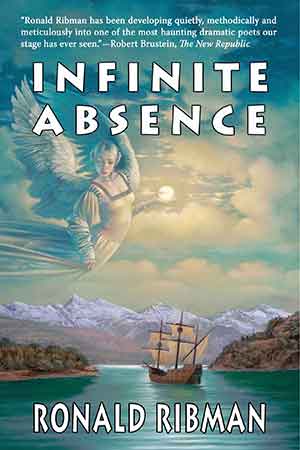

Infinite Absence (an excerpt)

About the Novel

This is a story of dispossession and a man who wrestled with God: sometimes dispossession as in simply being thrown out on the street in Lower Manhattan, or in Punta Arenas, or Anywhere, stripped of our stuff, and left to survive whatever comes our way.

Or sometimes dispossession that rises to primal myth, being thrown out of the Garden of Eden, stripped of our immortality, and booted from the sight of God. Whichever way, or in whichever thousand other forms this story embeds itself into our psyche, it is always a story of eviction, loss, and separation. And we are always that creature, forever abandoned in a created universe of unimaginable expanse and consequence, yet somehow mysteriously webbed into the laws of that universe. And whether we choose to worship its Creator, curse Him, deny Him, or even try to imagine hunting Him down as a whale, we are still forever inextricably entangled with Him—a God who has chosen to be infinitely absent from us!

In Infinite Absence, that God, within whose universe we are so inextricably entangled, comes to call on Peabody, one bright winter’s day in a mausoleum.

Prologue

Prologue

Except for a band of grave-desecrating hoodlums who came one night to drink, knock over tombstones, paint swastikas, and ultimately be sent fleeing for their lives, the burial vault of Hector Helmontos, set as it was upon a gently sloping knoll in the grandest place of privilege above the surrounding necropolis, might have gone undisturbed for a hundred or a thousand years.

But hearing the sounds of life from within its earthen pot, from beyond its honored place atop its marble pedestal, the severed head of Hector Helmontos, floating in a golden sea of honey, drenched through to every pore and channel, began to sing to them!

Clotheshorse

1

I’ve taken to dressing to the nines. It’s an affectation I picked up in Rome some years back in the summer of 1932, and it suits me. In these gray depressive days excruciatingly prolonged by Mr. Roosevelt’s economic policies, I’m a burst of color and panache, striding about Manhattan in my blown-open cashmere overcoat, my tailored suit, my matching scarf and yellow silk breast-pocket handkerchief. My hat for the day is the Borsalino with the inch-and-a-quarter Grosgrain band. Not my absolute favorite, but a favorite. My absolute favorite these days is my high-crowned James Cagney-style felt fedora done in charcoal gray.

I’m the Peabody in Peabody Industries. When you talk about Peabody Industries, you’re talking about me. There is no other Peabody. I’m the last of the species, tracing my lineage back to my grandfather’s grandfather who began the business operating out of the old foreign concessions of Canton, China around the turn of the 19th century. Our family was in the China Trade. We dealt in silver and tea, Chinoiserie and silk, and when the Emperor of China decided he didn’t like anything my grandfather’s grandfather had to sell, we sold him opium—which the heathen Chinee came to like a great deal. We bought the stuff sometimes from the British in India—when we could get them to sell it to us—but mostly from the Turks, who were always eager for a good deal from the Americans. It was the best of times for getting rich and we got rich, what with the Royal Navy ruling the seas and its cannons prepared to reduce the Emperor’s cities to rubble over any insult to cargo or flag. When my grandfather’s grandfather came to Canton, the Emperor of China thought his Celestial Kingdom ruled the world; when we left, he knew it was Queen Victoria. The China Trade made the best American families rich, and out of opium we built the infrastructure of the United States: the mines, the railroads, the factories, and the great universities of Harvard and Yale and Princeton.

We’re just a few weeks into 1937—our first board of directors meeting of the new year—and practically every member of the board is panicked, seizing the opportunity of Roosevelt’s second inauguration to make dire forecasts about the current economy and the baleful direction of foreign events. They think the president a charlatan, a dangerous socialist, a betrayer of his class, pied-piping the country to economic ruin. And there’s not one statistic in all their rattling documents to disprove it. After four years of Mr. Roosevelt’s fireside chats and rousing speechmaking, everything’s as bad as it was when he took office. Just lots of make-work jobs that produce no lasting employment or real economic wealth. Consumption of consumer goods shows no sign of rising. Unemployment stubbornly refuses to go down. Production remains as stagnant as ever. On the streets there’s not one less begging hand held out; not one less apple stuck under your nose. As for overseas markets, unmistakable black clouds lour on everybody’s horizon. Herr Hitler shakes his fist in Europe. Mussolini never shuts his mouth. And in the Orient, where we have enormous business interests, the Japanese continue their plunder of China, heedless of the League of Nations’ fulminations and the general outrage of the world.

