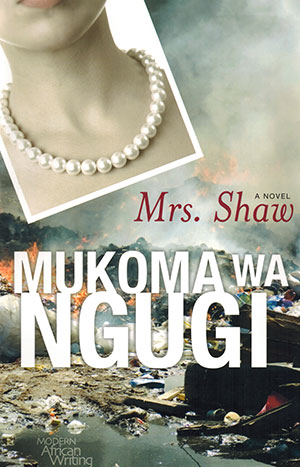

Mrs. Shaw by Mukoma Wa Ngugi

Athens, Ohio. Ohio University Press. 2015. 235 pages.

Athens, Ohio. Ohio University Press. 2015. 235 pages.

Mrs. Shaw takes place in two vastly different settings: the Kwatee Republic, a fictitious, pan-African name for Kenya, and Madison, Wisconsin. The first chapters introduce Kalumba and his close friends from the movement, Ogum and the less-privileged Sukena. Moreover, they relate the brutal repression—including the murder of Ogum’s father, a preacher—leading to Kalumba’s clandestine escape. Kalumba’s journal, the diary of an exiled activist writing his dissertation in Madison, constitutes the second section. The final chapters of the novel, whose settings make manifest its structure, relate Kalumba’s return, doctorate in hand, from his ten-year exile.

Kalumba encounters Mrs. Shaw in a Madison bar. A retired African history professor, she catches her compatriot’s attention by her repeated presence there and by telling him he needs a “white mother.” The British retiree subsequently reveals she was a murderer, that she had shot her husband, a colonial district officer, blamed his death on wild animals, and kept his bullet-ridden skull as proof. By revealing she killed a British officer, Mrs. Shaw inadvertently risks undermining the new nation’s narrative of black agency in the insurgency. Upon his return to celebrate their electoral victory, Kalumba undermines the nation’s view of the movement when he reveals, without authorization, the site of the massacre he witnessed before fleeing. In both cases, Wa Ngugi unveils the historical reality hidden behind widely held beliefs.

Kalumba also meets Melissa, exiled from her Puerto Rican homeland, in the bar the three exiles frequent to assuage their “bitterness.” Having become lovers—a process the diary documents—Melissa and Kalumba care for Mrs. Shaw, suddenly stricken with Alzheimer’s. They leave notes reminding her to eat breakfast, etc. The author brilliantly renders Mrs. Shaw’s frequent lapses by having the aging woman revert to her former colonial mentality and ask herself if she should allow the couple to sit at her table. Through Mrs. Shaw and Kalumba—the latter can’t remember if, unheroically, he “talked” during his pre-exile torture—the author reflects on the blind spots of individual memory and compares it to the new nation’s constructed view of itself.

Wa Ngugi introduces his novel with an epigraph that makes reference to Maurice Bishop, Ruth First, and Thomas Sankara and informs the reader that his novel deals with betrayal. Kalumba is welcomed home, reunited with his father, reintegrated into the rituals of his ethnic group, and acknowledged as a popular hero after revealing the site of the massacre he’d witnessed firsthand. The rally to celebrate the movement’s election, however, is orchestrated in such a way as to demonstrate the difference between Kalumba’s conception of the new republic and that of the movement’s newly sworn-in president.

Supportive of truth-affirming Kalumba, Melissa and Sukena represent a transnational feminine entente that offers hope after the fratricidal betrayal. Staggered by the magnitude of the events the day she first arrives in Africa, Melissa nonetheless intuits that “the Sukena of tomorrow would be more dangerous” than anything the “new and old” Kwatee Republic had ever experienced.

Robert H. McCormick Jr.

Franklin University Switzerland