International Comics: Five Groundbreaking Publishers

nos:books

Taipei, Taiwan

I first encountered nos:books at the 2014 edition of the New York Art Book Fair, the massive, crowded event for which artists’ book institution Printed Matter annually transforms MoMA’s PS1 space in Queens into an international emporium of art books, artists’ books, prints, zines, and other material from the world of fine art and visual culture. The NYABF is always a dizzying cultural discovery zone, but for me specifically it presents an annual opportunity to check in and see how, and to what extent, comics are represented at an event more closely aligned with the world of contemporary art than the typical literary book fair or comic-book festival.

Comics-connected publishers and artists including Edie Fake, Drawn & Quarterly, World War 3 Illustrated, Colour Code, Lagon, and others have appeared there over the years. The most significant crossover artist of 2014 was Aidan Koch, whose beautiful pencil-and-gouache graphic novel Impressions debuted at the NYABF from art-book publisher Peradam. But these are all known quantities to me, and my observations feel almost anthropological as I warmly survey the slowly growing acceptance of comics within the world of contemporary art.

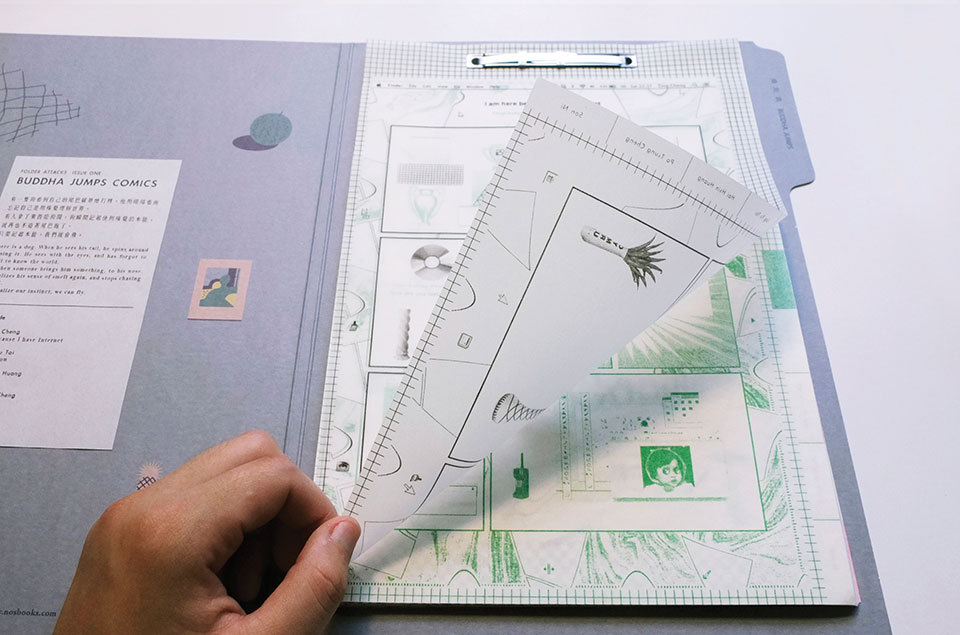

But at the tail end of my visit to the 2014 fair, I paused at a spare table of small, minimalistically designed books, and a unique object caught my eye: a gray file folder decorated with geometric images. My eye wandered over the four pieces of text on the cover: Folder Attacks / Issue One / Buddha Jumps / Comics. “Comics” nailed my eye to the book (this has happened before), and I reached out and opened it. Folder Attacks: Issue One, subtitled Buddha Jumps, is unlike any comics anthology I’d ever seen before. The book functions precisely like a file folder, with a metal clip fastener across the top, binding into the folder pages that must be flipped upward to be read in succession. If the clip-and-flip binding proceeds functionally from the file-folder format, its possibilities push deeper into groundbreaking aesthetic territory. The pages alternate between transparent and opaque, with graphic elements on each layer that first function in concert, then separately as the pages turn. More than a year later I continue to be intrigued by this unique and rare object.

The two principals behind nos:books are Taiwanese artist Son Ni and Hong Kong–based artist Chihoi. Chihoi is better known to the international comics community. As both an artist and an advocate for Hong Kong comics culture, he has frequently traveled internationally to comics festivals, and his work has appeared in comics anthologies across Europe. His books have been published in multiple languages, including two English-language editions published by Canada’s Conundrum Press. Son Ni, on the other hand, is an artist whose drawings fall between categories; she operates so far outside the realm of traditional publishing that she remains free to question its most basic assumptions. She tells me of the 2008 founding of nos:books:

In 2008 when I was compiling my own works, I wanted to publish my first book called I Am a Real Boy. But at that time I didn’t know what it meant to publish a book, for those works were private to me and there’s no one else I wanted to show them to. So I didn’t really publish it because I couldn’t figure out why I had to. Later I worked on my second book, Mermaid. This time I directly went to publish it without bothering to think about why. And that’s it.