Herr Hitler shakes his fist in Europe. Mussolini never shuts his mouth.

Listening to these gloomy prognostications, I’m idly reminded of Rudyard Kipling’s admonition that if you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs, the world’s your oyster—or something to that effect. I’m not sure I’ve accurately quoted the words. I pride myself in never remembering Kipling too exactly. He’s a second-rate poet, and quoting a second-rate anything too exactly is always a trifle demeaning. Nevertheless, the memory of his words impels me to hold my tongue, if only to allow this morning’s corporate drama to build. I feel as if I’ve been set down into a diorama or theatrical piece that has been staged many times before and will be staged many times again. Sometimes I appear as the boy being shown about the business by his father, sometimes the young man fresh out of college, learning the ropes. Today, I make my appearance at the head of the table: chief executive officer and chairman of the board. And when orderly conversation has broken down and everyone is merely exchanging heated words with his neighbor—the pall of tobacco smoke infecting every fiber of clothing—I take my cue and tap my pencil against my water glass.

“Gentlemen, I couldn’t agree with you more concerning Mr. Roosevelt. He is certainly everything you say about him and, undoubtedly, some things only decent manners restrain me from saying. But, I beg you to remember, Peabody Industries has prospered in one form or another for well over a hundred and twenty-five years, and that with any luck at all shall manage to survive what can only be Mr. Roosevelt’s final four years as president.

“I should also like to remind you that, since you saw fit in your good judgment to make my brother, Hector, our man in South America, he has done nothing short of accomplishing miracles, bringing us the greatest increases in year-over-year profits these past five years, while at the same time building the most secure economic alliances with those in power. There is also hardly any need to remind anyone of the continuing accomplishments of our man in the Orient, Cyrus Cunningham. Thanks to his untiring efforts, I believe Peabody Industries has little to fear from any expansion of the Japanese Co-Prosperity Sphere. Our place as a reliable and trusted partner to Japanese industry is unquestioned.

“As to the situation in Europe and Herr Hitler, I believe him to be a reasonable man only seeking to redress some of the imbalances brought about by the harsh terms of the Versailles treaty. Once these adjustments have been made, I have it on the highest authority of our friends in German industry that we may look forward to an even more profitable future, and that the German government shall not forget those who stood by her in her economic difficulties . . .”

I continue on in this fashion for some time, finding real pleasure in holding the attention of my board. Not an eye that is not upon me, and often as I speak I can see some of them scribbling notes to themselves upon their yellow pads, or sliding them over to their neighbors for perusal. Although I have made notes of my own on my yellow pad for when I speak, once I get past my notes I know I will be able to go on in a most expansive and easy manner. It’s a gift, and it delights me beyond measure. Truthfully, it almost doesn’t matter to me what I say, as long as I can speak the speech and hear the words and witness the sheer pleasure of my own thoughts carried on my voice. Lighting my cigarette, standing up from my chair and strolling about the room, resting my hand in passing on every man’s shoulder, I speak about Joseph Stalin and Communism, I speak about the prospects of doing business with the Soviets and the excellent series of articles published some years prior in The New York Times by Walter Duranty, praising the collectivizing of the Ukrainian farms. I feel like Henry V rallying the troops at Agincourt.

After they all depart, taking their briefcases and note pads with them, I notice a single pad sprawled on the conference table as if haphazardly tossed, not particularly near any man’s chair, not particularly seeming any man’s property. And printed on its lined and yellow face, in the large block letters of a schoolboy, the single penciled word: ASSHOLE.

2

It’s useless trying to figure out who among them has done this. I’ve tried in the past with other slights and it was never successful. Now, I merely leave it where it lies—and who’s to say for whom it was intended?

