Casting Shadows: Anke Feuchtenberger’s Comics and Graphic Narration

Pathos und Peinlichkeit.

Pathos and awkwardness.

Aus dem Land, wo die Sprechblasen Schatten werfen.

From the country where speech bubbles cast shadows.

– Anke Feuchtenberger, interview, 2009

In an interview published in European Comic Art, East German–born comics artist Anke Feuchtenberger revealed the dictums of her artistic production.[1] The first, “Pathos und Peinlichkeit,” engages the aesthetic content of her art. Dark, expressive, and innately corporeal, Feuchtenberger’s panels reveal the fundamentals of human nature: emotiveness, passion, pain, and sex. Feuchtenberger’s second aphorism, on the other hand, “aus dem Land, wo die Sprechblasen Schatten werfen,” provides insight into the context from which her art emerges. Connecting notions of national identity and national history, it situates her comics in a tradition of specifically German comic art. She also draws connections to more recent German history, referencing both the country in which she currently works, united Germany, and the socialist state in which she was trained, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), where the comics medium was dismissed as capitalist propaganda. Trained under the doctrines of socialist realism, engaged in traditional printmaking techniques less favored by West German art academies, and working without an established comics canon, Feuchtenberger pushed German comics into a new realm, redefining the medium in cultural, political, and aesthetic terms.

Born in an East Berlin house in 1963 to a graphic designer father and an art teacher mother, Feuchtenberger was heavily influenced by the art she encountered as a child. She began studying the fine arts at the age of fifteen in evening classes at the Berlin Academy of the Arts. After four years, she accepted a two-year photography internship, and in 1983 she entered the graphic design program at the Academy for Visual Arts, Berlin-Weißensee. There she and other students (Henning Wagenbreth, Detlef Beck, and Holger Fickelscherer) formed the oppositional group PGH Glühende Zukunft.[2] Looking to the American underground comix scene as a model, Feuchtenberger and the group fostered a new avant-garde comics movement in Germany that broadened the aesthetics of the medium, changed public opinion about the legitimacy of comics, and developed an independent comics scene that continues to be influential today.

The first phase of Feuchtenberger’s professional artistic production is her most overtly political. Spanning from her graduation in 1988 until after German unification in 1991, it is characterized by the artist’s work with the Independent Women’s Association and her activism in the East German Women’s Movement. After the opening of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, the women of East Germany rallied to influence the course of the revolution. While popular sentiment called for the unification of Germany, many intellectuals and activists sought governmental reform rather than complete abolition of the state. These activists did not see the Federal Republic as the “better Germany” and criticized West Germany’s excessive consumerism. They also recognized, however, that the GDR was in need of fundamental change. Committed to developing democracy, these East German activists also shared a dedication to socialism that had developed over the forty years of the GDR and sought to maintain its achievements.[3] Consequently, a movement committed to a “third way” aimed to reform the GDR to re-create the nation as an autonomous, democratic state rather than dismantling it as history actually unfolded. [4]

Feuchtenberger worked in collaboration with the activists of the Independent Women’s Association to produce posters advocating for the rights of women and children and encouraging citizens to vote in East Germany’s first democratic elections in 1990. Her work during this period is optimistic in its expression of utopian ideas about the future of women and women’s rights. Featuring strong central and often naked female figures, Feuchtenberger’s early posters express the political movement’s excitement about the role of women in determining the future of Germany. By the election in March 1990, however, the illusion of political reform was shattered by a vote in favor of unification.[5] Instead of East German reform, or even an amendment of the West German constitution, the German Democratic Republic was simply dissolved and its lands adopted as the five new states of the unchanged political system of the Federal Republic, rendering all efforts by the Independent Women’s Movement moot.[6] Consequently, Feuchtenberger’s art became more pessimistic, the line work bolder and colors darker. And while her earlier projects engaged in public debates on the future of Germany, after 1993—disillusioned with the democratic process—Feuchtenberger’s art turned inward to investigate similar criticisms of the established patriarchy. Similarly, her work moved away from the unitary single image she had employed in her political artwork and in a body of theater posters to embrace comics and graphic narrative.

