Across Time and Two Hemispheres

In honor of Nadine Gordimer, who passed away yesterday at the age of ninety, we reprint here her testimonial from our Winter 1996 issue, devoted to “South African Literature in Transition.” Susan Sontag nominated Gordimer for the 1988 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

When I was sixteen or seventeen—distant youth blurs; years that must have been so distinct in experience become fused—two books invaded with exhilarating possibilities my narrow life in a South African mining town. One was E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, the other was James Joyce’s Ulysses. (Marcel Proust was to come a little later, with an education in the pains of love between men and women, women and women, men and men.)

In Forster’s novel it was not the mystical experience of Mrs Moore in the cave that engaged me—I was too young for ontological distress—but Fielding’s gallop around, towards, and away from Dr Aziz, and the two words: “only connect.” I was becoming aware of my growing up in a society, my country, where there was no connection recognized between ourselves, the whites, and the surrounding blacks. A world of strangers. (And that was to become the title of my second novel, about fifteen years after.) Only connect: was it possible, for me, for us? And that word only: did it mean that was all there was to it, something easily achieved, or did it mean that it was the exigent, the “only” possible solution—and to what? To a situation into which I had been born? Through Forster I began to have an inkling of understanding of my place and time, the world around me.

In Joyce’s novel it was an internal world that was opened up. Salman Rushdie said recently, “One of the things a writer is for is to say the unsayable, to speak the unspeakable.” Joyce was the writer who did this for me, making the inner connections between sexuality, sensuality, the biological facts of being female, even the humble functions of elimination, with what I’d been taught were the higher emotions, the ones it was “decent” to express. Joyce brought self-acceptance to the turmoil of adolescent emotions.

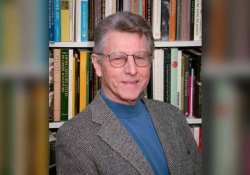

But the contrast between those two different, wonderfully illuminating works of fiction brought into question another kind of connection—a question that roused whatever burgeoning intellect I had. Both books were works of the writers’ imagination: how did the imagination work, what were the connections of literature, deep in its source? Forster was transparent, Joyce was difficult and devious, yet both came from there. I had to start with what seemed to me the difficult one. In the municipal library I found a book entitled James Joyce: A Critical Introduction by Harry Levin. It was the first book of literary exegesis or criticism I had ever read. It was such a revelation to me that I then bought my own copy. I have it still, on the shelf beside all Harry Levin’s other works, a small book that stands, in my mind, at the wide doors it opened for me. How lucky I was to discover literary criticism through Harry Levin and not through others who shall be nameless, whom I had to read when, in my twenties, I followed some Eng. Lit. courses at a university. Harry Levin was the one I read for the pleasure of his lucidity, the grace which came from the searching understanding that is the true expression of love of literature, and which he offered in such abundance, with such wit and keenness, lack of scholastic exhibitionism, wearing his polymathic erudition like a well-cut comfortable jacket. On Shakespeare (with incredible, unflagging freshness), on Melville, on the French realists, and with Grounds for Comparison, Memories of the Moderns, and the wonderful Playboys and Killjoys, that intriguing explanation of comedy, he has remained my lifetime mentor, the answer of something called comparative literature studies to the old question of my youth: what are the connections of the intellectual imagination, which he defined, in his preface to Refractions, as “interrelationships—traditions and movements, the intellectual forces that find their logical termination in -ism . . . looking at literature as one organic process, a continuous and cumulative whole.”

But I am running ahead of myself—the young girl with her first purchase of a book of literary criticism, James Joyce; Professor Harry Levin, the author, of Harvard University. I had never been out of Africa, neither to the Europe of my parents’ respective origins in England and Latvia, nor to America, and this august personage (had I ever met a professor?) was someone to whom I could not put a face, although his voice was one that I heard—real writers are distinguished by being heard clearly through the cadence of their prose. Never, even if granted the reincarnation of several lifetimes could I have ever imagined myself as someone who could know a Professor Harry Levin, have met him personally.

But this magician of hermeneutics was to be connected, again, with an innovation in my life.

