Frémok: Comics Out-of-Bounds

Even in the diverse world of Franco-Belgian independent comics, there is no publisher quite like Frémok. The name itself is a neologism—a combination of Fréon and Amok, the two publishers that merged to form the new entity. A hybrid itself, Frémok constantly reapproaches, readdresses, and reinvents the comics medium by repeatedly hybridizing fine arts and narration at the extreme limits, wilfully disregarding the conventions of the comics form. Despite the diverse artistic media used to produce Frémok comics—woodcuts, oil paint, graphite, carbon paper, lithography, and more—Frémok insists that the book is itself an artistic production, and they give extraordinary care and attention to bookmaking. Beyond publishing, Frémok functions as a “platform” for new projects that expand the organization’s fundamental thesis across a spectrum of activity that includes exhibitions, site-specific installations, and, increasingly, collaborations with other institutions.

The beginnings of what would later become Frémok took place in a distressing period for francophone comics. The profound renewal that came with the countercultural explosion of the 1960s and ’70s seemed to be definitively over two decades later. By the second half of the 1980s, francophone comics, or bande dessinée, had become as standardized in their own way as the DC/Marvel-style superhero comic books in the US. Overwhelmingly, publishers adhered to the oversized, forty-eight-page hardcover “album” format (perhaps best known to American readers as the standard format for Tintin and Asterix volumes). Publishers produced countless series with endlessly recurring characters in established fictional genres, privileging the eternal return of conventional artistic styles.

A hybrid itself, Frémok constantly reapproaches, readdresses, and reinvents the comics medium by repeatedly hybridizing fine arts and narration at the extreme limits, wilfully disregarding the conventions of the comics form.

Yet the change was already there in essence, notably at Saint-Luc Bruxelles, famous for being the first European art school to have a curriculum especially devoted to comics. The students at this school would form the core of the future publisher: Éric Lambé, Dominique Goblet, Jean-Christophe Long, the twin brothers Denis and Olivier Deprez, and Thierry Van Hasselt. All of them still emphasize today the major influence of Michel Céder, lecturer in semiotics and art history. He claimed that comics were still largely underexploited and would gain much if they could develop beyond their entertainment status and enter into a dialogue with other art forms. Publishing comics along with photographs, poetry, or illustration, the Spanish magazine Madriz was regarded as a template. In 1990 most of the cartoonists from Madriz took part in an exhibition devoted to contemporary comics at Madrid’s Museo Reina Sofía. Among the foreign participants, the students and young graduates from Saint-Luc chose to christen themselves “Frigo.” Significantly, the very first public act of the collective was not a publication but an exhibition; many more would follow. On this occasion, Céder wrote a text that now sounds a bit like a manifesto: “History has taught us that art has to be the deconstruction of a norm. . . . It is necessary to say and say again that formal work is not to be confused with formalism . . . the meaning is built by the form. . . . In each work, we have to replay the idea of comics: because to break up the norms is to place oneself at the boundaries of one’s art form.”

The birth of Frigo in 1990—renamed Fréon four years later—was part of a larger international phenomenon. The total inaccessibility of mainstream publishing houses to new, unique voices meant that it was no longer necessary to compromise; the comics field had become again a virgin land where everything would be possible. To allow their aspirations to become reality, young authors did not have any other option than to join forces and begin publishing themselves. Besides the Fréon group and others in Belgium (Pelure Amère, Bill, La Cinquième Couche), similar alternative structures emerged during the same period in Spain (Medios Revueltos), France (Amok, L’Association, Cornélius, Ego Comme X), Italy (Mano), Switzerland (Strapazin, Drozophile, Atrabile), and Germany (Boxer, Reprodukt). Notably influenced by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s anthology Raw, they all considered comics to be the expression of a singular voice, as far as possible from the idea of commercial product. Jean-Christophe Menu, the cartoonist and co-founder of the French publishing house L’Association, emphasized: “It’s worth noting that, if some of the national mainstream styles may export poorly to other countries, . . . their independent alternatives stem from a truly international culture.”