In my office it’s a double hit from my brother: a letter from him concealed in a stack of trivial correspondence, and, seated directly in front of my desk, waiting for God knows how long, a female official from his veterans foundation. It’s been almost five years since Peabody Industries took over the responsibility for the Foundation, placing it within the aegis of our corporation and funding its activities as the price for bringing Hector aboard our South American operations. The arrangement has all been my doing, though you might think by the deference I accord my board of directors it was their idea. Not in the least! It was also my decision many years before that to send Cyrus Cunningham to head up our Far East operations. That, too, worked out brilliantly, though in that instance, too, it earned me little credit from my board of directors and cost me the one man I always considered my friend. What can I say? Lacking any particular talent of my own, it’s my genius to recognize it in others. And that is the second of God’s three gifts to me.

The lady before me is in her sixties: no nonsense, no lipstick, her gray hair done up under her hat. I vaguely remember meeting her before, having a drawn-out conversation with her from which there was no escape. But she is unimportant to me, and even when she introduces herself again her name passes by me, making no imprint whatsoever. She has come to thank me for turning over the deed to our family house on West 54th Street to the Foundation for its permanent headquarters. I haven’t the slightest idea what she’s talking about. I’m constantly set to signing papers. All day they are plunked down on my desk for my signature, and I sign them with barely a glance. But I’m sure I’ve signed over no such deed to the house. In any event, the house belongs to Hector. I gave it over to him many years ago, and he may do with it as he pleases. She evidently confuses him with me, what he has done with what I have not done. But I take the gratitude she is pouring out so effusively and do not in the least disabuse her of her mistake. It makes no difference. She will never discover it, or if she does she will think she has misunderstood or misheard. It will never come back to embarrass me, or haunt me, or punish me. I’m never punished for what I do. Once when I was five, I willfully smashed all of Hector’s dearly beloved toys to pieces against the wall, and the only thing that happened to me was that I was taken out for ice cream. And that is the third of God’s three gifts to me!

I’m never punished for what I do.

“Did you ever run into your brother, Hector, while you were both serving in France during the war, Mr. Peabody?”

“I’m sorry?”

I pretend I’m momentarily distracted and haven’t heard her question. I don’t know what she’s talking about. I never served in the military. I never wore a uniform, not even in private school. I can’t even conceive where she could have gotten that idea. During the war I was given an exemption from military service. I couldn’t serve. The draft board said I was too valuable heading up Peabody Industries’ war effort to be inducted. Maybe I told her I had been in France. I might have said something to that effect. I have summered a number of times in Viareggio and Nice and elsewhere along the French Riviera. I might have said something like that.

“I believe you said you served in France during the war, and I was just wondering if you and your brother ever ran into each other while you were there?”

“No, not really. We were in different outfits.”

“Maybe you might have met my son, Lieutenant Alvin Forster? First Lieutenant Alvin Forster? He served with the 3rd Division at the Marne.”

“No, I don’t believe so.”

“He was killed at Château-Thierry.”

Of course, he was! And how am I supposed to greet this particular piece of news? Her son was killed twenty years ago, and she’s still talking about it? A million men killed each other, and she actually thinks I might have run into her son? No wonder she works for the Foundation. She’s perfect for the job. Or maybe she’s not here at all to thank me for donating Hector’s house to them, but just trying to trap me, because her son was killed at Château-Thierry and she really doesn’t believe I fought in the war at all. But no. There’s never any trapping me. It’s all only an honest outpouring of the heart, a mother’s grief that will not abate.

“I can’t tell you how much I admire you and your brother for all that you’ve done for our veterans. So many people don’t realize how great the need continues to be, especially in these times. Your stopping by the Foundation last month to visit with us was an inspiration to us all. And now this gift of the house so that the Foundation might have a permanent home. I don’t know what to say. I . . .”

I’m just delighted when, after some more of this, this elderly lady with her severe, no-lipstick, no-nonsense face—now tearing up in uncontrollable gratitude over a house I have not given away—allows me to put my arm about her shoulders and escort her out of my office. She’s quite made a mistake concerning me, but, as usual, my brother’s everlasting kindness spreads its penumbra over me. To stand in his shadow is to stand, as always, out of the deserved and frizzling blister of the sun.

3

The letter from him is weeks old. It’s made its way up to me from Argentina. Though he fills me in on company activities there, it’s only the briefest sketch, saving, no doubt, more precise and detailed business news for those members of the board he deems more needful receiving it. For me, it’s only needful to know that while he was in Chile he ventured down to Punta Arenas and saw the house he once lived in, visited the graves of his birth parents, and walked along the Straits of Magellan, skipping stones and plunging his hands into the cold water, remembering . . .

Dallas, Texas

Editorial note: Dr. Ribman’s obituary appeared in the New York Times on July 4, 2025.