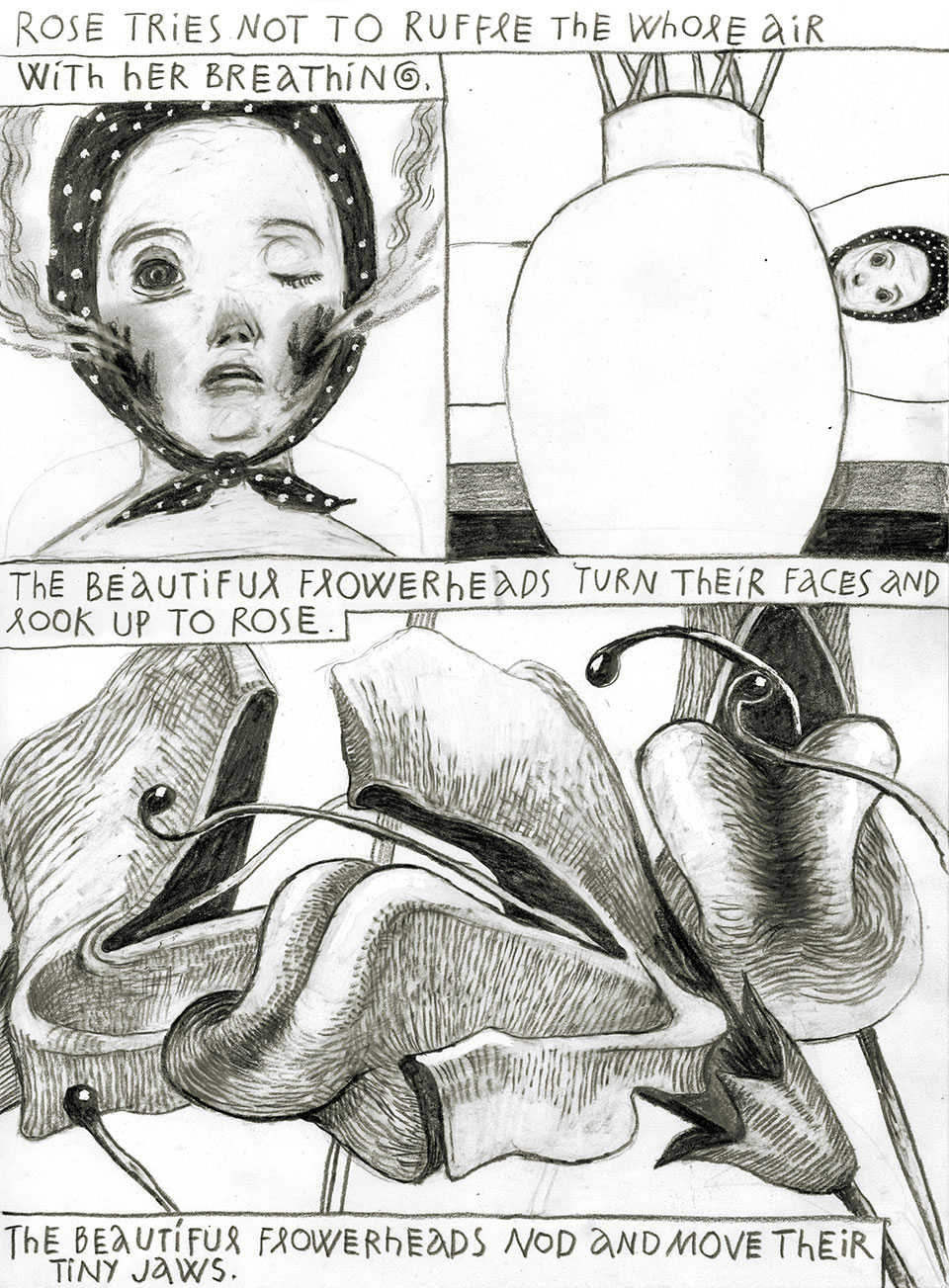

Feuchtenberger’s graphic narrative is unique in the comics canon, resembling graphic poetry more than conventional comics.