All the independent publishers from different nations found common cause with one another, but Fréon in particular was closest to the Paris-based French publishing house Amok. By 1994, both publishers produced, as their primary projects, periodical comics anthology magazines: Fréon published the anthology Frigobox, and Amok published Le Cheval sans Tête. The two magazines shared not only overlapping aesthetic tendencies that pushed the boundaries of comics but even the contributions of specific artists who produced work for both magazines. But if Fréon came from the need to collectivize a group of authors who decided to publish themselves, Amok for its part was not, strictly speaking, a collective but rather grew out of Olivier Marboeuf and Yvan Alagbé’s will to create a structure to express their editorial point of view about comics. According to Alagbé, “We wanted to create a publishing house in order to work with other people—we never defined ourselves as self-publishers. Our goal was not to show only our own works. We turned naturally toward comics because there were many things to do in that field.”

In order to bolster this international publishing community, in 1995 Fréon and Amok organized Autarcic Comix, a series of events that brought together independent publishers including L’Association, Ego Comme X, and La Cinquième Couche for exhibits, discussions, and pop-up points of sale directly to readers. The retail component was not insignificant: at the time, even specialized bookshops were reluctant to sell alternative comics, so this DIY effort represented a way to get around dominant distribution channels.

Over several years, this traveling event fostered a still closer collaboration between the two publishers, who by 1999 had each shifted focus from publishing anthology magazines to the more challenging task of publishing books by individual artists. A rapprochement between Fréon and Amok seemed quite natural given how close they were in terms of editorial ethics and aesthetic choices. In 2002 the two merged to form Frémok. At a formal event including discussions, an exhibit, book signings, a “Frémokian barbecue,” and dancing, the parties involved signed a treaty in keeping with a legal text from the origins of the European Community—a manifestation of their taste for détournement and for staging oneself that recalls Dada, the Situationist International, and the Collège de ’Pataphysique. A press announcement about the union playfully noted that “The signing by Éditions Amok and Fréon of the Treaty of Frémok (FRMK) on June 22, 2002, gave birth to a giant of graphic literature that already possesses a nearly 85 percent market share of the comics of pure creation (BDCP) according to the latest available statistics.”

Frémok comics are still today often described as difficult works that require an effort from the reader. Yet according to Yvan Alagbé and Thierry Van Hasselt, the contemplative comics of Vincent Fortemps—with their complete lack of plot and characters with very imprecise identity—are a lot easier to read than extremely popular creations like Edgar P. Jacobs’s Blake et Mortimer. While the imagery and narration of books like these may sometimes be mysterious, their approach to form remains fully open, and the mise en page (or panel layout) is often quite straightforward in comparison to the complicated codes and conventions of the typical comics page, which relies on cultural initiation and familiarity to decipher. It is true that many of Frémok’s books may seem utterly baffling when we consider them only from the “good story” perspective. But if comics are often called “graphic novels,” it could also be meaningful to regard some of them as “graphic poetry.”

