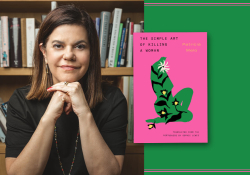

Writing as Spiritual Offering: A Conversation with Leila Aboulela

Leila Aboulela is a Sudanese-born writer who moved to Scotland in her mid-twenties and now resides there, where she writes her critically acclaimed fiction in English. Though her novels have received much attention and praise in the UK, she is less known to American audiences. And yet, post-9/11 and amid our current national climate of fear and division, stoked by a jingoistic and racist president, our country and culture cry out for books like hers—works that painstakingly examine the East-West divide, illuminating the richness and complexity of intercultural relationships through the lives of characters who refuse to be pigeonholed; who remind us that humans are singular creatures who remain united by common needs: for a sense of home, for family, for love. Aboulela’s latest novel, Bird Summons, will be released by Grove/Atlantic in February 2020. It follows three women who embark on a road trip to the Scottish Highlands that transforms into a journey of self-discovery in which the women grapple with the conflicting demands of family, duty, and faith. I completed this interview via email over the course of several weeks in fall 2019.

Keija Parssinen: Tell us a little bit about your journey as a writer. When and how did you discover that writing was something you enjoyed and wanted to pursue?

Leila Aboulela: I was twenty-eight years old when I started to write. So that is late, I guess. I had always loved reading but never felt the urge to write. In university I studied statistics but continued to read literature for pleasure. I rarely spoke about what I was reading. Fiction was a secret enjoyable world running parallel to my life. In my mid-twenties, I moved from Sudan to Scotland. The trauma of that move was the catalyst that launched my journey as a writer. It was as if the person I always thought I would be (a university statistics professor like my mother, a privileged member of Khartoum society) died and a new person was born—someone who was marginalized due to race and religion, a writer without a creative writing degree. I was homesick and could not stop comparing my new home with the old one. These thoughts and emotions couldn’t find any outlet except that of fiction. I felt compelled to write. If you had asked me then if writing was “something I enjoyed and wanted to pursue,” I would have found this wording alien. I was never attracted to the idea of being a writer. My early writing caused me disturbance rather than enjoyment. I was like someone possessed.

Parssinen: Your work regularly depicts the lives of people who have left the Sudan to live abroad, particularly in Scotland. You yourself have made this journey. What is it that you hope to communicate, through fiction, about this experience?

Aboulela: First of all the validity of the experience, of the process in itself. From the host country’s point of view, the life of the newcomer begins when they arrive, and so they are expected to discard their background. From the perspective of the original point of departure, the one leaving is a brave and somewhat careless adventurer; they had better make a success of it, and if they don’t, then they brought it on themselves by leaving! In my fiction, I am looking for a place of compassion, a place in which the traveler can share the baggage they carried with them, a place to hum the yearning for home as well as push forward and claim a position in this new world, which might not be welcoming at first, but, hopefully, there are spots that can give way to the pressure of a stranger rather than resist. Because the immigrant experience is also often one of blunder and misunderstandings, I am also looking for a forgiving place where people can be given a second chance.

Parssinen: I first encountered your writing years ago when I discovered Lyrics Alley at my local library. The lovingly rendered, vivid setting from that book has stayed with me over the years—Waheeba’s hoash, the streets of old Khartoum, the blue Nile. I remember feeling grateful to you for giving me a glimpse of Sudanese history and daily life that was so far from the impressions I had of the country through the lens of contemporary Western news reports. Talk a bit about representing your homeland on the page—the pleasures and pressures of that.

Aboulela: Lyrics Alley, my third novel, is unique in that it is the only one set wholly in Sudan (apart from a few short chapters in Egypt and one in London). It is based on the true story of my father’s cousin, the poet Hassan Awad Aboulela, who at eighteen was paralyzed after an accident while swimming in the Mediterranean Sea. My father was a teenager when Hassan (whom he loved and was close to) was injured, and it made a profound and lasting impression on him. He often used to talk about Hassan, so I grew up with this story. In writing the novel, I added fictional characters and changed many of the details, but I was essentially writing about my father’s youth in 1950s Sudan. This was a time of prosperity and optimism leading up to independence from Britain in 1956. I wrote Lyrics Alley during my father’s last years; I even remember specifically the chapter I wrote while I was caring for him in Sudan. He helped me a great deal with the research, but, sadly, he passed away before the novel was published. To some extent, writing Lyrics Alley was a way of clinging to my father and to his version of Sudan. Without acknowledging it, I felt that once I lost my father, I would lose my “home” in Sudan, my vital living link to the country. Fiction is fueled by love and anger—my love for my father and his own love for his family and country fueled Lyrics Alley.

