The Form Read Round the World: American Short Fiction and World Story

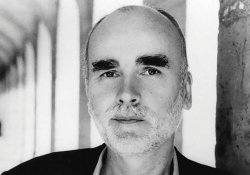

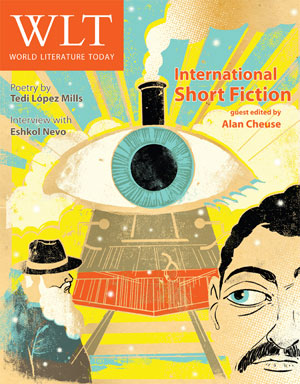

The editors of WLT were deeply saddened to hear the news of Alan Cheuse’s passing last week at the age of seventy-five. Dr. Cheuse served as a juror for the 1994 Neustadt International Prize for Literature, nominating Norman Mailer for the prize, and for several years (2005–2009), WLT reprinted many of his reviews and tributes from All Things Considered in the print edition of the magazine. The following essay introduced the “International Short Fiction” special section in the September 2010 issue. The story that inspired Edel Rodriguez’s cover illustration for the issue, Ana Menéndez’s “You Are the Heirs of All My Terrors,” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize that year.

We’ll never know when the first preclassical rhetors or Homers sounded their earliest invocation to the Muse on the air of antique Greece. That event is lost to us in time, and only some gifted fiction writer can give us a hint of what that moment out of the prehistoric past may have been like.

Living here in history full-blown as we do now, we can confirm some facts about the origins of a much more recent literary form—the modern short story. We know that on such and such a date in the early nineteenth century, the editor of Blackwell’s magazine in London published a story by Edgar Allan Poe, thus bringing to the potential reading public of England, Europe, and America the first of a long line of commercial fiction. Slightly older than Poe, New Yorker Washington Irving had in 1819 published his “Rip Van Winkle” in the first volume of The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent, a hardcover collection of tales, and a year later, in a subsequent volume of this same series, he brought out “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” Hawthorne published his early tales in book form as well. James Fenimore Cooper published his first novel that same year.

But of all these American writers it was Poe, bent with his raving genius, his drinking problem, and his money problems, who determined to eke out a living from publishing short fiction in small commercial magazines, some of which he eventually edited. He worked at this labor some decades before Europeans such as Gustave Flaubert and later Guy de Maupassant had settled on the short-story form as a vehicle for making art that coincided with popular entertainment. More than half a century after Poe’s death, the young Russian physician Anton Chekhov began publishing his first humorous sketches in Moscow literary magazines and, subsequently, a long string of short prose fiction about everyday life that most American writers identify as the model of the modern “art story.” Ironically, our man Poe arrived at the form decades before.

*

Here it might be wise to stop for a moment and meditate on the brevity of the history of the modern story. It’s a blink of the eye compared to the long gaze of the epic. Ever since the advent of the Homeric epics with their anecdotes and tale-like narratives within the larger poem, what we call “tales”—accounts or brief narratives of an event, sometimes delivered with imaginative flair—as opposed to stories, have been in plentiful supply, from the Bible to Chaucer to Boccaccio. In those brief narratives embedded in narrative poems, the source remains self-evident—all belong to the overall narration. In Boccaccio, we read tales recounted to us by the narrator. Folk tales come to us out of that great mist we think of, because it is easy to do so, as the popular culture of the time.

What distinguishes all this traditional short fictional narrative from the modern short story? The nature of the art work itself. The anecdote, the fable, the folk tale—all would entertain us and, ultimately, call our attention to some moral problem or founding event in what we take to be the world of gods and history. The modern story writer, from Poe onward, seeks to create a work of short fiction that, like a lyric poem, has no immediate tie to the culture in which the writer works or to the history of his or her time. All reference to the everyday world comes by way of analogy only. The art story, as I would like to call it from here on out, is a discrete creation that possesses its own aesthetic, by which it stands or falls. We connect it to actual life in the same way we do a poem or a painting—as I mentioned, by analogy.

Looking at this from another angle, we can see that simply identifying the modern short fiction maker as a writer propels the genre into a new realm. All the myths and brief anecdotal narratives from Homer onward through the late Greek and early Roman period (except perhaps for a maverick work of prose narrative such as given us by Apuleius) clearly belong to a larger story. All else that’s come before it has its root in myth or history or theology or (in the case of Boccaccio), as we get closer to our own age, what we might identify as anthropology or sociology or psychology. These older tales and stories seem to have an end other than the satisfaction of pure aesthetics—whether it is to prove a point about morality or history or the lives of city people trapped in a country setting during a time of plague.

Poe changes the direction of short narrative. He takes what otherwise might be the traditional “tale” and transforms it into a prototype of psychological fiction. Taking a cue from his own aesthetic for making poetry, he writes stories whose goal is entertainment at the highest level—stories that he hopes will serve as beautiful creations in and by themselves. His mystery stories, or his so-called ratiocinative fiction, also keep to a singular form, with the end in mind of immediate entertainment. Pieces such as “The Fall of the House of Usher” work beautifully in themselves and as illustrations of the aesthetic Aristotle holds up as a standard in the Poetics—the dramatic work that moves from establishing a goal to struggling to attain that goal to the final recognition or revelation.

I don’t know any other major art form except perhaps modern dance that matured so deeply within the span of a hundred years. From Poe to Hawthorne to Flaubert to Maupassant to Chekhov and back to the United States, the modern short story came into its full growth.