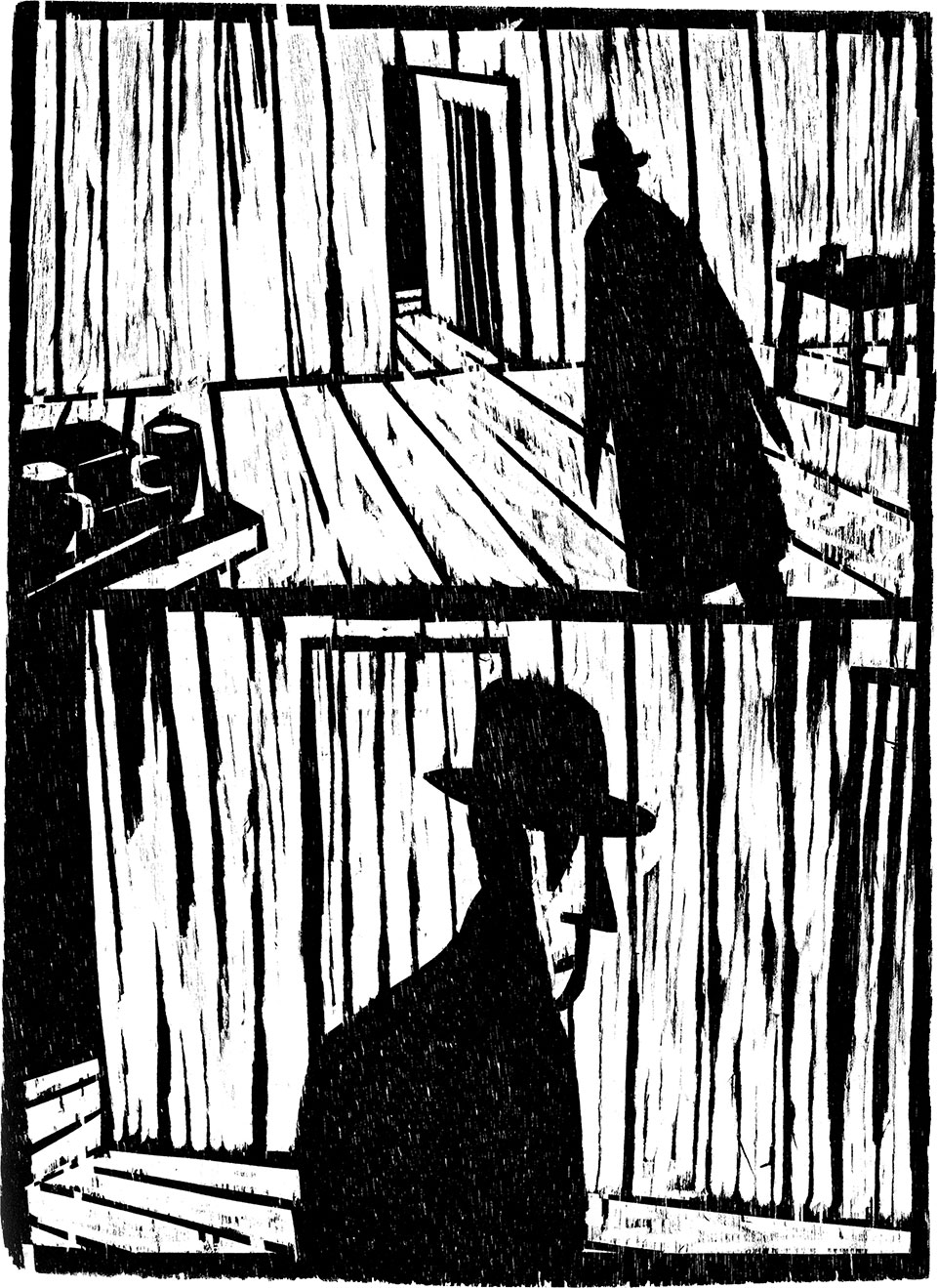

Many Frémok books express the idea that the emotional appeal of art should not be sacrificed for the comprehensibility of the plot. In Olivier Deprez’s free adaptation of Franz Kafka’s novel The Castle, the use of expressionistic woodcuts emphasizes the rawness of the human relations. The glut of black areas translates metaphorically the sensation of being smothered by a merciless bureaucracy. Gloria Lopez, by Thierry Van Hasselt, shows numerous gray values where the pictorial substance is quite literally dripping or bursting like soap bubbles. Panels are made from monotypes mixing black ink with paint thinner. Such drawings expressing uncertainty are congruent with the fragmented narrative and the depiction of a prostitution underworld. Cîmes (Peaks), by Vincent Fortemps, is drawn with charcoal on both sides of transparent plastic sheets, sometimes slashed with a knife. This allows Fortemps to create lighting effects that emphasize the evanescent nature of his wordless comics. These images evoke a waning rural world that seems to disappear like childhood memories.

Frémok authors have supported from the very beginning the idea that their creations have the same meaning and effect when put in an exhibition space as they do in the pages of a book.

