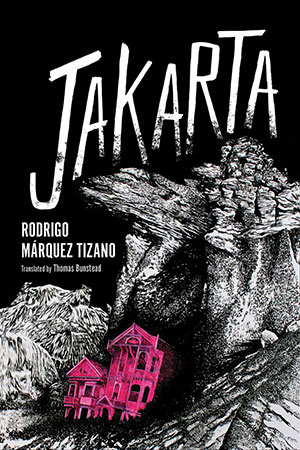

Jakarta by Rodrigo Márquez Tizano

Minneapolis. Coffee House Press. 2019. 160 pages.

Minneapolis. Coffee House Press. 2019. 160 pages.

Jakarta (Yakarta in the original Spanish) is a taut novel set in an unnamed city beset by plague and social unrest, where Mesoamerican traditions (ball sports, mind-set, the sacred function of stone) provide seemingly the only fragile lifelines to meaning. Mosaic in form and function, the novel’s structure suggests the ability to both unify and disaggregate itself. With its lyrical prose, the structure manipulates random and interjecting chunks of color and memory that form the building blocks of a life we hardly want to get to know.

Locked in a small room with his friend Clara, the protagonist (who may or may not be the Morgan he sees in his hallucinations) reflects on the actions of the various Orwellian ministries, principally the Department of Chaos and Gaming, and that of Well-Being, which warn people of unsafe conditions. Jakarta takes place sometime in the future in a nameless city that continues to be ravaged by periodic assaults of plague and a cultural obsession with an increasingly fast and dangerous ball-sport.

The “Bug” (bicho) has made another appearance, presaging another visitation of plague. In theory, he is in a safe place with Clara, a “stone-seeker” who has somehow come upon a monolithic stone that grows to the size of a six-year-old child. But the stone triggers memories and disturbing intrusive thoughts, as it “fulfills two functions, as proof of the overall deterioration, the damage and decline, but also as holder of all our energies.” While in the room with the stone and Clara, the narrator reads excerpts from Morgan’s diaries and reflects on the consequences faced by three populations in the unnamed coastal city that refuse to blend.

Eventually, the protagonist leaves the room and embarks on a journey to a glacier, and he investigates a persistent “heap or bulk” that seems to always appear in his path. In the end, he recognizes the “heap or bulk” as himself. However, instead of the somewhat expected nihilistic outcome, the heap or bulk is more indeterminate, and the novel has an ending that is also a point of departure in the reconstruction of self and reality. Like many novels set in a locked room or cell, the protagonist’s mental state appears to explore madness, but in the end, one realizes the quest is for the truth of all things.

The original prose of Yakarta has a tumbling-over-itself feeling, with words both invented and rearranged, giving it a vertiginous feeling. In such cases, translation is difficult. Thomas Bunstead followed a “fluent” translation philosophy rather than a denotative or literal one, which may have disconcerted the author but which gives the English version an emotional experience authentic to the original.

Susan Smith Nash

University of Oklahoma