Translating Buenos Aires Street Slang: 3 Questions for Frank Wynne

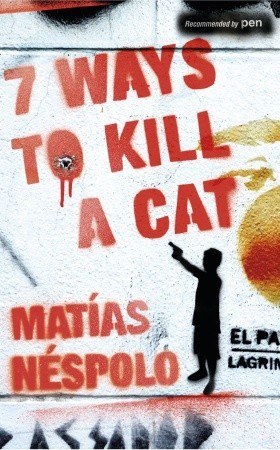

Michelle Johnson: I heard Matías Néspolo speak at the Edinburgh International Book Festival last month, and he praised your translation of his novel 7 Ways to Kill a Cat. He wrote the book in the street language of the Buenos Aires slums. Did this present some particular translation challenges? If so, how did you address them?

Michelle Johnson: I heard Matías Néspolo speak at the Edinburgh International Book Festival last month, and he praised your translation of his novel 7 Ways to Kill a Cat. He wrote the book in the street language of the Buenos Aires slums. Did this present some particular translation challenges? If so, how did you address them?

Frank Wynne: Matías’s novel is set in a place most tourists—or indeed most porteños—would not recognise. The sprawling shantytowns to the south of Buenos Aires are a makeshift world of corrugated iron and timber, crude brick buildings, and high-rise apartment blocks. Matías’s achievement in 7 Ways to Kill a Cat is that he does not describe them but instead creates a collage of sounds, tastes, smells, and music, and in doing so, he manages to conjure their teeming, exhilarating, dangerous vitality.

When dealing with slang, translators are usually advised to stick to what Anthea Bell has called “nonspecific demotic”; that is, a lexical register that is not tied to a particular country or locality. In the case of 7 Ways to kill a Cat, this was both unrealistic and undesirable; the colour and life of the book, and its humanity, come from the crackle of dialogue. I was worried that trying to find an equivalent register for the street slang risked producing something that sounded like an episode of The Wire.

My solution was to use something translators generally avoid—the calque. By preserving Hispanic words, but making their meaning clear contextually, it was possible to keep the clipped rhythm and cadence of the dialogue, something of the flavour of the novel and the sense of “otherness,” which seemed to me crucial. Hence the characters in the translation do not refer to each other as bro, brah, blood, buddy, but as socio, pibe, loco, compañero. Similarly, using constructions like “I’m off my face on coke. Chueco’s fifty-peso bill might have been snide, but it was real enough to get us three grams of merca, and we’ve already snorted the lot,” made it possible to casually gloss words like merca (cocaine), leaving me free to use them again (and to trust the reader to remember).

MJ: Gordon Weetman described your translation as “snappy and inventive, mixing porteño and North American slang to create idiosyncratic gems.” Can you explain this mix and perhaps give an example?

FW: My decision to preserve some of the porteño slang was informed in part by the fact that one of the things I discovered when I first began to translate from Spanish is that it is not a single, homogenous language but one that varies wildly from Argentina to Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, or Spain itself. I felt comfortable creating a hybrid slang since, even in the original, Matías included a glossary of porteño slang since he could not assume Hispanic readers would understand many of the words.

Some of the combinations—“Whatever you’re jonesing for, loco,” and “hijo-de-fucking-puta”—rely for effect on coupling simple calques with English street slang, but elsewhere I elected to translate literally expressions which have perfectly satisfactory equivalents in English. My favourite example is the Argentinean expression (Estar) culo y calzón, meaning two people are inseparable, “tight,” or “as thick as thieves” . . . but thick as thieves is a tired, rather hackneyed expression, and I liked the literal image of being “(as close as) butt and boxer shorts,” but wanted something cruder and punchy, so I translated it: “These days, he and the old man are tight as arsecrack and underpants.”

MJ: Writing for Words Without Borders, Georgia de Chamberet said that “humor, slang, and puns can cause a translator an attack of linguistic hiccups.” Can you recall a particularly difficult expression and how you resolved its translation?

FW: Humour, as Georgia says, is particularly difficult. With puns, a translator is simply forced to find a different combination of words—though in doing so s/he may lose the literal sense of the original. One of the first decisions I had to make in translating 7 Ways was how to deal with the characters who are known not by their actual names but by nicknames—something not uncommon even among adults in Argentina. After much wrestling, I finally decided to leave these unchanged—although the English reader loses something as a result—deciding that, on balance, more would be lost than gained by having characters called Bandy-legs (El Chueco), Blondie (Gringo), Babyface (El Jetita), and The Jellyfish (El Medusa).

But while humour, puns, and nicknames can create knotty problems, sometimes a simple phrase can prove just as intractable when it is repeated by an author for effect. An example in 7 Ways is the repeated phrase por las buenas o a la brava (literally: by force or by fair means). The character Chueco uses it in the opening scene to describe two ways to kill a cat, but Matías tellingly echoes the phrase in the last chapter, both when the police ask the crowd to disperse and in the last sentence of the novel when Gringo describes the impending riot. Eventually, I translated the expression as “in a civilized fashion, or like a fucking savage.” Translating por las buenas as “in a civilized fashion” produced an English expression that I felt worked for Chueco’s grim lesson in butchery, for the order given by the police to “disperse in a civilised fashion,” and for the narrator’s bitterly ironic last words about the vicious beating that is about to happen: “Now things are really kicking off. In a civilized fashion . . .”

Frank Wynne (www.terribleman.com) is an author and translator from both French and Spanish. His translation of Michel Houellebecq’s Atomised won the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award 2002.

Michelle Johnson is WLT’s managing editor.