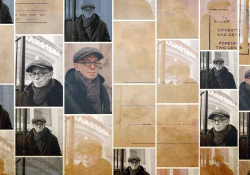

Translation at the Movies: A Conversation with Antonio Skármeta

Many works of Chilean writer Antonio Skármeta have formed the foundations of further artistic endeavors, including and beyond their own translations. His 1985 novel, The Postman, inspired both Michael Radford’s film Il Postino and Daniel Catán’s opera of the same name. More recently, his unpublished play, El Plebiscito, provided the basis of No, Pablo Larraín’s highly acclaimed film about the 1988 Chilean referendum to oust dictator Augusto Pinochet. Now, yet another of his works is set to receive the movie treatment: his short, intimate 2010 novel, Un padre de película. The novel appears in English translation today from Other Press as A Distant Father, and the upcoming film by Selton Mello will be called A Movie Life. I spoke to Skármeta about A Distant Father and seeing his works both in translation and on screen.

Arthur Dixon: You’re a translator in your own right—you’ve worked with books by Jack Kerouac and F. Scott Fitzgerald, among others—and in A Distant Father your protagonist is a translator, too (if only part-time). How would you describe the experience of writing about a translator and then seeing his story translated?

Antonio Skármeta: Back in the days when I was young and I translated American novels into Spanish, I had already published my first book, and in the frenzy and innocence of youth, I felt that literature was the most important thing in the world and that all the writers in the world—from the classics to the child at the school on the corner who invents a poem to flatter his teacher—deserved my devotion and brotherhood.

During the time when I was translating a work, it felt like the author was a neighborhood friend or a college classmate. I was so sensitive to what the other author had written that I strove to make it sound as expressive in Spanish as it had in the original.

Translating would send me into a trance and detach me from the daily diversions of being young. But every time I finished a job, the doubt of whether or not I had found the right tone and formulation would stay on my mind for a long time.

The protagonist of A Distant Father chooses to be a secondary character. He doesn’t feel quite like a protagonist. Everything emphasizes his fragility and his modesty. He’s not a writer but a translator. In terms of love, he is as innocent as the schoolchildren he teaches. In terms of family, he has been as abandoned as his own mother. When, in one moment of the novel, Jacques sees a little child in a baby carriage who’s not with his mother, he feels intense compassion for him, and he makes a decision that I think elevates the emotional volume of the story.

AD: How does historical context influence A Distant Father? Do you see the novel as representative of Chilean history?

In A Distant Father, I felt an intense need to submerge myself in the intimacy of people who live in an imprecise time and are not harassed by the dragons of modernity that, with their gigantic volume and their guttural communication, pay no attention to the big-little issues that afflict people of all times and places.

AS: The long history of Chile, with its eruptions and its political tragedies, is not present in A Distant Father. I’ve addressed those situations in my own way in other novels that have been translated into English, such as I Dreamt the Snow Was Burning, The Postman, The Dancer and the Thief, and The Days of the Rainbow. But in this work I wanted to move to somewhere far from the great commotions of history. I felt an intense need to submerge myself in the intimacy of people who live in an imprecise time and are not harassed by the dragons of modernity that, with their gigantic volume and their guttural communication, pay no attention to the big-little issues that afflict people of all times and places: family relationships, love and lack of love, creation, identity, faithfulness and betrayal, the fleetingness of life and its meaning. If the expression is valid, A Distant Father is an “unplugged” novel.

AD: How will the changes in setting chosen by the Brazilian production team affect the film based on A Distant Father, which will be called A Movie Life in English? This won’t be the first time another artist has changed contextual elements of a work of yours; the same thing happened with the film Il Postino. As the original artist, what do you make of such changes?

AS: It’s impossible to predict how the film will be, as the script was only recently finished and filming is planned for 2015. However, the small towns of Latin America, isolated from the capitals of their countries and certainly even further from New York or the European metropolises, are a great reserve of authenticity and purity. Their distantness and smallness create mythical inventions, overflowing urges. The small town encloses passions and conflicts in a sort of pressure cooker.

The film will be shot in the south of Brazil, and I’m sure it will capture the beauty of the region, the ease and tenderness of its people, and the music of the era. I can tell you in advance that the father in the film will be from the United States, not France, and there will be American poetry—to start, by Robert Frost.

As a writer I feel it’s an enormous privilege that great directors are interested in adapting my novels to the screen, and I repay them for their interest by giving them all the freedom their expressive needs require. My work should be the platform from which the fantasy of the director, the composer, and the actors takes off toward other horizons.

AD: Could you compare the experience of seeing a book translated to that of seeing it made into a film? How similar are the two processes?

AS: In other cases, such as those of Il Postino or No or The Dancer and the Thief, in the books’ many translations I recognize the vivacity of the original prose. The best test is to read translated chapters in front of audiences that speak the other languages in question. I do this in the languages that I know—English, French, German, and Portuguese—and the listeners react the same as when I read for Spanish-speaking audiences. In the case of films, the difference is exactly what I appreciate most. To see how, coming from the same source, the product is something else.

AD: You have plenty of experience with the transition between writing and film and vice versa. What is lost during this transition? What is gained?

AS: Something of the story’s intimacy is lost, the allusion to intangible things, the secret of an atmosphere. But the performance becomes more powerful: the shadows are illuminated, the music is really heard, the actors “play” with their roles and fill them with another energy. If reading is a secret conversation with the reader, film is a tribal ceremony in which the audience recognizes with stimulating immediacy the elements that unite the spectator’s life with the heroes of the screen.

If reading is a secret conversation with the reader, film is a tribal ceremony in which the audience recognizes with stimulating immediacy the elements that unite the spectator’s life with the heroes of the screen.

AD: Should the author of the “source text” be involved in the making of a film, alongside the director? What about in the making of a translation?

AS: There are authors who follow both processes step-by-step and jealously take care that things are exactly how they conceived of them. I stay out of everything—except when they ask me something—and I’ve never been disappointed.

AD: El Periódico de Catalunya described A Distant Father—correctly, in my opinion—as “poetic.” How will the “poetry” of the book translate to the screen?

AS: Precisely what is “poetic” about the book is that elusive nature which hlights up every dialogue and image and escapes the detail of rationalization.

AD: What are your favorite films based on books, and why?

AS: I have dozens. But to name one, I’d say Cabaret. It captures the spirit of Christopher Isherwood’s work, Goodbye to Berlin, and the synthesis of performance with the rise of fascism in Germany makes for an intelligent, profound, and seductive film.

Translation from the Spanish

By Arthur Dixon