Thirty-Six

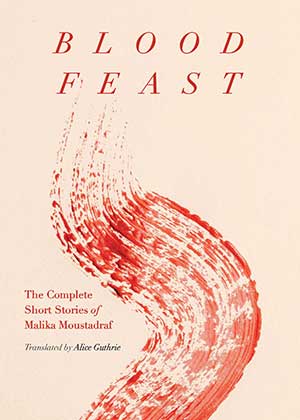

Malika Moustadraf is a feminist icon in contemporary Moroccan literature, celebrated for her stark interrogation of gender and sexuality in North Africa. “Thirty-Six” is one of the stories in Blood Feast, the complete collection of her published short fiction, forthcoming from Feminist Press on February 8, 2022, translated from the Arabic by Alice Guthrie. “Thirty-six” refers to the wing in the regional hospital in Casablanca for those suffering from mental illnesses. The term has since become slang for “crazy” or “difficult.”

I hate Saturdays.

I hate Saturdays.

I know some people hate every day of the week, and they don’t complain. But it’s different for me, or at least I think it is.

Every Saturday morning my father shows up very early, dragging his big feet. His swollen paunch clashes with his scrawny build. His face is long and narrow; his forehead bulges with protruding veins. He’s not remotely handsome. Each Saturday he has some woman with him I’ve never met before: she never seems to resemble the woman from the week before, and she’ll definitely be nothing like the woman next week either. Today he sends me down to Ba Ibrahim’s store. It’s dark in there, and the stink of decay wafting out makes me nauseous. I don’t usually buy our groceries from him. His eyes are crusted and red. He takes a snort of snuff, triggering an endless sneezing fit, then wipes his nose on a grayish handkerchief that looks more like a strip torn off a flour sack, sticky with caked, doughy old snot. He opens the handkerchief, contemplating the contents for a moment, then stuffs it back into his pocket. He tries to muster a few words of welcome, but smiling doesn’t suit him. His long, wonky teeth are algae-colored. I keep my distance from him and utter a single phrase: “Tall Aïcha.” Clamping my arms around my chest, I wait. Our neighbor comes in, her newborn son in her arms. The baby screams insistently and sucks on a bottle of caraway and “woolly cumin” brew. The woman says to Ba Ibrahim, “Take him, the little shit won’t shut up.” He silences her with an angry gesture of his hand. “He’s nothing but an angel,” he says. “I have just the right medicine for him.” I turn my eyes toward the baby to get a closer look at a real angel. His face is lashless, browless, as if he’s suffering from alopecia. He opens his mouth as wide as it will go, screaming violently, his whole face a huge, open mouth, his uvula trembling in his throat like a tiny bell. Ba Ibrahim blows sebsi smoke in the baby’s face once, twice, and then he finally falls quiet. The baby’s eyes roll back in his head, and he falls asleep. The woman reaches inside her top, releasing a sour odor, brings out a few dirham notes, and holds them out to the shopkeeper, who touches them to his forehead before accepting them. The woman’s foul smell must be on the dirhams. The woman thanks him in the kind, gentle way a vinegar-scented woman in her forties would. She leaves, and I repeat my order: “Tall Aïcha.” He heads for the back of the shop. I always used to expect him to hand me a gigantic woman when I placed that order, but instead he’d give me two bottles wrapped in newspaper. In that girly voice of his, completely incongruous with his scary appearance, he says, “Straight home, now.” Then goes back to his usual corner.

Once I was tempted by that blood-red liquid. I downed the dregs of my father’s abandoned glass all in one go. Then I vomited up everything inside me and a revolting smell like rotting socks clung to me for the rest of the day.

* * *

My father closes my bedroom door. He’s given me half a round flatbread with some canned fish in it. As soon as he’s gone I throw it out the window. I won’t lock the door, but don’t try to come out. From the other room comes the scent of grilling meat; my mouth starts watering. I push the door ajar. Lascivious laughter, rude words, that delicious scent creeping into my nose. My guts go into a frenzy, and it’s getting hard to keep my rumbling stomach quiet. I swallow my spit with difficulty, fingering the few dirhams in my pajama pocket. Tomorrow I’ll buy half a kofta and onion sandwich. Laarbi always looks gross, his big, wobbly belly hanging over his food cart, his fingers up his nose. After he’s done digging around for boogers he goes right back to flipping the pieces of kofta and sausage. But it doesn’t matter, his food is delicious, and maybe the filth adds to the flavor. He has even more customers crowding around his stall than flies landing on his chopped onion and tomato.