Other artists of Ni’s acquaintance faced similar questions, and she came to understand the role a publisher could play in encouraging other artists as well as the pragmatism of publishing others’ work: “When distributing my own books to small shops, I thought of publishing more books so I can deal with the distribution more easily. It took just as much time to distribute one book as to distribute many books. So I began to publish the artists I like and let people know about them.”

The artists published by nos:books are from Taiwan and Hong Kong, though many of them now live abroad in Europe or the US. Ni’s own work, like her recent collection of drawings The Calabash, skirts the line between drawings and comics. The overall output of nos:books, now numbering eighteen titles, displays a similar range. Other than Chihoi, few of the nos:books artists identify as comics artists per se, though many have produced comics (if only at Ni’s instigation). “I don’t have a very clear picture of what’s going on in Taiwan’s comics scene and its market,” Ni admitted. “But like many of my generation, I grew up reading most Japanese manga, and now I still read them. But those artists who participate in Buddha Jumps do not usually draw comics. Some of them never read comics, and some of them don’t even know how to read the sequence in comics. I found it very interesting to interpret comics from their point of view.”

I asked her about the transparency concept that drives the book. “For me, the process of drawing comics goes through two different ‘layers,’” she explained. “The first is the plot, the storyline. And the second would be how to make the set, or to create the atmosphere, or the surroundings of the characters, to build the props, etc. And so when I started Buddha Jumps, I set the criteria, or constraint, to use transparency and see how the artists would create their narration with it. As they normally don’t draw comics in their usual practice, they bring new ideas to the comics form.” Buddha Jumps, like many other nos:books publications, was printed in-house on Ni’s risograph printers. She explained that the transparency caused difficulties and that the first print run had to be shredded before achieving a satisfactory result.

Recent nos:books publications include Chihoi’s Pink Freud, a collection of erotic drawings based on adult films that is bound on three sides and must be cut open with a knife to be read. Another recent book is Topology in Bed by Ni’s father, Chi Tsai Ni. “He’s a normal office man,” Ni says. “When I was little, he used to make these sculptures in bed, folding the blankets into different weird shapes. This year I wanted to make a record of these works from his younger days, so I asked him to redo them for a photo session. During the shoot, he told me that his bed sculptures were inspired by the ‘blanket mountains’ when he had mistakenly stayed in love motels while traveling with friends when he was young. And so he made his bed sculptures as signals, to seduce my mom. Aha!”

Upcoming books include a book of drawings, a photography book, and a book of paintings. And of course Folder Attacks: Issue Two is in the works. Ni was not forthcoming about the format, except to say that “I hope to extend the first volume’s idea and to try different things. I hope we can finish in time!”

La Editorial Común

La Editorial Común

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Of all the South American countries, Argentina may have the deepest comics tradition, and one that is barely known in the United States. Legendary Argentine cartoonist Alberto Breccia (1919–93) is considered a master on par with Hugo Pratt, Mœbius, and Hergé in Europe, but his works are not available in the US. Héctor Germán Oesterheld and Francisco Solano López’s 1950s classic The Eternaut (El Eternauta) has only recently been published in a North American edition by Fantagraphics. Quino’s comic strip Mafalda of the 1960s and ’70s has earned comparisons to Charles Schulz’s Peanuts but is mostly known in the US to Spanish-language readers.

One happy contemporary exception is the mononymous artist Liniers (real name Ricardo Siri). For more than ten years, his popular daily comic strip Macanudo has found a large readership among Argentine audiences, blending the charm and humor of Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes with the surreal experimentation of Bill Griffith’s Zippy the Pinhead. American independent children’s book publisher Enchanted Lion Books has so far published three collected editions translating Macanudo into English over the past several years. Liniers has also created two original children’s comics for New Yorker art editor Françoise Mouly’s TOON Books imprint and has also contributed a drawing for that magazine’s cover.

Not content with merely being Argentina’s most beloved contemporary comic strip artist, in 2008 Liniers and his spouse, Angie del Campo, founded the publishing house La Editorial Común. The company’s origins are rooted in appreciation for international comics: “It began because we loved graphic novels that were being published abroad and there was nothing like that locally,” del Campo explained. “We fell in love with a book called El Arte [by Spanish artist Juanjo Sáez], which was published by Random House Mondadori in Spain, and wanted to publish him in Argentina.” It is worth noting that Común’s publication of a Spanish author in Argentina resists the prevailing trend of the past several years, which has seen heavy importation of graphic novels from Spain into South American markets (outside of Brazil); this importation stimulates comics culture but potentially undercuts the development of indigenous publishing houses. “The idea was to create a new channel,” del Campo continues, “to publish local authors, and try to sell the rights abroad, and to import different books by foreign authors, to inspire artists who wouldn’t otherwise have access to this kind of material.” In addition, Común took over publication of Liniers’s Macanudo collected editions, no doubt enhancing the house’s stability.

