Gouranga

“Gouranga has been diminished by fate,” writes Jitendra Nath Misra, “so let us give him a home.” In the following essay, the author celebrates the legacy and magic of this night drummer, “the sacred geographies of his body and mind.”

What would be the colour of our world without light? The default option of darkness offers new possibilities. With perpetual light, would we not seek the intimacy of darkness? Why blame darkness? This is the Indian curse, subverting our choices with that cheesy fair-and-lovely stuff. Cream it off, turn off the light, and answer the question. If light causes the polluting shadow of the low-caste person, is he to blame? Poor chemistry and unfair physics affront me. We see darkness as a firewall against wisdom and strength. It has to be light that works its way in. Jay Gatsby watching that green light across the bay with thoughts of Daisy in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby is a good story. But it is a story immersed in light, not darkness.

We see darkness as a firewall against wisdom and strength. It has to be light that works its way in.

Let us reconsider darkness. Let us agree that darkness and light exist in relation to one another. If you play with white in chess you get the advantage, but you can win with black. Just knowing this can make us play with the freedom of djinns singing on the dark side of the moon.

If the world were without light, there would be the possibility of seeing the beauty of darkness. Have you ever thought of the world according to a blind man? He can still see the good around him with the gift of a compensating perception. He stores his world in the far corners of his heart and mind. His craving for light actually helps him create situations where the darkness around him opens the way to light. This is the profundity of ordinariness. This could be dark stories, or the demons of mythology, or demons within, or a black ink stain on used paper, or a piece of white chalk on a black slate during a math lesson. Darkness, like light, is beauty that yields a new world.

It is no exaggeration to say that “dark” denotes impurity in some cultures. One type of darkness is the darkness of skin tone. This can take different forms in different cultures. What kind of humans are we that consider the shadow of fellow humans polluting? In the village of Haripur, humans considered refined are the ones with a lighter skin tone. The dark are objects of a hungry tyranny. Even the rice the two groups eat is different—the white arua is consumed by the upper castes, and the brown usuna by the others. Hardy labour is never enough to jolt misconceptions.

Once, Haripur had its patriarchs deploying their wits, squeezing tenants in their estates, bound to their respective duties by their colour. Morning was for the estate manager’s rounds of the homesteads of the tenants. After checking who would come for the day’s work, the manager did his sums in front of the patriarch. This was math as ritual.

Every tenant saying no received a reprimand from the Lord and Master: “How can that ungrateful scoundrel not show up even after taking so many advances?” The bemused manager hid his smirk, because the patriarch’s anger was sterile, without an innate quality, just show and pomp. Pantomime language never resolves the problem. Tenants had the freedom not to show up, and almost felt empowered by denying the landholders the right to deploy them as they saw fit. To be dark was to be defiant, and an opportunity according to time and place.

The coconut harvest season was the moment to drive a bargain. It came every quarter, and the fruit had to be picked on certain dates. This task was the Bauri community’s, which, over generations, had developed the specialised skills required to climb coconut palms. The dark-skinned Bauri knew a delay in the harvest would make the fruit bone-dry and unfit for consumption. So, they dragged the timelines and extracted as much as they could from the estate owner. The seasons have their own ways of sorting the battles between the light-skinned and the dark-skinned. The economics of the seasons can soften the hegemony of lighter skin.

A lot of patriarchal cajoling went into making the light-skinned have their way. This was based on an intricate system of patronage and incentives. Usually, the tenants fell for this game. They were smothered by doubt and the chain of heredity. There was considerable brainwashing on both sides. The twice-born Brahmins genuinely believed that knowledge and power were divinely ordained. The dark-skinned tenants sulked and thought of ways to hit back. They were far from being fatalistic, just lacking the tools to fix the problem.

Is it not comforting to the human race’s perennial search for dignity and equality that nature has its own way of imposing the sameness of experience on all of us?

In Haripur, with its mixture of privilege and destitution, its twice-born light-skinned Brahmins and lesser mortals, there was one thing that applied equally to all: darkness. During nights, when the jatra theatre was held, nobody objected when the Brahmin and the Shudra sat side by side, dissolving the caste lines. Darkness could not be farmed out, we could not bribe it, or get rid of it. Darkness was the great equalizer. Why theorise about Democracy, then? Is it not comforting to the human race’s perennial search for dignity and equality that nature has its own way of imposing the sameness of experience on all of us? Isn’t darkness the revenge of the poor against the rich?

Gouranga

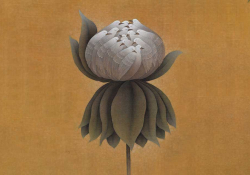

So, we come to the dark-skinned Gouranga, who forefathers this tale. Darkness never worked against him. Don’t owls operate better in the dark? Haripur came to life at night with rituals and light and festivities because nobody feared darkness. For Gouranga, darkness seemed the best thing to be. That is why Gouranga conjured some of his best magic as a drummer at night.

