The Protest Art of Walid Ebeid: Reflections on Four Paintings

The artist is a lawyer who defends any accused person when society plays the role of the judge. I am generally biased for injustice and those stripped of their rights.

―Walid Ebeid

Reflecting on the work of Egyptian artist Walid Ebeid, Yahia Lababidi considers the “artist as witness, activist, public scold, and collective conscience, all rolled into one.”

Born in Cairo, Egypt, in 1970, Walid Ebeid spent his early childhood in Yemen. The precocious artist recalls, fondly, connecting with nature and using oil paints at an age when other children were still using crayons or markers—with the encouragement of his father, who supported his art. As a young man, Ebeid was raised to respect women, whom he was surrounded by, and describes it as a rude awakening when he grew up to see how badly women were treated by society, outside his loving family environment.

Back home in Egypt, the prolific artist wasted no time in establishing himself. Shortly after graduating from art school, fortuitously, Ebeid secured the support of Farouk Hosny, the minister of culture at the time. Hosny, an artist himself, immediately spotted Ebeid’s talent and helped the promising young artist arrange his first solo exhibit, People You May Know (a career-establishing event that might have taken a recent graduate nearly a decade to achieve on their own).

Ebeid continued to actively take part in the local arts scene, going on to exhibit internationally. His primary artistic influences, as he was developing his style, were Gustav Klimt and ancient Egyptian art. It was a happy coincidence and source of pride for Ebeid when he discovered that his Austrian hero, Klimt, was also influenced by ancient Egyptian art, so that Ebeid felt he had come full circle: distilling inspiration of his rich heritage through the filter of a European master.

A self-described “risk-taker,” Ebeid found his artistic calling as a voice of the people or, more specifically, an advocate for the downtrodden. Not one to shy away from controversial subjects, even dark and disturbing realities, he went on to explore taboo issues in his work, such as domestic abuse, forced marriages and child brides, government torture, the Egyptian revolution and its miscarriages, immigration, poverty, hunger . . . Ebeid’s figurative art, which he describes as “realistic-expressionism,” is often dramatic, symbolic, accusatory. His confrontational work demands an emotional response from the viewer, as if to say: Look at our suffering, the one you’re complicit in. If we choose to defy your double standards, don’t you dare condemn us.

Like his formative influence, Klimt, the female body is central to Ebeid’s art.

Like his formative influence, Klimt, the female body is central to Ebeid’s art, as muse and allegory but also as site of protest and battleground. Aware of his power, both as an artist and a male in a patriarchal society, Ebeid seeks to redress an imbalance by sharing his platform with society’s scapegoat: women. Blamed for men’s desires and frustrations, the artist recognizes the paradoxical role women occupy in his embattled culture: at once humiliated underdogs and revered life-givers. The women in Ebeid’s art tend to fall into one of two categories, either defeated and demeaned at the hands of weak and vicious men or unabashedly sensual, goddesses, luxuriating in their skin and bluntly erotic. “Definitely a male gaze happening here,” balked an American acquaintance of mine, on social media, when I shared his art online. Well, Ebeid is a male, gazing adoringly at women, reveling in themselves. What might appear louche, scandalous, or sexist to some could have more to do with the viewer than the artist who only seeks to hold up a mirror to society and his complicated subjects.

Allowed Meat is a complex painting by Ebeid that has it both ways. The scantily clad, barefoot heroine poses seductively in an unglamorous surrounding, a butcher shop, flanked by animal carcasses. Her ashen skin is rendered as unsentimentally as the animal flesh around her, à la Lucian Freud by way of Francis Bacon. Is the dress on the coat hanger a metaphor for the fiery redhead, dangling on a hook, offering her wares? Is that a come-hither look she wears, or is she lost in reverie or regret? Is the voluptuous female seated on the cutting block availing herself to be ravaged, consensually, by a lover or resigned awaiting a customer? What is allowed in this meat shop: only raw carnal desire? What about Love? Is this a portrait of empowerment, defilement, or both?

While Ebeid does not identify as a feminist—calling himself a “humanist” instead—of course, one need not be a feminist in order to recognize gender equality as a basic human right, critical for the health of any society. Yet even a cursory glance at Ebeid’s body of work reveals to what extent he is a champion of women’s issues/rights, intimately identifying with their plight while seeking to amplify their voices and celebrate them. In one interview, he puts it this way: “I myself cannot fathom the reason I hold all this empathy towards women—as if women were the reason for me being an artist.”

Yet despite being a sensitive soul and soft-spoken, in an Arabic language interview he gave on an Egyptian TV show, Ebeid knows what he’s doing and is unafraid to contradict expectations. When his admiring female interlocutor assures him that no offense should be taken by his compassionate work, since he intends no harm, Ebeid differs, politely, but firmly. “My paintings are meant to hurt,” he corrects her. “Really?” she stammers. Yes, he confirms; they hurt those who have done wrong, whom the paintings are accusing.