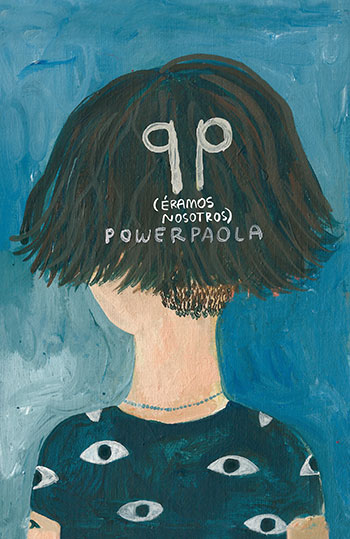

To date, Común has published thirty-two books, approximately two-thirds of which are either local or originally written in Spanish; the rest are translated international editions. Recent and upcoming publications include QP, the new graphic novel by Colombian artist Power Paola; Té de Nuez, by Argentine artist Lucas Nine; Pyongyang, by Guy Delisle (first published in France); This One Summer, by Canadians Jillian and Mariko Tamaki; and Las manos del pintor, by Argentine artist María Luque.

Éditions Matière

Éditions Matière

Montreuil, France

Just east of the 20th arrondissement lies the Parisian suburb of Montreuil, accessible via the Paris Metro and increasingly spoken of as “the 21st arrondissement” or “the Brooklyn of Paris.” Here, out of their home offices, Laurent Bruel and Nicolas Frühauf have run the French comics publisher Éditions Matière since 2004, publishing twenty-four smartly designed, uniformly formatted books spotlighting both French and international artists. Just as Montreuil is apart from—but connected to—Paris, the productions of Éditions Matière seem to stand both apart from, but remain connected to, even the aesthetically expansive world of francophone comics. This has something to do with Matière’s other-media, avant-garde roots. “It all began by making and showing short films in a basement in Montreuil,” Bruel explained. “This continued with a strong commitment to a form of antiphilosophical theory called ‘theorism.’ And became, after some adventures, a publishing house dedicated to publishing books based on the assemblage of images and texts. People call it comic books. We call it popular art.”

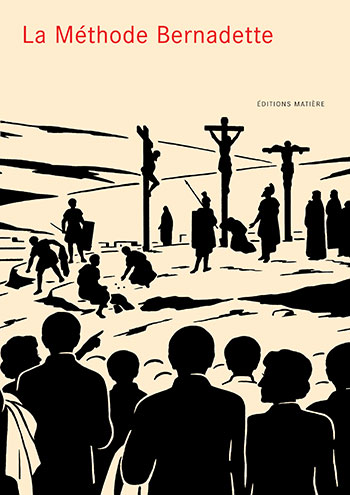

Matière may be best known in France as the francophone publisher of books by Japanese comics artist Yūichi Yokoyama, whose own work (present elsewhere in this issue) radically disrupts the codes and conventions of manga. Similarly, many of Matière’s books assemble figurative images and text within an overall sequence in novel ways. La Méthode Bernadette is Matière’s most surprising book: a collection of striking narrative images produced by a group of French Catholic nuns from the 1930s through the 1960s. In sequences of cut paper silhouettes, originally reproduced on sheets of paper for live narrative performance, the picture stories of the Sisters Bernadette aimed to combat sin, communism, and modernist art in an accessible way until their production was suspended by the Catholic Church in 1969. Matière’s other historical work is the eye-popping Prokon, by Norwegian artist Peter Haars: a 1971 graphic novel that reappropriates clichéd comic book imagery from then-recent Pop Art to tell satirical anticapitalist superhero stories for adult readers.

Which is not to suggest that Matière is dedicated to historical excavation; the bulk of their catalog is contemporary, and the majority is French. Bruel remained sly about upcoming projects, except to note an upcoming book by a contemporary French artist: “It will be graphic, it will be abstract, it will be minimalist. It better be good!”

kuš! komiksi

kuš! komiksi

Riga, Latvia

The kuš! komiksi editorial team embraced internationalism as a way to stimulate a comics scene in Latvia. “In Latvia there were no comics—there were no local comics and also no translations of international books,” said co-editor David Schilter. In 2007 Schilter and Sanita Muižniece initially started an anthology called kuš! (which means “kiss”), featuring in its first issue work by Latvian artists alongside comics by artists from the US, Germany, and Switzerland. “The intention of kuš! was to introduce comics to the Latvian public and to motivate local artists to start to draw comics themselves.”