Gouranga was from the Pana community, a “victory in darkness” avatar. Excuse me if I exult. Gouranga was the super craftsman whose skills seemed preordained by some cosmic math. He knew his measurements, time, and space, when to begin, where to blockade fantasy. Gouranga was childlike. Adults feel muted by the impending feeling we are imperfect. Only the child is beyond himself because he has not yet learnt to demur. Gouranga was that kind of person, a man-child.

A dark-skinned man whining before his employer was not an option. You just move on, like water filling up spaces around it. Given his situation, fear might have stalked Gouranga every day of his life. But he was fearless. Gouranga had an alternate existence, a world of high skills that endowed him with uncommon power. He carried in his grasp the codes he used for his craft. This was his great secret and treasure, never to be shared. Gouranga is gone, but his children are bound to his oaths, because of ancient rituals for the departed.

Gouranga can never fade in the glare of the markets. His shelf-life is timeless. Gouranga was a hero to many children, the worker in their fathers’ estates, whose deft coal-black hands built objects of profound and durable beauty, and he was the musician who broke the boundaries of all rhythms and created hymns in the dark. Lest my praise get past the censors, please listen, just once more. Gouranga’s fingers tickled every form of coarseness there was, period.

Gouranga was better known as Goura, a cheery man whose black skin concealed a creative bloodline. When Goura smiled, his teeth glistened, and others might have been baffled at what they thought were his fluke skills. His parents gave him the name Gouranga (the one with the fair limbs) in symbolic denial of his skin tone, and his talent and karma did not count. Goura’s skills were masterly. He was not a specialist workman, but the best part was his dancer-drummer role during Dola Purnima. He would beat the drum and match the steps of the Naga dancer he was assigned to, as if they were warrior twins, protesting common violence by immersing in something sublime.

Gouranga would beat the drum and match the steps of the Naga dancer he was assigned to, as if they were warrior twins, protesting common violence by immersing in something sublime.

Goura and his mates became master performers at night, playing the drums they had made from hides, but never daring to cross the caste lines. The higher-caste Naga dancers had to be the winners in this artistic tug-of-war. Goura’s dreary toil of the day was compensated by his art at night. This was an equal balance, like the two themes of a symphony that seem like one. If the West mastered harmony and counterpoint, Goura’s organizing principles made him the wholesome human, able to create toil and grace all at once. Only, Goura could not translate his skills and energy to a higher level of self-awareness. Are we to be blamed for the fluky coitus of our parents?

Could Goura have done something else, like opening a shop? But the caste boundaries were so tight that this was unthinkable. The Brahmins of Haripur could of course do any kind of job, such as opening shops or rice-husking mills, as some did. But under the time-honoured organizing principles of production in the village, a Bauri harvested coconuts, the Gouda was a milkman, the community of fishermen was known by the word Keuta, the Pana created drums and leather products from the pelts of dead animals, and the Panda performed temple rituals. Each was a member of the chosen community, and nobody asked who had made this decision, as if the Universe had been created of segregated stars with their own cauldrons, each made of a different light.

It was the Brahmanical code of cajoling and control that mediated conflicts between castes and communities. In the way the Brahmin community looked at the service castes, their dark skin became Darkness, the hidden tyranny of privilege. Shadows were a shaming statement, when explained in the dubious morality of Brahmanical purity.

By 1998, Goura’s skin had become hidelike from being left behind by his caste lines, but his eyes still had their glint. Goura was waiting for an uncertain communion with the Lord. Even as an old man, Goura could still dance if asked to, and create a roof over the village hutments out of rice straw. There are millions like Goura, but we fail to appreciate their artistic demeanour because we are tricked into negative thoughts by anything dark, daunted by what we cannot see.

There are millions like Goura, but we fail to appreciate their artistic demeanour because we are tricked into negative thoughts by anything dark, daunted by what we cannot see.

Being poor and low in the social hierarchy matters more to the person living such a fate, who is swallowed by the goings-on, than a sympathetic observer, who seeks to understand the many facets of darkness. Goura was of course neither. He was the power of Darkness. Actually, this may be fantasy (just kidding). Since Goura has been long gone, his world is now difficult to decode. All I suggest is that he always wore his protective armour, and never complained about who he was. His altruistic art was unwavering and unaware. That was its lawful beauty.

Thus, this has to be Gouranga’s story, an exploration of the sacred geographies of his body and mind. Gouranga is not a commodity but a practitioner, with instruments that subdue colour. The alleys of Haripur have become pathways to interrogations. Gouranga becomes its hero because he fills me with shame and guilt, my throat clots in a lump, and I become the narrator to erase that blockage. Gouranga, I am sure, is now irreverent towards his name. He was the actual twice-born (each one of us has the potential to be a Gouranga, but leave that for another day). Gouranga has been diminished by fate, so let us give him a home. Gouranga’s caste lines never mattered and will never matter because he is the oracle (Gouranga will be reborn with blue veins as a great environmentalist). Gouranga is the artist who never dies alone, or lives alone, or fears alone, or thinks alone, or eats alone. Before his tale gets baggier, let Gouranga end it on his terms, making us Him.

New Delhi