This is the artist as witness, activist, public scold, and collective conscience, all rolled into one. In this sense, Ebeid’s manner of painting, which can veer into a sort of hallucinatory realism, as well as his concerns, echo those of another Arab artist, Kuwaiti-Syrian Shurooq Amin, a self-confessed “creative thorn in their sides.” Like Ebeid, Amin is a natural-born provocateur and fearless in addressing sexual politics through her arresting canvases, which typically mirror sociopolitical ills and hypocrisies, focusing on female oppression.

Unlike Amin, however, Ebeid’s work has not been labeled “pornographic” and “anti-Islamic” but instead warmly embraced. In fact, Ebeid enjoys a largely female following, and when I posted some of his paintings on Facebook, two Egyptian friends, both women and academics, let me know they admired his work (one gushing: “He’s my favorite for years, now”) and that his exhibits were well attended back home. What’s more, women often reach out to Ebeid and recommend topics for him to tackle. To render their stories faithfully, the artist listens, attentively, so that in his words he can “paint not just their bodies but also their souls.”

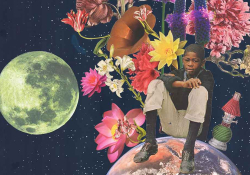

His painting The Immigrant is a kind of shock art, intended to shake us out of complacency.

Addressing one of the great moral issues of our time, the refugee crisis in which tens of thousands of unfortunate souls drowned in the Mediterranean, Ebeid commented: “People who feel like strangers in their own countries seeking for a better life in other places where they will realize that they are more strange.” His painting The Immigrant is a kind of shock art, intended to shake us out of complacency. Reversing roles, and expectations, it depicts a fully clothed man (washed up onshore?) lying next to a naked woman at the beach. He is lifeless and discolored, she pale and languid. One of the nudist’s legs is raised, idly—like a cat’s tail twitching on a lazy summer day. It appears that the woman is reading a book, but upon closer inspection, it turns out to be a passport. This is angry, indignant art, laced with defiance and a strange eroticism. But the true obscenity that such a challenging painting suggests is indifference to the pain of Others.

By association, I think of the sardonic lyrics of a song by English musical artist Morrissey titled “Lazy Sunbathers.” There are not enough words or paintings to address the magnitude of this ongoing immigration catastrophe, but for those who wish to explore it further, I highly recommend a powerful poem by Sherman Alexie, “Autopsy,” which opens with these damning words:

Last night, I dreamed that my passport bled.

I dreamed that my passport was a tombstone

For our United States, recently dead.

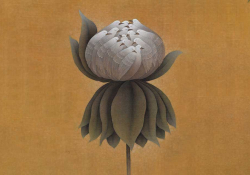

The opposite of freedom features prominently in the parable-paintings of Ebeid, in the form of blindfolds, bars, handcuffs, chains, and, generally, circumstances that bind. A student of Egypt’s illustrious history, one of his works is titled Nefertari, Once Again. Ebeid’s rendering of the great Egyptian queen is a far cry from her typically lavish depiction. This modern Nefertari has fallen on hard times, sitting uneasily on the edge of a sofa, in squalid surroundings. Her royal staff, like her, is diminished and rests like a futile child’s toy on the worn cushions next to her. To underscore her appalling condition, there is a ball and chain fixed to her left ankle. The fallen monarch stares directly at the viewer, reproachfully. What have you learned from our past, she might ask. Where is our ancient wisdom?

Ebeid passionately believes in the edifying capacity of art and its inherent morality, going so far as to say (somewhat provocatively), “If people understood art, God would not have needed to send down religions. Since art teaches us to see beauty in everything and how to love one another.”

Judging by the harsh verdict found in his canvases and the tumultuous affairs of our world, as a species, we have not understood very much of art and religion. So, we turn to his paintings to see our naked, sometimes ugly reflections, in hopes that we remember who we can become.

Egyptians are a funny lot. They’re tolerant, until they’re not. When I recently discovered the bold work of Ebeid, I admit, I was concerned for his safety. I feared an example might be made of him the way it was of another Egyptian artist, Ahmed Naji, whose byline now reads: writer, journalist, art critic, and criminal. After an Egyptian man claimed that an excerpt from Naji’s second novel, Using Life, had made his blood pressure spike and given him a mild heart attack, the young novelist was accused of “offending public morals and promoting obscenity.” This might be faintly amusing had it not ended terribly for Naji, setting a precedent for being the first author in modern Egypt imprisoned for a work of literature.

In the harrowing account of his experience behind bars, translated in The Believer (February, 2021), the unfortunate writer makes this poignant realization:

The regime’s guards fed on humiliation. If their eyes fell upon you for some reason and they took a dislike to a movement you made or the way you looked, they could make an example of you in front of everyone, and when that happened, you had to submit, because any hint of resistance was a provocation. Your resistance signaled there was something inside you that wasn’t broken yet, and their job was to break it.

