In the Baltics, a Conflicted Homage to Russia’s Great Poet: The Markučiai Manor Museum in Vilnius, Lithuania

“We’ve treated Pushkin rather well here. We haven’t torn down his statue,” remarks a teenage boy outside the Markučiai Manor Museum in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. In countries dangerously close to the current Ukraine war, anything glorified during the Soviet era is anathema now—including Russia’s celebrated poet.

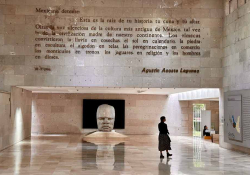

The Manor Museum—which, in 2023, reverted to its historic name after years of being the Alexander Pushkin Literary Museum—is one of a dwindling number of places in eastern Europe where visitors can pay homage to the author of Eugene Onegin and other classics. A historic wooden home where the author’s son lived with his Russian wife, the manor hosts cultural events and outdoor activities. A few yards away from the house, people leave red flowers at the base of Pushkin’s bust, which was sent here from a more central Vilnius location after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The geopolitical issues are ever-present, but the museum and its grounds are worth a trip. Set far back from the main road in a leafy suburb of the city, the house is reached via a lovely woodland path. Behind the manor is a small lake circled by a walking trail. The house itself is well preserved and boasts some of the poet’s own furniture, which his son Grigory brought from the Pushkin estate in Russia. There are manuscripts and books on display, plus artwork by Grigory’s wife, whose family owned the Vilnius property. Tour guides describe the features of each room and how they reflect the mores of the late 1800s.

Indeed, many of the events currently available to visitors are carefully billed as “nineteenth-century”: “board games of the nineteenth century,” “outdoor games of the nineteenth century” (croquet, skittles). There are also tours linked to older Russian writers like Chekhov. “The Markučiai Manor seeks to distance itself from the legacy of the Alexander Pushkin Museum established here during the Soviet era and turns its gaze to the controversial heritage of the Russian Empire in Vilnius,” says its webpage.

Grigory carefully tended his father’s legacy, preserving objects linked to his poetry. One lyric features pine trees on the family’s estate in Russia; when a tree was blown down, Grigory had planks made and engraved with a line from the poem, then brought a plank to the Vilnius house.

Since the Ukraine war began, museum events have included Lithuanian cooking classes, exhibits of “traveling icons of Ukrainian homes,” and sessions on outside writers like Orhan Pamuk. “They had to switch. It’s a survival strategy,” says a museum visitor who is Russian and has lived in Lithuania for twelve years. Atop the house, a Ukrainian flag droops uncertainly next to a Lithuanian one.

A short walk through the Markučiai woods, a tiny chapel (closed) stands near the graves of Grigory and his wife, Varvara. There is even a gravestone for the family dog.

The woodlands are peaceful, but it’s understandable that many Lithuanians are conflicted about whether to tour Markučiai. They argue that cultural remnants of an imperial power—one that is again flexing its might—should, at best, languish unseen. Other visitors to Vilnius will need to decide for themselves.