Balls and Stars (an excerpt)

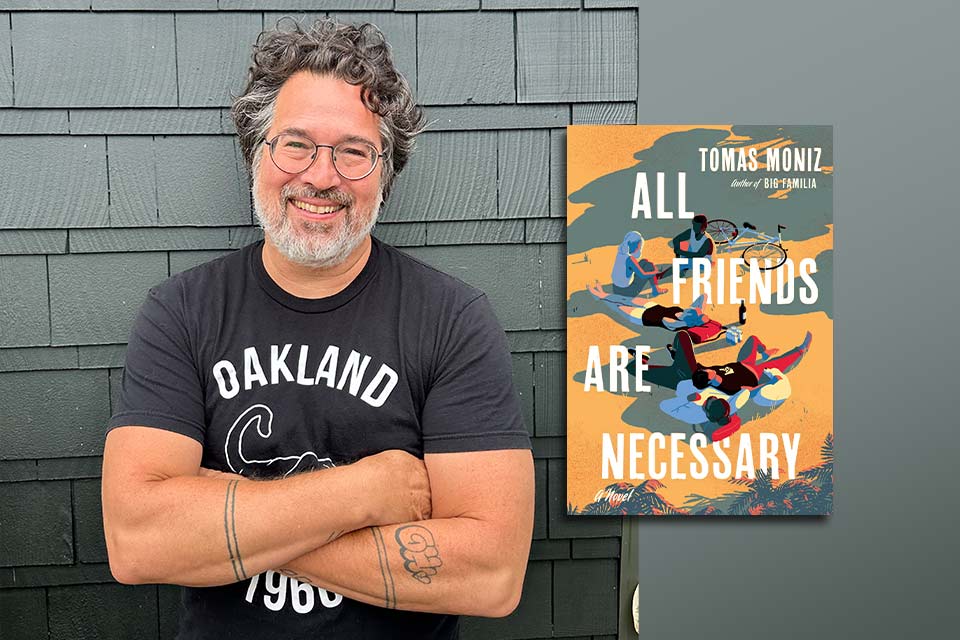

On June 11, 2024, Algonquin published Tomas Moniz’s second novel, All Friends Are Necessary. Set during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic in Oakland, California, the novel is an anthem to both queer and platonic love and the joy of giving yourself up to the essential force of community.

I started taking long strolls around my neighborhood, always aimless, just walking away from my place on Thirty-fifth and Paxton. Pre-pandemic, I never walked anywhere if I didn’t have to. I loved my beat-up truck and would even drive the half mile to the Mexican markets that dotted Fruitvale Ave between MacArthur and International.

The markets usually had everything in stock, while the larger grocery chains were uniformly pillaged by the Oakland Hills residents who were too concerned about their health to come to the crowded and impossible-to-social-distance-in shops throughout East Oakland.

But lately, walking felt glorious, something to dress for, to take a look in the mirror for, to primp and pose. My hair was puffy and as full as it had ever been in my life.

Lately, walking felt glorious, something to dress for, to take a look in the mirror for, to primp and pose.

I explored side streets and neighborhood parks. I appreciated the city-sponsored Slow Streets, which were off-limits to cars. Every time I discovered one, I saw kids biking and playing, elders walking leisurely. People even set up chairs to sit outside and safely gather with neighbors.

I’d always stop at Foothill and Fruitvale to buy sliced mango covered in tajín and lime, from a masked young man with a fruit cart. I’d get street tacos on Twenty-sixth Avenue, a side street off of Fruitvale, where Oakland PD always hassled the vendors about fire safety. I’d relax in Josie de la Cruz Park, with its miniature soccer field.

One evening, I sat in the grass and listened to this group of kids talking shit in Spanish. They had ripped down the do-not-enter caution tape meant to prevent people from gathering on playgrounds and sports fields. They had reclaimed this public space, unmasked, living out a physical closeness I didn’t have but painfully craved.

I eyed this one kid as he picked up a soda can and threw it at a dog, missing him by inches. It was awful. And I stared in disbelief, because I was sure it was the same dog I’d freed the night before the lockdown. His name came right back to me: Brucebruce. The last time we’d encountered each other, he had raced through traffic on Foothill.

The dog very casually sauntered out of range and sat waiting the teenagers out. I left the park thinking, Good for him. I was glad the dog had survived—he was making this work, like all of us. I even felt a little responsible for it.

The next time Metal Matt and I hung out, I told him the story of how I had liberated this dog called Brucebruce from its abusive owner right as the pandemic started, thinking he’d be impressed by my act of kindness.

But he was aghast. Like, how could I just let some animal run wild on the busy streets of East Oakland and think, in any way, that what I’d done was a good thing?

He shook his head and pulled Sabbath toward himself, cooing: I’ll always protect you, Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, especially from Evil Efren.

You know that’s a dumb nickname.

It’s the title of Black Sabbath’s fifth album, arguably their best. How’s that dumb?

It was still dumb, but he was right about Brucebruce. How arrogant was I to free an animal and yet to take no responsibility for its safety? Despite my best intentions, I might have put the dog in even more danger out on its own.