Parssinen: The Translator is one of the most beautiful and compelling love stories I’ve read. I finished it on an airplane and spent a few moments crying quietly in my window seat! Sammar, who is Sudanese and a devout Muslim, and Rae, who is Scottish, face many obstacles to their romantic harmony, chief among them Rae’s lack of faith. You often write about cross-cultural marriage, but more than a shared culture, a mutual level of religious devotion seems necessary to the marriages’ success. Why is faith such an important bedrock to these relationships?

Aboulela: Thank you, Keija. This is an interesting observation. I have certainly encountered many successful marriages where the partners do not share the same level of religiosity! It might be a cliché, but love does build bridges and brings contrasting people together. However, there can be an element of loneliness—some of it is surmountable and some not. This depends on the source of the loneliness; how vital what is missing is to a person’s worldview and how creative people can be in assuaging the loneliness without risking the relationship. In The Translator, I wanted Sammar and Rae to be soul mates, and this entailed having a spiritual connection in addition to the physical and intellectual closeness that they felt. To me, Sammar is very much the Sudanese “girl next door,” typical in her attachment to religious tradition. To ask Rae to convert to Islam in order to marry her is a daring thing to do, but for her it is the only way their love can continue. A relationship outside of marriage is, for her, not an option.

Parssinen: Speaking of faith: Islam plays a vital role in the lives of so many of your characters, but you also present readers with Muslim characters for whom faith is inherited, where Islam is more of a cultural backdrop than an ever-present influence in their lives. As a practicing Muslim writing in the West, what struggles do you face in representing Islam on the page?

Aboulela: Eurocentric literature is also Christian-centric no matter how much writers and readers regard it as secular or humanist. Every genre from crime to science fiction is heavy with Christian symbolism, while secular literary fiction, even if it is in opposition to Christianity, is also still engaged with its ethos. I write from a Muslim perspective, from within Islamic tradition. Not all my characters are practicing Muslims; many as you say are cultural Muslims, and I don’t find it difficult to write about them because they are people I know and am in contact with.

I am glad that you asked me this question because it supports my view that in literature, the European, white, Christian viewpoint is “normal,” and everyone and everything that is other than that must justify and explain. I wonder if Marilynne Robinson is ever asked what struggles she faces in representing Christianity (or Calvinism) on the page?

In literature, the European, white, Christian viewpoint is “normal,” and everyone and everything that is other than that must justify and explain.

Parssinen: Yes, Robinson is frequently asked about her faith and the Christianity in her books.

Aboulela: She is asked about her faith but without the assumption that putting Christianity into fiction poses a particular difficulty.

Parssinen: I understand what you’re saying. I know any writer writing from a traditionally marginalized perspective butts up against the assumption that he/she/they are the mouthpiece of an entire faith or country. And that’s not an assumption Robinson deals with—westerners understand that a multiplicity of experience is possible within Christianity but perhaps don’t grant Islam the same complexity.

Aboulela: The struggles I face are never to do with representing Islam—this comes naturally and effortlessly to me. What I do take into consideration is the background knowledge of the reader. How much does my average reader know about Islam, how much explanation does he or she need? At the same time, I don’t want to patronize the Muslim reader or those who already know a lot about Islam by telling them what they already know!

Parssinen: Which writers have most influenced your thinking and writing over the course of your career? What are you reading now?

Aboulela: I am now reading Lucy Ellmann’s masterpiece Ducks, Newburyport. It’s amazing to be inside the thoughts of a character in one continuous sentence than runs to almost one thousand pages. The artistry in connecting the thoughts results in an entirely new reading experience. I am also reading An Orchestra of Minorities, by Chigozie Obioma. It’s a love story with an unusual narrator—the chi, or guardian spirit, of the protagonist. I am fascinated by this non-Western feat of storytelling and all that I am learning about the Igbo worldview.

As an Egyptian Sudanese, I grew up with Naguib Mahfouz and Tayeb Salih. Arabic is my first language, and I left secondary school with ninety verses of the epic poem The Mu’alaqa (Hanging Ode) of Antarah ibn Shaddad lodged in my memory. One of the grandest pre-Islamic (Jahiliya) poems, it follows the conventions of its time—starting off with lamenting the departure of the beloved and moving on to boast about the poet’s strength and skills in battle. Antarah’s personal bitterness as the lowly outsider who needs to prove himself ignites these lines into one long, passionate sweep. I often go back to it, and perhaps the cadence and beat of it enters my own English- language writing.