I am thirty-one years old, have published several novels and story collections, and am about to attempt to overcome my nervous terror of standing up to speak in public, although I always have been talkative enough in private. I have accepted an invitation to give the Ann Radcliffe Lecture at Harvard—my first public lecture. It is entitled “The Novel and the Nation” and deals with the interrelation of nationalism, national politics, traditions, and social mores in African literature. Across seas, continents, and the vast cultural chasm between the seventeen-year-old from the South African mining town and the distinguished Irving Babbitt Professor of Comparative Literature at Harvard, I meet Professor Harry Levin. He is a tall man with a narrow patrician face, a perfect brow, and blue eyes whose lovely gaze is at once intense and gentle. The professor is handsome, the professor is friendly, and as if he were not blessed enough, the professor has an enchanting Russian wife, one of those rare individuals with whom you know at once you may dispense with trivial exchanges.

When I returned to the United States, perhaps a year later, I felt welcome to contact the Levins again; and that was the beginning of a long and special friendship that was to grow across time and two hemispheres. I hope I am not claiming too much for myself when it takes my fancy to see that friendship as a symmetry humbly matching, in a personal relationship, the passage from one culture to others that was the thesis of Harry Levin’s intellectual range. The professor quickly became Harry, but the familiarity established through subsequent meetings over thirty years never diminished in any way the homage I paid—and pay to this day—to a brilliant mind unsurpassed by any of his contemporary literary scholars. As for Harry’s personality, I find it significant—looking at the shelf of his works, with his printed name there, sometimes on a worn paperback, sometimes in gilt on a fine edition among his gifts to me—to note that he saw no need to use a middle initial as so many Americans seem to feel necessary for identification; indeed, he used the informal version of his name, instead of “Harold.” This man of many cultures remained serenely confident of his identity as an American. Although he travelled and sometimes even lived abroad on sabbatical or to fulfil prestigious appointments—at Oxford University, for example—he had no need of exile to become part of, a partisan of, world culture.

On my visits to America it has been my jealously guarded privilege to keep aside from any obligations a couple of days to spend with Harry and Elena at Kirkland Place. I have happy memories of trips with them. Wellfleet, where Harry lies now, I had heard about so vividly—it was in the fibre of their life that when they took me there for a few days I found the old house, the long walk along the sandy path through scrub, the odds and ends of seafaring past come upon, and the glorious natural highway of sand along the sea all recognizable rather than seen, at last, for the first time. On the way, of course, we stopped off at a secondhand book store the way another kind of appetite might make it necessary to stop off for a hamburger. (Not that we neglected the pleasures of lobster, later.) On a different occasion—I think it was the official opening of the W. D. Howells House—I went with the Levins to Kittery Point, learning from Harry about his former teacher and friend, F. C. Matthiessen, and so, as often in Harry’s company, was introduced to the work of a writer I hadn’t read. In Cambridge itself, Harry would always keep in mind museums and art exhibitions that would interest me, and we would stroll round to see them together, my enjoyment expanded by his insights.

Sometimes the visits to Kirkland Place have coincided with some commitment in Cambridge. Harry’s and Elena’s pleasure at my receiving an honorary doctorate from Harvard in the Eighties was important to me. We even could look back on a bizarre time together, during the period of student uprisings in the late Sixties, when I was due to give a lecture (more confident about such things by then) at Harvard. Harry kept protectively close to me in case, surrounded as I was by that then beleaguered breed, the academics, we should be chased ignominiously off the stage. He had noted the nearest exit by which to escape student wrath. There was also the possibility that my identity as a white South African would make me a specific target for anti-racism, without my having much chance to establish my credentials as an anti-apartheid activist at home. And the other possibility, of course, was that no-one at all would turn up to listen to me. The Yard was in turmoil. Who was interested in lectures! I think we rather hoped this last would be the case and we could go back to Kirkland Place to sit at the round table in the cosy kitchen for our evening aperitif, Harry with his vodka, me with my whisky.

