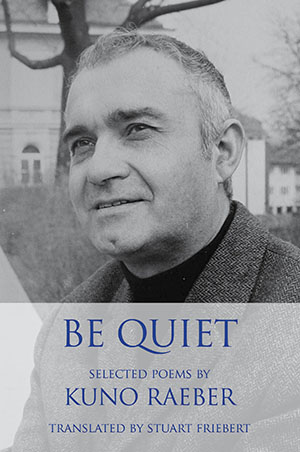

Be Quiet: Selected Poems by Kuno Raeber

Rochester, New York. Tiger Bark Press. 2015. 127 pages.

Rochester, New York. Tiger Bark Press. 2015. 127 pages.

In order to achieve inner stillness, one must first withstand turmoil. Experience of a major world war, a fellow writer’s public rejection of his work, and a spiritual crisis provided Kuno Raeber (1922–92) with enough material to inspire his writing of seven volumes, an occupation through which he worked to achieve calm. This undertaking is reflected throughout Be Quiet, a five-section arrangement of Raeber’s poetic oeuvre as translated and selected by Stuart Friebert. True to the writer’s own collective experience, the compilation illustrates how true quietude cannot exist without clamor.

That clatter is necessary for tranquility encases “Close and Closer,” the first segment of the collection. A poignant first impression, the violent confrontation between the world and the individual becomes evident in “Down with It All,” which shows the casting off of worldly items as a prerequisite to reaching serenity: “all of it down and into the / sudden fall of the water / down and at the end / down with you and me right behind.” The poem summons readers to rid themselves of distractions to achieve stillness. Only when the roar of underwater immersion has taken place can one attain serenity: “the silence the silence the fish / standing open-eyed, its eyes shining in the darkness / taking us both in.” This poem, like so many others in the collection, illustrates that noisy, and often violent, eruptions precede moments of clarity.

Reciprocity between cacophony and repose is likewise mirrored in “But out into,” a poem in the collection’s second section. Much like the first poem in the selection, underwater movement takes place. What characterizes this poem as different, however, is the gradual disappearance of sound; the writer portrays what happens when one slips silently under the surface: “your feet giving way out there and no / sounds of crunching anymore and no / clinking just more / gurgling again / and again the same / vague thoughts.” Instead of granting a reflective ending, “But out into” renders underwater immersion as dubious at best, a repetition of hazy, albeit persistent, thoughts.

Thoughts come and go and repeat themselves throughout much of Raeber’s work, uniting at times a disjointed syntax with a mixed stockpile of religious and natural imagery. Close reading of his poems therefore requires readers to face a turbulent arrangement of both lexis and syntax. The poem “Beetles” explicitly trains the reader in this: “A few beetles vivify / the leaves, freezing in the light . . . Your fingers / trembling suffice, and the leaves turn, die: / be quiet!” This poem, which directly instructs the reader to be still, also scripts no sounds and relies solely on the visual. It also begins with life and ends with death.

Through rich imagery and surprising grammatical constructions, the poems in this collection overwhelmingly show that, while true quietude represents death, tumultuousness leads to focus, to clarity, to life.

Andrea Dawn Bryant

Leipzig, Germany