I frowned, self-loathing surging through my body, as I thought about how often my actions were selfish.

I wasn’t brave enough to call my father back when he asked me to. As I’d witnessed Luna cradling our child’s body—the nurses and the doula reverent and ceremonial—I’d refused to hold or even look at the baby.

* * *

That very night the kittens showed up at my door.

I stepped out into my backyard at 3 a.m. because something kept yowling and whining. I opened the door ready to shoo the thing away, and two baby cats, one orange and one gray, pranced inside like they lived there and were returning home from a joyous night out.

At first I was aggravated, like Get out of my space, but the orange one rolled over, and I could see his cute little balls, soft and furry, in an adorable oval shape. The gray one raced up and swatted the other kitten feebly. I fed them some chicken I had left over from my favorite spot: Lucky Three Seven. They have the best wings, covered in this sauce called G Fire, which I know must have way too much sugar in it. But, anyway, I should’ve known the kittens would be like, Hell yeah, we gonna live here. They snuggled up at the foot of my bed and slept like they were the safest little forest creatures in the world.

After a couple weeks of giving them human food, I broke down and bought canned cat food and kitty litter and made an appointment at the outdoor free vet clinic. But when the vet tech asked their names, I realized I never considered them mine, because who names a cat Ratty and Balls. I’d named them that to make fun of them, not to love them.

Ratty and Balls, the vet tech said. Like he was clarifying the names.

He was dressed head to foot in PPE attire, so I only saw his eyes.

Yes, I enunciated through my mask.

Okay then, but Balls better enjoy his for the next hour—he’s about to have them in name only.

His balls were the soft yellow of unripe apricots. I felt a pang of regret. Not that I’d named him Balls, but that I’d brought him here to lose them.

It had been a hard year. I felt the need to hold on to such tiny precious things.

It had been a hard year. I felt the need to hold on to such tiny precious things.

I bragged to Metal Matt at Peralta Park that I was making amends for releasing Brucebruce by fostering these two feral kittens, but I complained how they never really let me pick them up and spent most of their time racing through my apartment chasing crumpled-up Post-it notes.

Metal Matt said, You mean the cats play fetch?

They don’t fetch. They’re cats, not dogs, I said.

Do you throw these crumpled Post-it notes?

Yes.

And do the cats bring them back to you?

Yes.

You have cats that play fetch. Do you let them outside?

At night, when I go out. They follow me, but then they always come back inside.

When I told Terrance over Zoom about the cats, he said, Ah, you’re one of those people who got quarantine pets. I read an article about it. It’s apparently a thing that lonely people do.

I’m not lonely.

Do you have a quarantine pet?

No. I have a consensual relationship with two abandoned cats that have adopted me.

They must’ve known.

Known what?

Known that you’re lonely. And that’s okay. We all are, really.

* * *

One night in December, I stepped into the backyard to witness the planetary convergence that everyone was posting about. I had a cup of tea. I let Balls and Ratty out, watched them sprint away into the darkness. I heard the side gate bang open and closed, and was about to shout Get out when my upstairs neighbors, a young couple—Jas and Jan—walked into the yard and waved at me. I waved back like this was a regular occurrence, but I don’t think I’d ever seen them back here. Normally, I saw only one of them or the other when they stepped out their front door to pick up the nonstop deliveries that arrived: takeout, groceries, Amazon boxes.

They searched the sky.

You know the stars are lining up tonight, Jas said, as if I’d asked him to explain his presence. He sounded strangely excited, like this was something he’d been waiting for.

You know the stars are lining up tonight, Jas said, as if I’d asked him to explain his presence.

Not stars, babe. Planets, Jan said.

Yes, that’s right—planets. Saturn and Mars.

Jupiter, not Mars. Babe, come on, are you just teasing me? she said, and she reached out to push him.

I realized he might have been teasing her. They were cute together.

My cats sauntered up to me and sat at my feet like I’d trained them.

Oh, my god. Look, Jas. It’s our cats. It’s Kurt and Cobain. Where have you two been? We looked all over for you.

She hustled over and picked up Ratty, who meowed like she was so sad and scared.

Balls meowed like he wanted to be picked up. Like I hadn’t tried to pick him up every day for weeks.

Jas picked up Balls and cradled him like a little newborn baby, his four little paws reaching skyward.

Jan, all tears and excitement, asked, Have they been with you the whole time?

I said, I thought they were feral.

Jan looked at Jas and said, I told you we should have put up flyers. I knew they were around here.

They raced toward their apartment, forgetting all about the planets and stars.

The cats looked back at me, and just like that, they were gone.

I thought about saying something about their medical records, but, really, what could I say?

I figured Jas would soon find the balls gone and figure it out.

I remained outside and threw the rest of my Post-it notes into the darkness. Every time I threw one, the floodlights went on.

When I was finally out of Post-its, I just sat there listening to the sounds of East Oakland: the tire squeals, BART screeching, a car alarm, the ever-present and year-round pop of fireworks.

I looked up into the sky, and, sure enough, I saw the planets converge. It was a beautiful sight, that bright, steady light that for centuries had guided people home.

Oakland, California