Feuchtenberger’s first official publication, Mutterkuchen (Jochen Enterprises, 1995), is a collection of nine stories. “Mutterkuchen,” the German word for placenta, is an appropriate title for her introductory work. Not only are the themes of motherhood and birth most prominent (her only child, Leo, was born before the fall of the Berlin Wall), but as a collection of Feuchtenberger’s comics from between 1989 and the time of its publication, it could also be considered the afterbirth of her first mature artistic endeavors in the comics medium. Mutterkuchen is Feuchtenberger’s most aggressive, candid, and unpolished work as well as her most feminist, maintaining a concern with the female body and matters of gender relations throughout its stories.

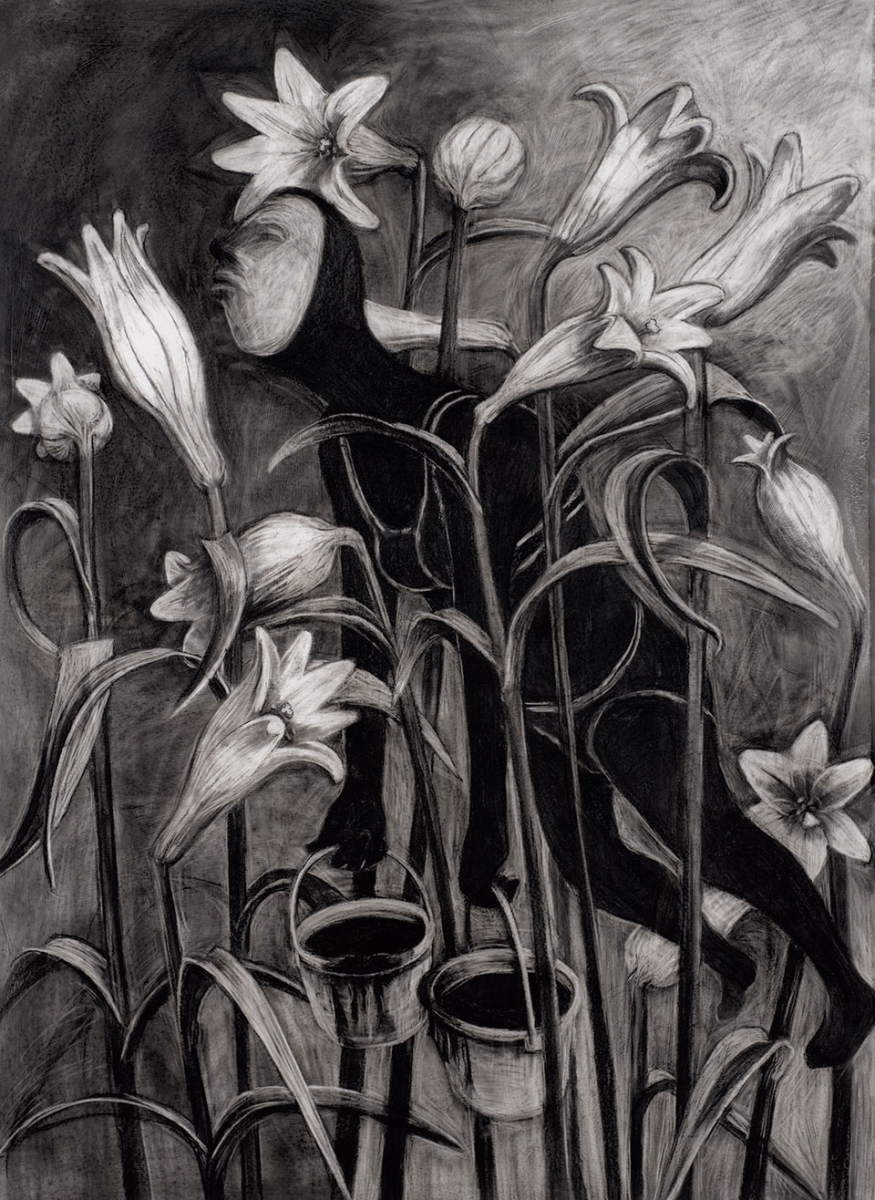

Feuchtenberger’s graphic narrative is unique in the comics canon, resembling graphic poetry more than conventional comics. Experimental in style and content, Feuchtenberger draws on numerous influences in her work. Her visual language is reminiscent of German expressionism, but she has incorporated a feminist perspective in representing the visceral nature of sex and human experience. Her early work emulates the style of woodblock prints, German expressionist poster art, and the aesthetics of expressionist film stills. Her later work, however, is replete with the rounded figuration, predisposition to charcoal, and preoccupation with the female body characteristic of Käthe Kollwitz’s (1867–1945) graphic art.