There are three red lines, he emphasized, that an artist cannot cross in Egypt.

The chastened novelist revisited this heartrending territory in a videotaped presentation that Naji delivered at Apexart, NYC: “Rotten Evidence: Reading and Writing in Prison.” There are three red lines, he emphasized, that an artist cannot cross in Egypt today: frank depictions of sex, mocking national identity or mythology, and questioning religion.

Yet despite flirting with those three prohibited red lines, Ebeid has mercifully escaped becoming another cautionary tale while continuing to offer provocative resistance through his art. A decade and a half older than Naji, Ebeid knows all too well about the brokenness that Naji alludes to in what can, sometimes, seem like a country-wide prison. But instead of being cowed, Ebeid throws the crushed spirits he rescues in paint right back in the face of their oppressors. This lamentable lot might be unfree in their homes and workplace, the painter suggests, but the jailer is never free. That’s the greater spiritual truth that I believe emboldens Ebeid and his gallery of wounded souls. As Arab American poet-activist Suheir Hammad puts it: “Do not fear what has blown up. If you must, fear the unexploded.”

An unsettling example of one systematically broken and barely unexploded is Ebeid’s Settled Citizen. If the vacant, extinguished look in the eyes of this citizen were not enough to betray his condition, his bomb-site of an office hints at a lifetime of disappointments that surround him like shrapnel. While his teacup and water bottle sit upright as he does, his suit and tie are more vibrant than the hollow man inside them. All the symbols of what might sustain, entertain, and distract him crash through the splintered wood of his tomb-desk: a soup bowl, a picture frame, a drum kit, remote control, and clock. To add insult to injury, a surveillance camera makes public his private humiliation. The handcuffs that hang from his desk do not appear to be needed. Is the blood dripping from the filing cabinet his own, sapped by this office? And does his shadow betray a noose around his neck? The so-called settled citizen reminds one of Melville’s miniature masterpiece, “Bartleby the Scrivener,” an ode to the patron saint of civil servants, the dispirited automatons of an absurd workplace. In Eliot’s “Prufrock,” these are all who “measure out their lives in coffee spoons” in demoralizing circumstances, performing tedious tasks that they would prefer not to.

“You’ve been beaten, and it’s been deliberate. The whole society has decided to make you nothing. And they don’t even know they’re doing it,” another artist/activist spelled it out. That’s James Baldwin, laying his heart bare in a 1984 Paris Review interview. Baldwin is describing his desperate state of mind after his best friend jumped off a bridge in the US. “My luck was running out,” he elaborates. “I was going to go to jail, I was going to kill somebody or be killed.” With forty dollars in his pocket and a one-way ticket, Baldwin takes the sanity-restoring and life-saving leap to France.

As I write this appreciation of Walid Ebeid’s quietly devastating art, with the ten-year anniversary of our Egyptian revolution come and gone, I find myself meditating upon this small poem by Peter Meister:

Beloved homeland,

how did we let you steer us

so far away from Home?

I wonder, is Home the Egypt I grew up in, which I revisit with constricted breath in Ebeid’s occasionally claustrophobic work, or is it the embattled United States where I have been attempting to make a new life for the past decade and a half? Sometimes borders blur, colors bleed, and I’m not sure where I landed, as if the Egypt I fled trailed me―stealthy as a shadow, shapeshifting along the way. Plus ça change . . .

Ebeid’s hard-hitting work demonstrates how it is possible to be a lover and a fighter; perhaps—even necessary―when the beloved is slipping away, a lover becomes a fighter. Naji, too, and other art-ivists who fiercely critique their homelands recognize that nations can be like families: difficult to forgive from time to time but also impossible to abandon. If we hold them to a higher standard, demanding more of them, it’s because we know what they’re capable of, and it’s out of frustrated love that we remind them of their ideals.

Ebeid’s hard-hitting work demonstrates how it is possible to be a lover and a fighter.

Baldwin understood this exquisite tension and its price, profoundly: “I think that it is a spiritual disaster to pretend that one doesn’t love one’s country. You may disapprove of it, you may be forced to leave it, you may live your whole life as a battle, yet I don’t think you can escape it.”

In closing, permit me one final echo as well as a brief remembrance of a fallen hero, familiar with this tricky terrain of the heart. This Valentine’s Day, revered Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti passed away, joining his beloved wife, novelist Radwa Ashour. At the age of seventy-six, Barghouti, a poet of lifelong exile, was four years older than the state of Israel and wrote movingly about the twin sins of occupation and oppression. In his acclaimed autobiographical novel, I Saw Ramallah, the national treasure describes returning to his beloved Palestine, for the first time in three decades, this way:

The homeland does not leave the body until the last moment, the moment of death.

The fish,

Even in the fisherman’s net,

Still carries

The smell of the sea.

Ft. Lauderdale, Florida