* * *

“Dad, I wanna watch television. I wanna see Sinbad. I can’t sleep.” My grandmother tells my father that cartoons show real-life creatures that live somewhere or other, just like we do. She picks up her prayer beads and goes back to running them through her fingers and softly repeating prayers. The fingers of her other hand don’t leave her nostril and don’t cease their hopeless attempts to pluck some tiny hairs. Sinbad travels the world on his ship. The djinn comes out of the depths of the sea. The ship capsizes and I fall out of bed. The bedroom is dark. The coat hanger turns into a djinn with outstretched arms coming toward me. I hide my head under the covers. I listen to my heart beating like it’s right inside my ear. Where is my mother? I don’t see any pictures of her on the walls. There’s just a picture of a big monkey wrapping toilet paper around his huge, hairy body, his jaw hanging open idiotically to reveal rusty teeth the size of fava beans. Why does my father insist on hanging that picture in the middle of the hallway? Who was it that said human beings are descended from apes? What does my mother look like? Do I have some of her features? Is she fat? Is she white? I used to carry a notebook around and try to imagine her. I would always draw a woman with no face. One day, on a visit to my grandmother’s place in the desert, she said to me, “Your eyes are like your mother’s.” I was happy: finally, I knew what my mother’s eyes were like. Then, picking a louse out of my hair, she added, “Yes—your eyes are completely shameless. As the saying goes, ‘Throw a handful of salt in her eyes and she won’t even blink.’” My heart was pounding as I wriggled out from between my grandmother’s knees. I hated her, and I loved my mother now more than ever.

* * *

This Saturday night I feel a searing pain rip through my belly. Something warm is pouring out from between my thighs and running down my legs. It smells foul. I understand, but I don’t know what to do. I put my hand between my legs to stop this disgusting contamination from flowing. My fingers are covered in blood. A droplet falls, dark as liver. I shudder, the iron bed frame creaks. My teeth chatter. I feel degraded, humiliated, I’m cringing in abject shame. What if the blood floods the whole room? The stairs? The neighborhood? I cry out. My father comes. His eyes are half-closed. “What’s the matter?” His voice sounds like a death rattle. “What’s the matter?” His eyes are half-open. “What’s the matter?” His face is long and his forehead bulges more than ever. Little curly hairs he wishes would conceal his bald patch. “What’s the matter?” His voice gets sharper. Tears like grains of sand, like needles piercing my eyes. “What’s the matter?” I want my mom. He pulls off the bedcover, he can see my private parts. My sheets are sopping with blood. My hand is between my thighs. I’m still trying to stop this disgraceful bleeding. It continues. He looks down and his eyes are shards of glass, taking in the scandal-soiled sheets. He looks at my breasts, at the red zits that cover my face. His Adam’s apple going up and down while he scratches the back of his neck; I shake my head from left to right as if defending myself from an accusation. He opens the closet and pulls out an old foot towel. He holds it out for a moment, then chucks it at me, hard. He spits on the floor and leaves the room. I’m still cowering in a ball on the bed. I look at the bloodstain, at the scratchy towel. Here comes the woman who does all that shameless stuff with my father: now she’s coming right into my room! She’s concealing her nakedness with a white cloth wrap. She laughs a gelatinous, brazen, and mirthless laugh. Then in her smoker’s rasp she says, “Come on, best get on with it, you’re a woman now.” That day I hated my father, I hated my body, and I loved my mother.

That day I hated my father, I hated my body, and I loved my mother.

The next morning I am woken by the sound of that woman my father brought to the house: she’s shouting. I open my puffy eyes and then the door, just a crack. The woman is throwing green banknotes in my father’s face, frothing at the mouth, the arteries in her neck bulging. She looks like a frog. “Is that how cheap you think this is?” she yells, gesticulating crudely at the area below her paunch. My father’s baggy pants are so low-slung they show half his backside as he rams the notes back into his pocket. He raises his leg to kick her in the butt. “Get out, whore! Women keep the fires of hell burning bright!” The woman dodges the kick and flees. He slams the door behind her with blatant violence.

She keeps on shouting even once she’s out in the street: “Haram on you, taking advantage of a hard-working woman—God curse the money you save by cheating me of my dignity, that’s a sin!” His eyes are as narrow and tight as two dark little pinpricks, out of proportion with his huge, densely pockmarked nose. He leans his forehead against the wall. I can sense his rage from the rhythm of his breathing. He punches the wall, spits on the floor, I hear him cursing womenkind and everything they stand for. The woman is still yelling: she wants her djellaba and her handbag back. He opens her handbag and throws it out the window. Its contents scatter across the asphalt. The children race to steal whatever they can get their hands on as he rips up the djellaba and throws that out the window too. He sits down on the edge of a chair, panting, then laughs in relief.

Every Saturday it’s basically the same story on loop.

I can guess what will happen next: he’ll go into the bathroom, wash, then he’ll turn toward Mecca and say, “I prostrate myself with holy intention, offering an extra prayer to Allah.” Every Saturday it’s basically the same story on loop. Only a few minor details change from week to week.

Whenever Saturday is getting near, an enormous, heavy stone bears down onto my chest and doesn’t budge. I have come to hate Saturdays and to understand why the neighbors call my father “Thirty-six.”

Translation from the Arabic