Eight issues of the kuš! anthology have appeared in the intervening years, but budgetary concerns inspired the creation of another anthology book in a more modest, portable format that permits greater volume and frequency. “The first kuš! anthologies were in a size we thought would be perfect for reading,” said Schilter. “Then came the financial crisis and kuš! was transformed to the smaller š! format (which both means ‘psst’ and reflected the format change).” In an A6 (roughly 4" x 6") full-color paperback format, the efficient š! anthology now typically runs at least 164 pages in length to include original work by many international artists per volume. Twenty-three themed volumes of š! have appeared since the format was inaugurated in 2008. The ninth volume, on the theme of “Female Secrets” and exclusively featuring contributions from an international roster of women, won the Prix de la Bande Dessinée Alternative at the 2012 Festival International de la Bande Dessinée in Angoulême, France.

In addition, the busy editorial team has published thirty-seven volumes in the mini kuš! series, a line of staple-bound full-color comic books at the same size as š!, each featuring a full-length, original work by an international artist. Twenty-three of these are by authors from Latvia or nearby Baltic and Nordic countries, including Lithuania, Poland, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark. All works published by kuš! komiksi are in English, and therefore quite exportable, and the publisher regularly appears at international comics festivals. Their latest initiative is the kuš! mono format, a series of longer A6 graphic novellas by individual authors. The first is by Roman Muradov, a Russian-born artist now living in the US. “The kuš! mono format might be more flexible in the future,” said Schilter. “We’ll have to see how it works out. The developments of kuš! are often more led by chance than by a strict business plan.”

Boomkniga Press

Boomkniga Press

St. Petersburg, Russia

I first met Dmitry Yakovlev, the primary force behind Boomkniga Press, when he was traveling in the US several years ago. He gave me a copy of a Russian independent comics anthology he had published and lamented that nearly all the artists in the book had stopped making comics, moving on to more financially stable fields like illustration and animation. The problem, he explained, was that the Russian comics field, outside of translated American commercial comics and manga, was very small. Judging by his activity, it seems that Yakovlev seeks to build it up almost single-handedly.

Yakovlev’s background is in publishing: he worked for four years as a bookseller and for four years at Samokat Publishing House, Russia’s largest independent publisher of books for children and young adults. But he started his work in comics as a festival organizer. In 2007 he and three colleagues launched Boomfest, an ambitious annual—and still ongoing—comics festival in Saint Petersburg featuring exhibits, workshops, book sales, and artist talks, with an impressive roster of international guests whose visits are supported by various international agencies. International guest artists have included David B., Julie Doucet, Anke Feuchtenberger, Dominique Goblet, Ben Katchor, Joe Sacco, and many others, and they have been called upon not only to talk about their work but to make a broader case in Russia for the value of comics.

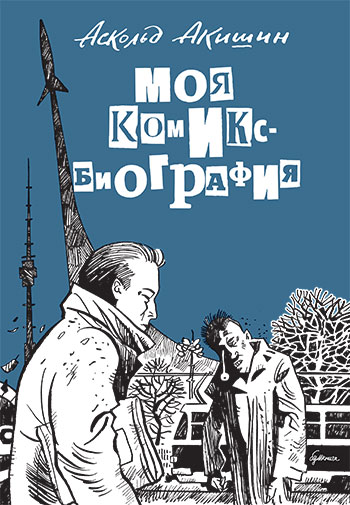

In 2007 the festival spawned a dedicated fanzine, and in 2008 Yakovlev launched Boomkniga Press, a full-bore publishing house. Including issues of the ongoing fanzine, Boomkniga has released fifty publications since its founding. Approximately 70 percent of these are international translations. Because Russian comics publishing is so limited, Boomkniga is able to select rather freely from the international comics scene for its translation projects and has published Russian editions of books including David B.’s Epileptic, Lorenzo Mattotti’s Stigmata, Moomin comics by Tove Jansson, and more. A Russian edition of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis is among the publisher’s most successful books, as is a collection of comics by Russian artist Oleg Tischenkov.

In its 2015 edition, Boomfest ran afoul of shifting cultural pressures in Russia, as an exhibit of collaborative work by Goblet and Kai Pfeiffer at the Nabokov Museum was swiftly shut down due, it seems, to representations of male nudity. Regardless, Yakovlev continues to publish uncompromising work. Boomkniga’s forthcoming publications include translations of Joe Sacco’s Palestine and New Zealand artist Dylan Horrocks’s Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen, a graphic novel about the ethics of erotic fantasy.