Feuchtenberger’s entire oeuvre is innately personal, detailing accounts of motherhood, sexual experience, relationships, and inequalities between men and women. While she vocally resists the category of autobiography, her stories retain important connections to her biography and thereby offer a coded and metaphorical exploration of the author’s life. But through simplicity of form, symbolism, and an aphoristic style of communication, she abstracts her personal experience to imbue her graphic narratives with mythological qualities that foster a sense of universality. She strips bodies of their material possessions and real-world contexts until her characters literally run naked across surreal landscapes and all objects emerge as metaphors potent with meaning. More specifically, her stories resonate with reflections on gender relations in contemporary Germany. So even though the content of her art remains intimate and personal, the political and feminist discourses it engages are distinctly public.

Feuchtenberger strips bodies of their material possessions and real-world contexts until her characters literally run naked across surreal landscapes and all objects emerge as metaphors potent with meaning.

The series Die Hure H (1996; Eng. W. the Whore, 2001) is Feuchtenberger’s most well-known project and connects the second and third phases of her artistic production. Deeply metaphorical and steeped in symbolism, the Hure H series of graphic novels is dark, pessimistic, and packed with allusive meaning and ambivalent messages. A collaborative project with poet Katrin de Vries that spans over a decade, Die Hure H (1996), Die Hure H zieht ihre Bahnen (2003; Eng. W. the Whore Makes Her Tracks, 2006), and Die Hure H wirft den Handschuh (2007; W. the whore throws the glove) present short graphic narratives on the plights of womanhood. The project, which features the Hure H as its protagonist, seeks to uncover the cultural nexus hidden behind the cliché of the whore figure through the abstracted representation of female experience.[7] The Hure H thereby stands in for all women in her existential search to rid herself of masculine oppression.

The comics progress chronologically, and as the Hure H ages, the reader witnesses her becoming more realistically represented with every story. Each narrative presents a problem for which the protagonist seeks a solution. However, these problems—the desire of men, the aspiration toward beauty, the search for a husband, and marriage in a white dress—are all presented as societal expectations that the Hure H learns to disregard by the end of the final panel. She embraces another woman instead of learning to desire men; her search for a husband leads her to a land of dead men, and only then is she set free; and she removes the white dress that freezes her body to find warmth in her nudity. Society’s oppression is represented through layers of clothing; ironically, the Hure H is only freed from the pejorative nature of her whore status when she unbinds her figure, lets down her hair, or removes her dress. Embracing her body, angular and ugly or fleshy and round, is therefore the only path to the Hure H’s freedom.

Feuchtenberger’s most recent phase of artistic production illustrates yet another dramatic shift in her art. Moving away from the expressionist woodblock print aesthetic of her earlier art, Feuchtenberger’s work since the early 2000s is softer, rounder, and more commonly in charcoal. The scale of her art has also considerably changed, with many of her pieces now produced in an oversized format. Feuchtenberger’s work during this period exhibits even more experimental forms of graphic narration, both in terms of formal characteristics as well as narrative technique. In Das Haus (The house) from 2001, for example, Feuchtenberger divides the human body into thirty parts, each occupying the uppermost level of thirty towers. The lower five or six floors then each exhibit an image that Feuchtenberger aims to link to the chosen body part as well as a portion of a sentence, constructing a sort of narrative as the reader moves through the levels of the house. Yet these visual and textual chains of association resist comprehension, and the process of connection itself is highlighted as the author’s intention, rendering her art poetic in the linking of disparate objects through graphic narration.[8] In 2008 she published a second experiment in visual poetry, wehwehwehsuperträne.de (www.supertraene.de). The images gathered function as both a collection of independent works as well as a graphic narrative, where the reader is essential in linking the images together to create the story, thereby producing a unique engagement with every rereading of the collection.[9]