But there was an audience: perhaps forty dutiful defenders of the right to pursue their interests no matter the disruptions of the period. On the balcony I saw at once, with foreboding confirmed, a large young man: dreadlocks, booted feet up on the barrier as if directed right at my face. All the time I was speaking I had my eyes on him, a mouse watching a crouched cat. I concluded my discourse. One of the writers whose work I had discussed was the Kenyan Ngugi wa Thiong’o, in whose novel The River Between there is a conflict, in a young girl’s life, between the edict of her Christian conversion against the practice of female circumcision and the traditional edict of her society that a girl cannot become a woman without the ritual performance of this mutilation. While—after the polite patter of applause, the chairperson announced that I would take questions—I gazed bravely to face the pounce from the balcony, the proverbial little old lady stood up in the front row and piped, “Miss Gordimer, what exactly is female circumcision?” With tremendous relief, I was able calmly and clinically to reply, “Excision of the clitoris.”

Puzzlement melted the attention of her expression, fixed on me. Harry, the chairperson, all of us positively heard the next question forming in her mind, about to reach the tip of her tongue: “Miss Gordimer, what exactly is the . . .” With swift presence of mind the chairperson (could it have been Professor Bloomfield?) launched into the obligatory words of thanks to Miss Gordimer for her interesting and informative etc. And as Harry and I joined Elena and left the hall, the dreadlocked young man came up to say how much he wanted to meet me because he had read and enjoyed my books.

Harry, Elena, and I have recounted that evening to one another many times, laughed again and again in speculation—who in heaven’s name could that old lady have been?

Conversely, there were the personalities local and in the wide world who were Harry’s familiars—writers whom I knew only through their work, and about whom and their work he was endlessly illuminating. Delmore Schwartz’s The World Is a Wedding had been one of the cult works, even vaguely influential during my lonely apprenticeship as a writer. When Harry and Elena were young, they had shared a house with Schwartz and his wife. Harry would relate Schwartz’s tragic personality to the essence of his work. To the Finland Station had been part of my political self-education; The Company She Keeps had answered my own rebellious independence (and my intellectual pretensions) as a young woman—Edmund Wilson and Mary McCarthy had been part of the Levin set, part of what I think of as the Partisan Review circle of a vigorous era in American literature, cosmopolitan culture, and independent thought. The kind of circle in which, today, if it existed, a new Left might have some hope of rising out of the failure of Communism and the consequent hubris of capitalism. . . . Harry’s insights into the work of his friend Nabokov, our long discussions about Thomas Mann, and the grand keyboard of literary cross-references that was so easily at Harry’s command when lesser writers came up—Harry had read, continued to read, was reading everything—was played round the kitchen table, a magic enclave where my mind rejoiced. In that house, the free play of intellect was as natural as the scent of flowers or the flavours of good cooking; that kitchen, although the other roomsful of books in the house were endlessly beguiling, was—and is—my favourite place in the United States.

Ours was a literary friendship.

Elena commenting wisely from her rocker, Harry in the midst of journals and newspapers: that round table in the kitchen was my Algonquin in the company of Proust, Joyce, Hawthorne, Melville, Shakespeare, Fitzgerald, Mishima, Musil, Tolstoy, Turgenev—all, all, and the characters they created, all, all our shared familiars. There was our exchange with the ideas of the time we shared, and the time Harry knew before mine; there was the edge of literary gossip, for Harry Levin had a flick-knife within his wit that now and then would shave a sliver off a reputation. Yet this never damaged what was real, genuine in a work. I don’t know if Harry had any religious beliefs (I must ask Elena)—probably not, else why would we not have discussed them, as we did almost everything in human experience? Literature was his belief; the power of the human imagination to transform the limits of the intelligence, surpass apparence, and approach the mystery, the how and why of our existence. As a critic, I think he had (yet another) rare quality, a grace in the sense of a benefice: he was not an imaginative writer manqué. He was not secretly jealous of the imaginative writer, as one detects so many critics are. He never, in his evaluation of a work, gave one the impression that he was really rewriting it the way he would have, and thinking it better. In one of my notebooks I quoted something he wrote, of himself, in A Personal Retrospect: I knew I lacked that special concentration of the ego which enables the truly imaginative writer to discover the powers within himself.”

Ours is a literary friendship; that is what I still have, living, although the confidences I eased my spirit with in the other aspects of our firm friendship belong with Elena alone, now that he has gone. The literary friendship remains alive, between Harry and me, he as the author, I as the enchanted re-reader of his books.

Johannesburg

From World Literature Today 70, no. 1, South African Literature in Transition (Winter 1996), 111-114