life-and-death choices about intervening, witnessing, or walking away from enemies and those needing help. The reader is immersed in a landscape where violence seems the only outcome, no matter whether one acts or stands aside. In a state of war, all are damaged.

A strength of this narrative is the way the gendered nature of war is explicit. A “buddy story” told from a male point of view, in which women are unseen or appear primarily as “extras,” Young nevertheless mostly avoids exploitative romanticizing. The one female character who gets significant page time is scary, even as she is also almost too idealistically courageous (and beautiful). Young also highlights the common, systematic rape of women during war. (Of course, though rarely depicted—another elision of war history—men are sometimes similarly victimized.) The reader witnesses rape only aurally, through screams of women and the talk of soldiers participating—and of those choosing not to participate. Young’s decision not to depict rape though images both avoids gratuitousness and effectively creates a story in which readers become even more complicit, as we move from positions of witness to that of narrative co-creators, imagining the atrocities for ourselves.

Young claims his point is to make this historical moment visible, and he does. The bare historical facts about what happened to this city and its people during 1937–38 are, in fact, related in a brief prose paragraph prefacing the comic. But by the end of the story, we have learned little more about these complex “facts,” about the Chinese government’s choice to sacrifice this city, whether it would have been defensible, what the Japanese did to gain the city and hold it, or how the remaining population fared. Instead, as readers, we become immersed in the impossible ethics of war—any war. This narrative succeeds less as a history lesson than as a powerful indictment of both war and its telling. That some events in war are forgotten, or deliberately erased, only serves to secure a sense that war can be a victory or encompass some kind of justice. Yet “remembering,” trying to tell or revise the history of war, risks becoming an attempt to wrest some kind of ethics or “right” view of war.

This novel begins with multiple panels that open onto an urban scene of destruction. In many of these panels, a man is bound to a telephone pole, as if for execution. It is unclear if the man is already dead or watching. The view shifts with the protagonist, yet the bound man is often in partial view: front, back, side, shadowed, or partly illuminated. In Young’s graphic novel, for all his desire to daylight events elided by those with the power to write history, there is, literally, no omniscient view, no complete description nor explanation for this war—or for its forgetting. To re-see such historical atrocities is always a fiction. And facts don’t seem to help. To learn anything from war, to move forward in a better way, we must somehow stand witness, look, and speak. After all, the corpses, the man bound to the pole, no longer can.

Alison Mandaville

California State University, Fresno