While this illustrates how much of her art has remained poetic in visual style and narrative strategies, her recent comics have also begun to embrace more traditional techniques from the comics medium. Feuchtenberger’s 2012 publication, Die Spaziergängerin (The woman taking a walk), a collection of comics projects originally published in a variety of media, features stories of travel and her native Berlin and exhibits a variety of graphic narrative techniques to provide an overview of the breadth of her artistic production. Moreover, unlike her earlier work, which remained abstract in its investigations into Feuchtenberger’s biography, the artist has also begun to overtly examine her youth and upbringing in the German Democratic Republic.[10] In tune with the current movement in German-speaking graphic novels thematizing East German experience, Feuchtenberger’s comics about her childhood engage the intersection of history and memory that is so important to the last generation of East German citizens still negotiating the representation of their past today.

Equally important to Feuchtenberger’s contribution to reinventing the medium are the more recent roles she has adopted to cultivate the contemporary German comics scene. Since 1997, Feuchtenberger has worked as professor of drawing and media illustration at Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, where she has been training the next generation of German comics artists. Aisha Franz, Sascha Hommer, and Marijpol as well as such internationally acclaimed and translated authors as Birgit Weyhe, Arne Bellstorf, and Line Hoven have all participated in Feuchtenberger’s courses on drawing and graphic narration before moving on to successful careers in German comics. There, she helped her students found Orang Magazin, which published student content between 2002 and 2012, featuring many of Germany’s most important graphic novelists today. Lastly, in 2007 Feuchtenberger and her partner Stefano Ricci founded MamiVerlag, an independent publishing company that aims to introduce young and unknown comics artists to the international comics scene.

As an artist, Feuchtenberger has redefined the potential of the comics form for her German-speaking audience through an engagement with diverse sources and new techniques in graphic narration, elevating the medium to an art form after 1989. By virtue of her teaching and publishing efforts, Feuchtenberger has also left an equally significant mark on the contemporary comics scene, perceptible in her students’ successes as well as in their inclination toward intense metaphor, surrealism, and fantasy in their graphic narratives. It is the combination of all these roles, however, that makes Feuchtenberger such an important figure in German art today. As a professor and publisher, Feuchtenberger imparts her knowledge and experience to the next generation of comics artists, but as an artist, she continues to innovate graphic narrative, thereby influencing, inspiring, and shaping the German comics scene from above as well as within.

University of Michigan

[1] Mark David Nevins, “‘From the Land Where the Word Balloons Throw Shadows’: An Interview with Anke Feuchtenberger,” European Comic Art 2, no. 1 (2009): 75.

[2] Nevins, “From the Land,” 67.

[3] Lynn Kamenitsa, “The Process of Political Marginalization: East German Social Movements after the Wall,” Comparative Politics (1998): 322.

[4] Gottschalk, “Extrem laut und unglaublich vergessen,” Missy Magazine, February 21, 2014; Kamenitsa, “The Process of Political Marginalization,” 322.

[5] Brigitte Young, Triumph of the Fatherland: German Unification and the Marginalization of Women (University of Michigan Press, 1999), 5.

[6] Myra Marx Ferree & Brigitte Young, “Three Steps Back for Women: German Unification, Gender, and University ‘Reform,’” Political Science and Politics 26, no. 2 (1993): 199.

[7] Anke Feuchtenberger & Katrin de Vries, back cover, Die Hure H zieht ihre Bahnen (Reprodukt, 2003).

[8] Zygmunt Januszewski, “Zeichnung als Vorsprache / Anke Feuchtenberger im Gespräch mit Zygmunt” (2011), vimeo.com/33182914.

[9] Matthias Schneider, “Surreal Worlds of Pictures and Secretive Stories – Anke Feuchtenberger,” Goethe Institut, Dec. 2012.

[10] Feuchtenberger, “Ein deutsches Tier im deutschen Wald” (2013), “Lob des Kohlenstoffs – Zeichnungen und Bildergeschichten von Anke Feuchtenberger,” Internationalen Comic-Salons Erlangen, Kunstmuseum Erlangen, June 15–20, 2014; Feuchtenberger, “Effi redet Blech,” Orang X – Heavy Metal (Reprodukt, 2013); Feuchtenberger, “Neuigkeiten aus der Alten Schule,” Die Spaziergängerin (Reprodukt, 2012).