The German expressionist group Die Brücke and the Vienna Secession painters are some of the references that come to mind when looking at these works, rather than typical line art–based comics. The free use of such pictorial techniques established the publisher’s aesthetic identity and has allowed Frémok to travel more freely between the contexts for comics and fine art. In general, most original comics pages shown in a 3D space appear to be a modest testimony to a work whose overall aim is to be printed; original comics art often appears to be a step in a process rather than an intentional aesthetic object. Frémok authors, however, have supported from the very beginning the idea that their creations have the same meaning and effect when put in an exhibition space as they do in the pages of a book. To quote Christian Rosset, they distinguish themselves through their capability to “hold the wall.” The multidisciplinary artists of Frémok are heavily involved in a major trend in contemporary alternative comics, what Jean-Christophe Menu has described as “the progressive erosion of boundaries.” Today Frémok defines itself more as a “platform” for projects rather than a publisher. Yet the link with comics is never totally absent. Thierry Van Hasselt states, “We always like to be a little somewhere else and stay in comics at the same time.”

Furthermore, if the idea of making visual poetry or prioritizing pictorial matter characterizes the Frémok aesthetic, their diverse body of more than one hundred published books cannot be reduced to these concepts. Three years ago, Frémok surprised the little world of comics by publishing the cartoony Cowboy Henk, by Herr Seele and Kamagurka. The Flemish duo has produced a body of short pieces starring the titular, buffoonish character since the 1980s, featuring regressive humor mixing nonsense, sexual confusion, and Belgian mythology in a “classical” drawing style evoking midcentury humor comics for children. As Frémok’s catalog becomes richer, nuances arise to reveal an always more complex editorial personality. “What we are interested in is to publish authors who bring you to an unlikely area of comics,” explains Thierry Van Hasselt, “where you never thought you could go. Few foreign or ‘out-of-bounds’ areas. When you compare two books, they may have great discrepancies. Although I have the feeling that when you put all the pins on the map, you see directly how they are linked up.”

The will to “erode boundaries” and be “brought to unlikely areas” is eloquently illustrated by the publisher’s new imprint, Knock Out. This “platform of experiments” is born out of the meeting between Frémok and La “S” Grand Atelier, an art center with several studios for creators with mental disabilities located in the municipality of Vielsalm in the rural south of Belgium. This collaboration began in 2007 with a comics workshop in which artists associated with Frémok produced comics collaboratively with artists working at La “S”; that first meeting resulted in the published anthology Match de catch à Vielsalm (Wrestling contest in Vielsalm). Several other projects—including books, exhibitions, lectures, theoretical papers, and artists’ residencies—have followed, celebrating “the wealth of hybrid projects.” A body of more recent multimedia collaborations was documented in the anthology Knock Outsider! alongside texts discussing the ethics and aesthetics of outsider art and the overall project. The Knock Out imprint was established to signal Frémok’s commitment to this ongoing and highly specific collaboration between two groups of artists.