When I moved to Scotland, I discovered Jean Rhys, and she became a haunting influence on my work. So did Anita Desai. As in the case of Jean Rhys, writers who moved to Britain in their youth struck a special chord with me as outsiders grappling with issues similar to my own—Abdulrazak Gurnah, Buchi Emecheta, Ahdaf Soueif. I have also read a lot of Doris Lessing, and her interrogation of human behavior and history always makes a big impression on me. Scottish literature also later became an influence, especially the work of Alan Spence and Robin Jenkins.

My fascination with the idea of home and my intense homesickness led me to accept the Sufi concept of the soul having a spiritual homeland different than that of the physical body.

Parssinen: The theme of homecoming is strong in many of your works, with home being the Sudan. For your characters, the experience of homecoming is often one of both joy and pain. Describe those dueling emotions evoked by “home” and how they inform your storytelling.

Aboulela: Home, like health, is something that we take for granted until we lose it or, at least, experience the threat of losing it. My fascination with the idea of home and my intense homesickness led me to accept the Sufi concept of the soul having a spiritual homeland different than that of the physical body. Our bodies are at home on earth, but our spiritual homeland is the heavens. The yearning that the soul feels is a yearning for its true home and an alienation from the physical trap of the body and the earth it belongs to.

Aboulela: Home, like health, is something that we take for granted until we lose it or, at least, experience the threat of losing it. My fascination with the idea of home and my intense homesickness led me to accept the Sufi concept of the soul having a spiritual homeland different than that of the physical body. Our bodies are at home on earth, but our spiritual homeland is the heavens. The yearning that the soul feels is a yearning for its true home and an alienation from the physical trap of the body and the earth it belongs to.

With regard to my writing, I found that with time my characters started to feel more at ease in Britain. They experienced homesickness less and less and started to behave as if they were citizens of the world. In my new novel, Bird Summons (forthcoming in February 2020), three immigrant women of Arab descent embark on a wild road trip through the Scottish Highlands. Their homecoming experience is a surreal spiritual journey in which objects take on subjective meanings and their bodies experience transformations reflecting their specific dilemmas and challenges.

Parssinen: The number of people forced to migrate from their homes because of climate change or war has grown dramatically in recent years, and in response to these shifts, nationalism is on the rise across the globe, including in America, where Donald Trump infamously enacted a Muslim ban, which was upheld by the US Supreme Court in June 2018. Has this political upheaval affected you, as a Sudanese citizen? What do you think the role of art is in unsettling times like these?

Aboulela: Unsettling times are not a new phenomenon. Throughout history, writers have written during wars, repression, and catastrophes. Art can bring comfort to the afflicted as well as serve a political purpose by interrogating injustice. With widespread Islamophobia in Europe and Trump’s Muslim ban in the US, it is natural for a Muslim voice such as mine to sound political even though that is/was not my intention. When I sit and write, I feel that what I am doing is completely personal. The role of art should be to bear witness to the truth no matter how complex or disturbing or dangerous. I worry that in these polarized times, nuance had been jettisoned in favor of stark simplicity. “You are either with me or against me. You are either onboard or not onboard,” stands in for discussion. With so much distrust going around, writers are fortunate in that readers look up to them for insights and clarity. I believe that the position of the writer is on the rise, and consequently his/her sphere of influence will widen.

Parssinen: Perhaps what I cherish most about your work is its sense of hopefulness—that people can unite in friendship and love despite cultural and religious barriers; that faith, though sometimes abused for purposes of power and violence, is more often beautiful and redemptive; that family bonds, even across thousands of miles, are crucial to our flourishing. Your books, in other words, seem themselves a kind of spiritual offering to your fellow humans. How do you hope these offerings are received? What do you hope your books will do in the world?

I do sometimes think of my books as food that I am serving to readers. A dish full of flavor with a moody texture and the chance shock of pepper.

Aboulela: “Spiritual offering”—that’s a lovely expression. I do sometimes think of my books as food that I am serving to readers. A dish full of flavor with a moody texture and the chance shock of pepper. My characters are flawed rather than “good,” and so different readers respond to them in different ways—sometimes with impatience and sometimes with empathy. Either way I hope that readers feel a mild jolt of consciousness.

October 2019