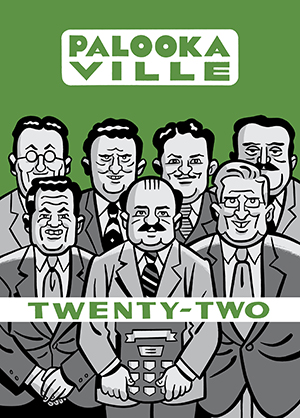

Palookaville, Twenty-Two by Seth

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2015. 120 pages.

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2015. 120 pages.

Abe Matchcard thinks of himself as a “nice, misunderstood, earnest fellow.” He believes this “despite all the evidence to the contrary.” There is plenty of evidence in “Clyde Fans Part 4,” the main story in the newest hardcover Palookaville release by Ontario cartoonist Seth.

Clyde Fans has been serialized in Palookaville for so long now, and Abe and his brother Simon have slowly been revealing their bitter family history for so long, that I forget some of the early details. Abe has lived his sad, salesman life for so long that he, too, has forgotten many important things. He ends up inviting to dinner an old flame whose heart he quite cruelly broke three decades earlier, forgetting the callous end he put to their relationship, having spent the ensuing years focused more on the false, rosy glow of his lying nostalgia for a past that never was.

Nostalgia is Seth’s stock-in-trade. It is evident in every ink line he draws, an aching for an unreachable yesterday so palpable that it creates a similar longing in the reader. Through this signature nostalgic style, he transports us to the fictional town of Dominion, Ontario, home of the Clyde Fans company. (Seth has even created a 3D model of the town for his own reference that is so detailed it not only has gone on the road as a museum exhibit but is the subject of a recent documentary film, Seth’s Dominion.) This depiction of a time and place that is no longer accessible, if it ever existed at all, paradoxically creates a verisimilitude in almost all of Seth’s work, and it finds its ideal expression in Clyde Fans. The charming architecture, clever signage, vintage clothing, and classic cars all tell us something about the world in which the Matchcard family was created, nurtured, and ultimately broken. Simon and Abe inhabit their home, their business, and their lives like genteel squatters, refusing to acknowledge the present and bitterly ruminating on old hurts and ancient defeats that they can’t—or won’t—escape.

The need for Dominion to be mapped out by Seth finally makes sense here, as we see Abe, in flashback, running to one after another of his father’s known haunts (“klop klop”) desperately trying to find him on the day he left the family. Desperate not to be left behind, he never finds him, yet he is left behind, by his father, by the world, left to live within the echoes of a different time, when a traveling fan salesman could make a decent living, although in Abe’s case we wonder to what end.

Does anything we do, good or bad, ultimately mean anything? Does the world remember us? What we remember, as we age, is mostly emotion, attached to memory. Neither are necessarily reliable narrators. Through captions and flashbacks, though, Seth presents us with the truth of Abe’s life, perhaps more true than Abe himself even sees it. Seth’s work is known for its nostalgic warmth, but lying underneath is a razor-sharp honesty. What more could we ask of any art?

Alan David Doane

Glens Falls, New York