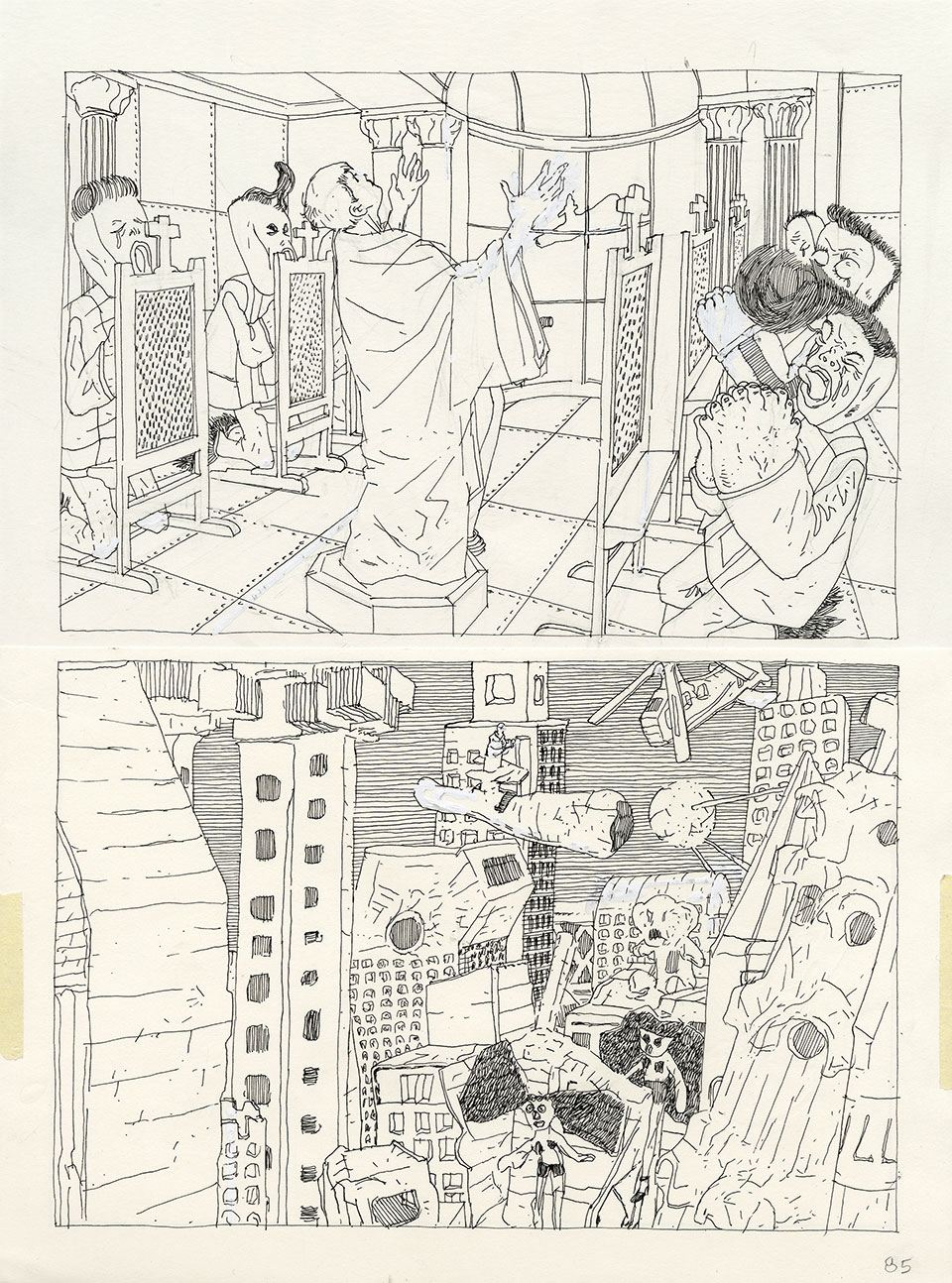

One of the most intriguing achievements currently run by this artistic joint venture was initiated by Marcel Schmitz, an artist with Down syndrome. Since 2011, he has embarked on a mammoth 3D utopian city made with cardboard and scotch tape: FranDisco. According to its founder, the place is famous for its Belgian endives grown under glasshouses by naked workers and for its cathedral that features a swimming pool. This permanent work in progress has given Thierry Van Hasselt the idea for a comic that would take place in this invented, constantly evolving environment. The building of the town and the making of the comic continuously enrich each other, in particular during artists’ residencies in various locations (the last one took place in the stunning Fondation Vasarely in Aix-en-Provence). These places have copiously inspired the model city’s transformations, which, in their turn, have fueled the content of the comic. In Vivre à FranDisco (Living in FranDisco), Marcel Schmitz intervenes from time to time in Van Hasselt’s comics panels. This organically built work tells not only a story that takes place in its imaginary metropolis but integrates the process of its own creation into its fictional content.

Pages from this project and more work by Frémok artists will soon be visible to North American readers in Frémérika, a collective English-language anthology that will be published within the next year. The goal of this book is definitively not to retrospectively present the quintessence of what Frémok has already produced during its past twenty-five years of existence. Instead, most of the content planned for this volume has never been published in any language, giving English-speaking readers the opportunity to witness an editorial project that continually redefines its forms and its uses. The plans for this publication follow an increasing presence by Frémok at American comics festivals including the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival; SPX: The Small Press Expo in Bethesda, Maryland; and the MoCCA Arts Festival in New York City. Additionally, Parecer es mentir (Pretending is lying), by Dominique Goblet—one of the core Frémok authors since Frigo’s earliest days—is forthcoming in translation from New York Review Comics, the new comics imprint established by the New York Review of Books. These steps all represent a literal transcontinental boundary-crossing by this unique publisher, so that North American readers—and artists—can more fully experience and consider Frémok’s boundary-breaking form and content.

Liège, Belgium