10 International Dystopian Novels about Authoritarian Regimes

When things are bad, I like to read books where things are even worse. In 1516 Thomas More imagined an island with an ideal society and coined the term “utopia.” Little did he know that a few centuries later, various authors would devise a counternarrative—the worst of all possible worlds—namely a “dystopia.”

Dystopian literature saw a rise during the twentieth century, which was prompted by a spike in totalitarian states and a series of devastating wars plaguing the period. Writers like Huxley, Orwell, and Zamyatin envisioned their societies in the future of oppressive governments and eccentric dictators taking complete control over the lives of their citizens.

In the twenty-first century, there is still an undercurrent of politics in dystopian literature. Rapid changes in the world alarm readers who want to know what the future erasure of history, religious extremism, extreme class divisions, and women stripped of their human rights might look like. Most importantly, they wonder how to survive in a world like that. In dystopian literature, there’s rarely a happily ever after (if there is an ever after at all), but authors provide their readers with hope—a hope that if they engage critically with their reality, they might avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.

It’s that time of the year when you want to bask in the sun, have a picnic on a meadow, and read about Big Brothers and conditioned baby embryos. Oh no! You have already read all the well-known dystopias. What to do?! This list is for those who want to dive into some new anti-utopias as envisioned by authors from all around the globe.

Argentina

Agustina Bazterrica

Agustina Bazterrica

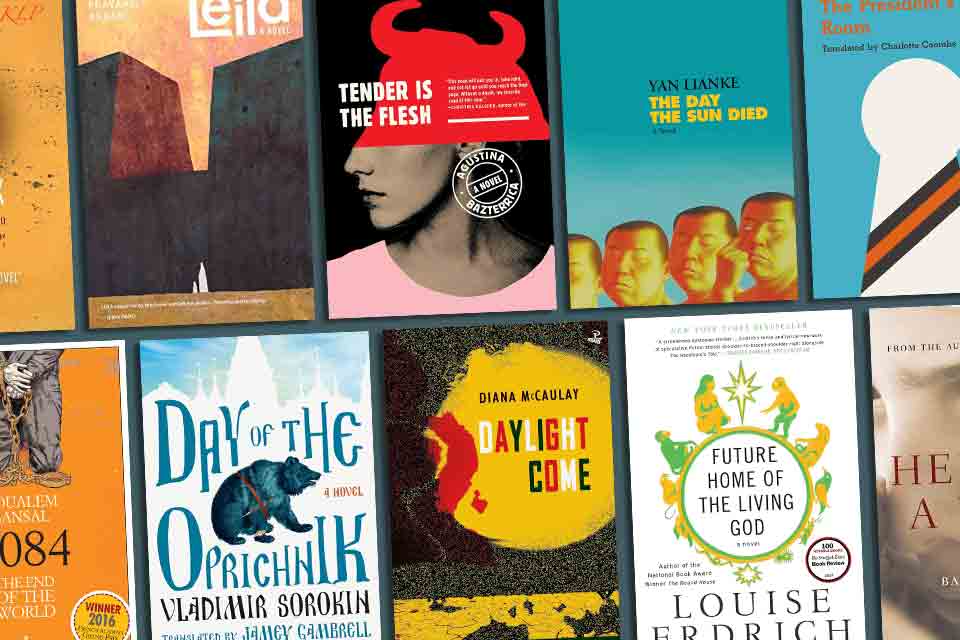

Tender Is the Flesh

Trans. Sarah Moses

Scribner, 2020

Animal meat, contaminated by a virus fatal to humans, is no longer edible. In Bazterrica’s novel, the world undergoes a “Transition” in which the government legalizes and institutionalizes cannibalism. We see the Orwellian doublespeak as the state replaces words like “assassinate,” “slaughterhouse,” and “human meat” with the more palatable “process,” “processing plant,” and “special meat.” Marco, the main protagonist, manages one of the processing plants where humans are slaughtered for meat. Despite the nature of his job, he is critical of the practice. But is it enough to be critical of the practice to make a change—if one cares to make a change at all? (see WLT, July 2024).

Russia

Vladimir Sorokin

Vladimir Sorokin

Day of the Oprichnik

Trans. Jamey Gambrell

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012

In a recent interview, Sorokin was asked how he managed to write such a prophetic book in 2006, and he said, “You only need two dots to draw a line.” In 2028 tsarist Russia is separated from the rest of the world by the “Great Russian Wall.” The restoration of tsarist autocracy brings back xenophobia, trade protectionism, corruption, and nationalism. Oprichniks are the tsar’s elite guards who enforce his rules through terror and repression. The readers follow an oprichnik, Andrei Komiaga, as he goes about his typical busy Monday, fulfilling his daily tasks in the worst possible Russia imagined.