If we hold that up as a standard, we can see that much of European short fiction before Chekhov does not always keep to the highest level or form. Once he moves from his early comic sketches into the realm of his psychological studies—taking the cue from his training as a physician, I would call them “clinical” studies—of human desire and the attempt to achieve some desired goal, Chekhov presents us with a full-blown paradigm for the modern short story. James Joyce learned from him as did, in America, Sherwood Anderson, William Faulkner, and Ernest Hemingway. I don’t know any other major art form except perhaps modern dance that matured so deeply within the span of a hundred years. From Poe to Hawthorne to Flaubert to Maupassant to Chekhov and back to the United States, the modern short story came into its full growth.

American story writers know this legacy of the art story as opposed to the popular story, though now and then, in golden periods of American publishing, the two varieties of story have overlapped. The art story, as received in the United States by Anderson and Hemingway from Chekhov himself (in translation), and Chekhov by way of James Joyce, is a discrete creation that, like a poem, is linked to reality by means of analogy rather than literal truth, or, as Marianne Moore puts it in a poem about poetry, good short fiction presents us with “imaginary gardens with real toads in them. . . .” To put it another way, in a world in which the ones and zeros of information flood over us more and more each day, short fiction remains an art of the analogue.

*

Though at the beginning of his career Ernest Hemingway was much more in debt to Sherwood Anderson than he ever wanted to admit, the pair of them clearly owed their aesthetic sense of how the short form works to that line going back to Joyce and Chekhov. Hemingway, the genius of the modern story in English, passed this legacy along to literary cultures around the world.

Allow me to make some large judgments here. By the post–World War II period, a short-story revolution swept around the world, making it clear to writers from Finland to China and points in between that the art story stood as the full-blown expression in the short form of what any serious modern writer believed about his or her aesthetic. In some places, say, New Zealand, when Katherine Mansfield began to work, the writer’s goal was to create a story in the spirit of Joyce and Hemingway. In other parts of the world, say, in Egypt or Iraq, the aesthetic news about the gold standard of the modern short story came by way of a generation or two of European writers who owed their aesthetic sense to Hemingway, Joyce, and Chekhov. Graham Greene, mentor of the watershed Indian story writer R. K. Narayan, invoked Chekhov when first recommending him to his publisher in England. Hemingway could not be far behind.

The question of “influence” is always a vexed one. Critics can always come up with a fine writer who claims never to have read the masters whom we think of when we read him. Raymond Carver, the modern American master of the short story, always found himself a bit bemused when told by younger writers that he had influenced them heavily. “Read the people I read, Sherwood Anderson and Hemingway,” he would say. “You should look to them, not me.” So while influence is a vexed question, it is also a subtle problem.

Read, for example, some of the stories we have collected for you in this issue of World Literature Today, and you can easily sense the shape and form of the short story that has come down to the current generation of fiction writers over all the generations from Hemingway and Joyce and Chekhov. Even if some of the writers have not read any of these writers—difficult to imagine but always possible—they have read, and clearly will have found use in, the work of writers who have. I know this sounds tautological, but the freedom of the contemporary short story evolved in much the same way that modern Western political revolutions evolved—if not directly from the American Revolution, then from subsequent revolutions, such as the French Revolution, that looked to the American event as epoch-making.

Read, for example, some of the stories we have collected for you in this issue of World Literature Today, and you can easily sense the shape and form of the short story that has come down to the current generation of fiction writers over all the generations from Hemingway and Joyce and Chekhov. Even if some of the writers have not read any of these writers—difficult to imagine but always possible—they have read, and clearly will have found use in, the work of writers who have. I know this sounds tautological, but the freedom of the contemporary short story evolved in much the same way that modern Western political revolutions evolved—if not directly from the American Revolution, then from subsequent revolutions, such as the French Revolution, that looked to the American event as epoch-making.

That’s how I see the Hemingway short story, as epoch-making, with, to use Ezra Pound’s valuable paradigm from his ABC of Reading, Chekhov as the inventor and Hemingway as the master of the form. The shock wave of Hemingway’s mastery reverberating around the world, with undertones and deep resonances of Chekhov, has brought us to where we stand today, as readers and writers alike.

*

Or where we sit, holding this issue of World Literature Today in our hands, about to enjoy a sampling of the fictive worlds conjured up by nearly a dozen writers from around the globe, all of whom work with the modern model of the art story, all of whom hope to meld the modes of entertainment and wisdom into a singular narrative line. Some read thoroughly in the modern narrative tradition, hewing to a clear story line, as in, for example, Sri Lankan writer Ru Freeman’s “First Son” and Canadian-born writer Alix Ohlin’s “The Cruise.” Others, such as Cuban American writer Ana Menéndez in her beautifully dreamlike “You Are the Heirs of All My Terrors” and Benjamin Percy in “The Roof People,” produce visionary variations on the straightforward tradition. From the steamy streets of Kuala Lumpur to African beaches to Europe’s thoroughfares, families and errant ghosts, lovers and neighbors, poets and fugitives make up the crowded population of these worlds. As diverse as they are, these stories point up that serious fiction writers accept the legacy of the modern short story and brilliantly turn it to their own purposes, which means, ultimately, that they turn it to our purposes—aiding and abetting our desire to know the intricacies of national differences and to participate, at the same time, in the kinship of common earthly concerns.

Washington, D.C.

Editorial note: From the September 2010 issue of World Literature Today.