The Sleep of the Righteous by Wolfgang Hilbig

San Francisco. Two Lines Press. 2015. 163 pages.

San Francisco. Two Lines Press. 2015. 163 pages.

It is gratifying to see Wolfgang Hilbig’s work appear in translation, if posthumously, because of the unique perspective on the former East and the newly unified Germany that he can offer as a genuine representative of the GDR’s “worker class” and gifted writer at the same time. The autobiographical vignettes here span his life from a World War II childhood to the writer’s career in the West.

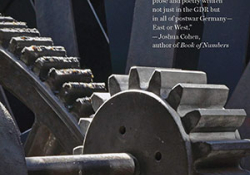

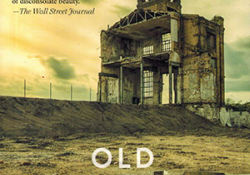

The Sleep of the Righteous is held together by the desolate little coal-mining town of “M.” (Meuselwitz) that he grew up in, with few men remaining after the war, and where he worked for many years. While he has long since moved away, the town lives on in him with all its environmental and political depredations. In the old days it was the environmental pollution created by the lignite coal notorious for smogging up East German skies compounded by the political “pollution” of perennial spying and snitching. Post-Wall, it is the devastating lack of work that gradually empties these towns, compelling any that sought decent incomes to commute to remote jobs in Bavaria to work. If they do have a job, it’s something like “transporting rolls of pink toilet paper . . . from Munich to Leipzig.”

Not only does Hilbig give us a palpable sense of what it was like to live and write under a regime like that of the GDR but also what it was like for those East German adults to lose their whole world to this rush of radical westernization. But as the woman he lives with tells him, all “you people” know is to wait for orders, and “you let yourselves be annexed with the greatest of pleasure.” Once again, they happily took orders.

The last vignette has a Stasi (secret police) operative—whether actual or mere alter ego doesn’t matter—tell him of spying on his life, to the extent that he seems to remember his past better than the narrator himself. And like doubtless many such Stasi spies, this one claims that he was always much more on the narrator’s side than that of the “Firm.” The only way for the narrator to come to terms with his past is to kill this creature and dump the corpse in one of the boilers of the factory he’d worked in. Who’s going to look?

Hilbig’s sometimes surreal narrative makes disturbingly real how much a political regime can truly engender disease, both physical and psychological, by creating these extremes of suspicion and paranoia—never mind the environmental pollution. Isabel Fargo Cole’s finely nuanced translation renders Hilbig’s idiosyncratic observations sharply and entertainingly.

Ulf Zimmermann

Kennesaw State University