Ukraine

Oleh Shynkarenko

Oleh Shynkarenko

Kaharlyk

Trans. Stephen Komarnyckyj

Kalyna Language Press, 2016

In the year 2114, Ukraine, devastated by a fictional Russian occupation, reverts to a medieval state. The protagonist of this satirical dystopian novel has lost his memory due to a mysterious brain experiment conducted by the occupiers and has to travel to a small Ukrainian town, Kaharlyk, to find his wife, Olga. The story is told through a series of blocks of one hundred words, similar to Facebook posts, that reflect the main character’s disjointed consciousness and trauma caused by war and occupation. Brace yourselves for totalitarian mind control, manipulation of reality through advanced technology, surveillance, disinformation, and other dystopian elements with a tinge of surrealism.

India

Prayaag Akbar

Prayaag Akbar

Leila

Simon & Schuster India, 2017

It’s the 2040s, and India is ruled by the Council, which uses purity and tradition as tools of control. Shalini imagines her daughter Leila, who was supposed to turn nineteen. But Leila was taken away from Shalini sixteen years ago because she is a child of an interfaith marriage. Shalini, who has an elite background, ends up in a Purity camp where she’s forced into submission through labor. Akbar’s debut novel portrays a walled-off community based on the religious segregation of Hindus and Muslims, and it’s just right for those looking for an Indian version of The Handmaid’s Tale. The novel was also adapted into a Netflix series in 2019.

Algeria

Boualem Sansal

Boualem Sansal

2084: The End of the World

Trans. Alison Anderson

Europa Editions, 2017

Abistan is a totalitarian state revolving around a fictitious religious ideology reminiscent of Islam: a deity called Yölah, a prophet Abi, and a sacred book called Gkabul. Remembering the past is prohibited, and an omnipresent surveillance system reports all deviants. The main protagonist of 2084, Ati, meets an archaeologist who discloses that his recent excavation casts doubt on the state’s interpretation of history. Prompted by this meeting, Ati sets out on a journey to discover the truth (see WLT, Jan. 2016; see also Dinah Stillman’s 2012 interview with the author, “A Rustle in History”).

Jamaica

Diana McCaulay

Diana McCaulay

Daylight Come

Peepal Tree Press, 2020

In Daylight Come, it’s the year 2084 (yet again). The fascist Domis rules over a Caribbean island, Bajacu, and disposes of everyone who turns forty. The island doesn’t have enough resources because of climate change, and people work at night to hide from the scorching heat. Sorrel and Bibi—daughter and mother—attempt to escape the oppressive government, hoping to join a group of rebels called Tribals and find an alternative way of living.

Taiwan

Yan Lianke

Yan Lianke

The Day the Sun Died

Trans. Carlos Rojas

Grove Press, 2018

Li Niannian is a fourteen-year-old boy who lives in a small Chinese village with his parents. One night, he notices that all the villagers start “dreamwalking,” and in this mysterious sleeplike state, some act out their deeply repressed desires, leading to havoc, violence, and death. At first, Niannian’s family rejoices (his parents run a funeral parlor), but as society descends into chaos and optimism fades, what will they do? The novel takes place in a twenty-four-hour period and is comprised of hour-by-hour reports. With elements of magical realism and mythlike storytelling, the book explores blind obedience and political conformity.

Argentina

Ricardo Romero

Ricardo Romero

The President's Room

Trans. Charlotte Coombe

Charco Press, 2020

A child narrator and his family live in a respectable neighborhood in a typical house with a president’s room. There’s one in every house, by the way, and it’s kept clean in case the president ever shows up. This allegorical tale shows how an authoritarian state finds its way into the private lives of its citizens in an eerie, Kafkaesque manner. Told in vignettes, sometimes no longer than a paragraph, this book is a quick read that can be consumed in one sitting.

United States

Louise Erdrich

Louise Erdrich

Future Home of the Living God

HarperCollins, 2017

Another novel for the fans of feminist dystopian literature and Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. The evolution has been reversed, and women give birth to a seemingly primitive human species. Because of the evolutionary crisis, the US government becomes more authoritarian and detains pregnant women to save humanity’s future, using religion to justify their actions. Cedar is a pregnant Ojibwe woman who finds her Ojibwe biological family and tries to avoid being captured (see WLT, Nov. 2022).

Egypt

Basma Abdel Aziz

Basma Abdel Aziz

Here Is a Body: A Novel

Trans. Jonathan Wright

Hoopoe, 2021

Homeless boys are brought to a rehabilitation center that turns out to be an army training camp. They attend lectures that indoctrinate them to back up the authoritarian regime, learn to fire guns, and receive corporal punishment for disobedience. The boys are called the Bodies, while the authorities are called the Heads. The main goal is to destroy the oppositional group advocating for an overthrown president’s return. The novel is mainly narrated by Rabie, one of the abducted boys, and depicts the inner mechanics of dehumanization and programming of an oppressive regime (see WLT, Jan. 2022).

University of Oklahoma